Narratives and Fictions in Educational Research

Short stories as a research method?

To some of you, it may seem a curious choice that I write short stories as part of this research project. How can this be a scientific method?, you might be wondering.

Since the 17th century, writing has traditionally been divided into either literary or scientific, but then over the course of the 20th century the lines between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ started to be blurred, and by the 1970s, combinations like ‘creative non-fiction’, ‘faction’ or ‘true fiction’ emerged.1 Since then, postmodernist researchers have made a convincing case for writing as a method of inquiry in qualitative research2. Among them is Peter Clough, whose work focuses on narratives and fictions specifically in education research3. My work with the short stories draws heavily on his thoughts and examples, so let’s consider some questions about epistemology, the role of researchers and advantages of narratives and fictions as a research method.

A fundamental purpose of this research project (and of most research projects, you might agree), is to produce knowledge. There are many possible ways for doing this: Collecting data, presenting graphs or conducting an experiment are some conventional examples. Writing a fictionalized narrative is a way “to produce different knowledge, and to produce knowledge differently”4. Think about, for example, a survey-based research project. Data might be gathered through a questionnaire, and the answers are analyzed and interpreted by the researcher. In contrast to this type of research, narratives and fictions as a methodology have the power of “evoking the experience […] rather than explaining it”5.

A fundamental purpose of this research project (and of most research projects, you might agree), is to produce knowledge. There are many possible ways for doing this: Collecting data, presenting graphs or conducting an experiment are some conventional examples. Writing a fictionalized narrative is a way “to produce different knowledge, and to produce knowledge differently”4. Think about, for example, a survey-based research project. Data might be gathered through a questionnaire, and the answers are analyzed and interpreted by the researcher. In contrast to this type of research, narratives and fictions as a methodology have the power of “evoking the experience […] rather than explaining it”5.

This power is one of the reasons why I chose to write short stories from the data I gathered through interviews. The main purpose of the narratives about Eva and Maya in this project is to evoke an emotional understanding of the issue based on experiencing a reaction to the stories. This feeling is the type of knowledge I mainly set out to produce with this part of the project.

Of course, writing as a qualitative research method comes with its own set of challenges. There is more freedom to experiment with different textual forms and present it to diverse audiences, but Laurel Richardson in her postmodern take on stories as a method of inquiry reminds us: “The work is harder. The guarantees are fewer. There is a lot more for us to think about.”6

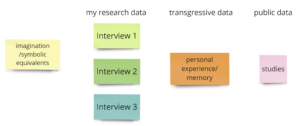

For example, since I am the writer of the stories, my own perspectives and impressions are inseparable from the narratives7. Researcher Elizabeth St. Pierre gives this problem a name: transgressive data. In her categorizations, this includes for example emotional or sensual data, but also dream and response data — in short: data that are usually not taken into account in qualitative research methodology8. With this consideration, I recognize and accept that my experience plays a role in how I report the experience of others. I am consciously blurring the lines between myself as the researcher and my interview participants as research subjects.

since I am the writer of the stories, my own perspectives and impressions are inseparable from the narratives7. Researcher Elizabeth St. Pierre gives this problem a name: transgressive data. In her categorizations, this includes for example emotional or sensual data, but also dream and response data — in short: data that are usually not taken into account in qualitative research methodology8. With this consideration, I recognize and accept that my experience plays a role in how I report the experience of others. I am consciously blurring the lines between myself as the researcher and my interview participants as research subjects.

At first glance it seems then that the short stories aren’t objective, ‘as research should be’; but if we think more closely about other types of research, it becomes clear that the researcher always occupies a certain position that influences their research. For example, in our Analysis of statistics on representation in physics, we see that the supposedly objective science of numbers and graphs can tell very different stories depending on the researcher’s choices in, for example, scaling the axis. In narratives, we are self-conscious about claims to authority, validity or reliability, and self-reflective about agendas hidden in the writing9.

Perhaps the most obvious reason for fictionalizing the student/teacher interviews is the protection of their identity. Stories, Clough writes, “can provide a means by which those truths, which cannot be otherwise told, are uncovered”9. In our case, the individual experiences of teachers and students — learners in their teenage years or young adults — are too personal, too sensitive to be shared directly with a public audience. The approach of telling their stories as versions of the truth provides “the protection of anonymity to the research participants without stripping away the rawness of real happenings”10.

