What do we really mean when talking about student-staff partnership?

Daisy BAO*

Student-staff partnerships have gained considerable interest from researchers and educational developers in higher education in the last twenty years (academic studies: Nesheim et al., 2007; Healey et al., 2014; Bovill, 2019; praxis regarding HE quality: Higher Eduacation Academy, HEA, 2014; The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, QAA, 2018; AdvancedHE, 2021). Evoked by the nationwide interest, the conception of student-staff partnerships has been used in different areas of higher education, such as pedagogic improvement (Kupatadze, 2019), academics’ professional development (Jarvis et al., 2013; Marquis et al., 2018), subject-oriented research (Abbott et al., 2021), and curriculum design (Reeves et al., 2016). Through these means, the concept of student-staff partnerships has been developed across fields of curriculum, pedagogy, quality assurance, student learning, and even institutional administration. A broad range of fields using this concept has resulted in criticism regarding its uncritical adoption and conflation with ‘student engagement’ and ‘student voice’ (Rand, 2016; Tong, Standen & Sotiriou, 2018; Kehm, Huisman & Stensaker, 2019, pp. 343–354). The three key conceptualisations of student-staff partnerships are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Conceptions of student-staff partnership (SSP)

| Focus | Opinions | Scholars |

| SSP is a form of engagement | Student engagement consists of student partnerships, and student voice in co-producing the curriculum in the UK marketised universities | Carey (2013) |

| SSP is one type of student engagement, loaded by students and institutions with shared responsibilities | Trowler (2015) | |

| SSP is a result of engagement | Student engagement is student voice; SSP is a result of student engagement | HEA (2014)

QAA (2002) |

| SSP is a process of engaging students | SSP is an ideal approach to achieve student engagement, and a higher level in student engagement; | Healey et al. (2014) |

| Student engagement is categorised into different levels by what is being formed through student engagement, including understanding, curricular, and community; SSP is likely to happen at the pinnacle of student engagement | Kehm (2019) |

For instance, Carey (2013) encapsulated student-staff partnership and student voice within the concept of student engagement in his work on co-producing the curriculum in the UK marketised universities, which separated student-staff partnership and student voice as two independent elements. An antithetical definition of student-staff partnership made in the UK Engagement Survey (HEA, 2014, p. 13) stated that student voice constitutes student engagement, while partnerships were conceptualized to be the result of engagement. The HEA Engagement Survey (2014, p. 13) argued that in the UK context, student engagement encompassed not only ‘how students individually invest effort in their courses’, but ‘how students collectively influence the decisions that affect them’, namely student voice. The philosophy of focusing on partnerships is congruent with QAA (2012), which strived to achieve partnerships and centre students in higher education by involving undergraduates in their quality assurance Review Team.

There certainly are exceptions to neglecting the subtle distinctions between student engagement, voice, and partnership. Trowler (2015, pp. 306–307) argued that although ‘partnership’ was one type of engagement loaded by both students and institutions with shared responsibility, there is a tendency in both research and practice to simplistically reduce partnership to student involvement in decision-making processes, without taking into account their social and political positionalities and interests, such as race, gender, and social class. As a result, Trowler (2015) emphasised that chaos in conceptualising the student-staff partnership might lead to conflating the accountability of students and institutions , and to blurring the boundaries of student engagement and student partnership in curriculum design. Healey et al. (2014, pp. 15–17) believed that student-staff partnership was an important approach to achieving student engagement; they argued, based on their long-term research experiences on student engagement since the 2000s, that ‘all partnership is student engagement, but not all student engagement is partnership’. They, as figure 1 shows, encapsulated research partnership (defined in terms of subject-based research and inquiry and the scholarship of teaching and learning) and partnership in learning and teaching (defined in terms of learning, teaching and assessment, curriculum design and pedagogic consultancy) within student-staff partnership terminology.

Figure 1 Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education model, developed by Healey et al. (2016, pp. 24-25)

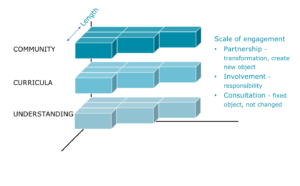

Figure 2 Nested hierarchy of the strategy of student engagement (Kehm, 2019)

In addition to Healey et al.’s approach (2016), in which partnership is conceptualised as a form of engagement at the highest level, Kehm (2019) built a hierarchy model for student engagement, in which partnership is viewed as the ‘pinnacle stage’ in a scale of various engagements (see figure 2). Rather than engagement in ‘a wide range of teaching and learning process’, as stated in Healey et al.’s model (2014), Kehm (2019) defined student engagement as regarding ‘what is being formed through engagement’, including ‘understanding’ development, ‘curriculum’, and learning ‘community’. In this model, engagement to form communities builds on developments of curricula and understanding. Meanwhile, engagement to develop curricula is based on engagement to improve understanding. By identifying what activity is engaged in and what depth of engagement is achieved, these three areas of Kehm’s (2019) model may reveal a more nuanced approach to teasing out and conceptualising the depth and multi-layered-ness of participation in student-staff partnership.

Theoretical research, as the one presented above, concerned with defining and/or conceptualising the student-staff partnership is scarce in the field of higher education studies. The practical conceptions held by students, staff, and educational developers in praxis also remain under-researched (Maunder, 2021). We need to be sceptical about whether student-staff partnership practices and policies are congruent with what they claim to achieve, namely a collaborative, reciprocal process in teaching and learning (Bovill et al., 2014).

References

Abbott, L., Andes, A., Pattani, A., Mabrouk, P. A. (2021). An Authorship Partnership with Undergraduates Studying Authorship in Undergraduate Research Experiences. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education, 32 (2021). https://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss32/2

AdvancedHE. (2021). UK Engagement survey 2021. AdvancedHE. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/advance-he/AdvHE_UKES_2021_1636545587.pdf

Bovill, C. (2019). Student–staff partnerships in learning and teaching: An overview of current practice and discourse. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 43(4), 385-398.

Carey, P. (2013). Student as co-producer in a marketised higher education system: a case study of students’ experience of participation in curriculum design. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50(3), 250–260.

Cook-Sather, Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning

and teaching a guide for faculty (First edition.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass,.

Healey, M., Flint, A., Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement through partnership: students as partners in learning and teaching in Higher Education. York, UK: Higher Education Academy.

Higher Eduacation Academy (HEA). (2014). UK Engagement Survey 2014: The second pilot year. Higher Eduacation Academy. https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/59374/1/Buckley_HEA_2014_UK_Engagement_Survey.pdf

Jarvis, J., Dickerson, C. & Stockwell, L. (2013). Staff-student partnership in practice in higher education: The impact on learning and teaching. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 90(2013), 220-225. in 6th International Conference on University Learning and Teaching (InCULT 2012), Malaysia, 20/11/12.

Kehm, B. M., Huisman, J. & Stensaker, B. (2019). The European Higher Education Area. London/New York: Springer International Publishing.

Kupatadze, K. (2019). Opportunities presented by the forced occupation of liminal space: Under-represented faculty experiences and perspectives. The international journal for academic development, 3(1), 22-33.

Maunder, R. E. (2021). Staff and student experiences of working together on. pedagogic research projects: partnerships in practice. Higher Education Research and Development, 40(6), 1205-01219.

Nesheim, B. E., Guentzel, M. J., Kellogg, A. H., McDonald, W. M., Wells, C. A.; Whitt, E. J. (2007). Journal of College Student Development, 48(4), 435-454.

Rand, R. (2016). Researching undergraduate social science research. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(7), 773-789.

Reeves, N. L. Barral, A. M., Sharif, K. A., Wolyniak, M. J., Leung, W., Shaffer, C. D., Lopatto, D., Elgin, S. C. (2016). The Genomics Education Partnership: Assessing and Improving a Course‐based Undergraduate Research Experience (CURE). The FASEB Journal, 30(S1), lb197-lb197. https://faseb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1096/fasebj.30.1_supplement.lb197

The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA, on behalf of the UK Standing Committee for Quality Assessment, UKSCQA). (2018). The revised UK Quality Code for Higher Education. UKSCQA & QAA. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/quality-code

The Quality Assurance Agency (QAA). (2002). A Map of the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area to the UK Quality Code for Higher Education. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/quality-code

Tong, V. C. H., Standen, A. & Sotiriou, M. (2018). Shaping Higher Education with Students. London: UCL Press.

Trowler, V. (2015). Negotiating Contestations and ‘Chaotic Conceptions’: Engaging ‘Non-Traditional’ Students in Higher Education. Higher Education Quarterly, 69(3), 295-310.

*Daisy Bao is PhD candidate at Moray House School of Education and Sport, The University of Edinburgh

Recent comments