This brings us to the next question that many of you might have:

How much ‘truth’ is in the stories?

This is a very complicated question without a simple answer since it heavily depends on your understanding of what is ‘true’. I can explain how these stories were constructed, and leave the ultimate judgement up to you.

In a nutshell, Clough’s description of his own stories also perfectly sums up mine11:

Though none of the stories happened precisely as told, they are all made from events which are real enough; made with the data of interview, life-historical fiction, observational and other inquiry; enriched with transgressive data from my own experience; and ‘knit with symbolic equivalents’ which maintain the reality while concealing the identity of actual people.

The process started with conducting three in-depth interviews, two with female undergraduate students and one with a female high school teacher of physics. They told me personal stories — anecdotes in high school classrooms, reflections about their choices, behaviors and emotions, interactions with instructors or peers, and other stories of their past and present experiences with physics education.

With this wealth of data, the creative process of crafting narratives began. I took a step back from the details of the transcripts and, from a bird’s eye perspective, tried to find the core of a story that could be told form their anecdotes. This comes back to Clough’s metaphor of the architect, where the primary question is not technical (‘How do I construct this building?’) but rather ‘what is it for?’ and ‘what must it do?’10. So I formulated this core,

- for Maya as:

the unlevel playing field: high school girls don’t have the same opportunities as boys to develop a physics identity – and when they do, it is socially sanctioned

- for Eva as:

how it feels when failure is expected and success unrecognized

Whether I succeeded in constructing a narrative that transmits this core to you as recipients is an entirely different question; perhaps you find different meaning in the stories, and that is equally valid.

With this clarity on the core of the story, I could now move on to puzzling the various pieces of data into coherent narratives. Each “unit of meaning”12, for example an event or a character, comes from one or more of the following four sources13:

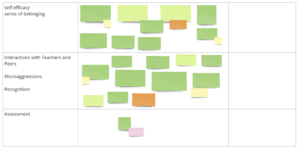

Here’s a visual overview of how this puzzling of sources looked like for constructing the two narratives:

| Maya | Eva | |

|

|

Let me illustrate this with just a few examples:

| Unit of Meaning | Source | Description

|

||||

| Character

Eva |

Interview 1 and 2 with undergraduate students |

Eva combines personality traits, details and anecdotes from two interviewees

|

||||

| Character

Sarah |

Interview 2 and 3 with undergraduate student and high school teacher

Study: Kessels, 200514 |

The high school teacher in my interview described in very general terms a student like the character Sarah in her class; this rough description overlapped largely with the high school memories of the undergraduate student I had interviewed before, so Sarah emerged as a character from this reported student experience, the teacher description and research findings from the study

|

||||

| Event

Christina laughing during the test and declaring herself a lost cause |

Interview 3 with high school teacher

Symbolic equivalents |

Anecdote from high school teacher; the conversation after class between Maya and Christina is a symbolic equivalent for a different context of Christina voicing her low self-efficacy beliefs

|

||||

| Event

Eva being the only one to solve the hardest problem |

Interview 2 with undergraduate student

Symbolic equivalents |

The main plot of the story Eva unfolds based on this anecdote from one of the interviewees; the context and details were changed to symbolic equivalents, for example the problem was not in quantum mechanics

|

||||

| Setting

Me attending Maya’s class for two weeks as an observer |

Imagination, inspired by article: McCullough, 200715 |

I did not spend time observing any interviewee’s teaching practice. I placed myself in the narrative to recount the happenings from this observer perspective. Researcher McCollough recommends that physics teachers arrange to be observed to find out if they’re paying more attention to specific groups in a class. This was the inspiration for the fictional set up in my story.

|

At this point you can see how tricky it is to determine how much of the two narratives is ‘true’. Perhaps you can also see that for the purposes of the stories, the question of the exact amount of ‘truth’ in the narratives is, at best, secondary.

Their main purpose is “to produce different knowledge, and to produce knowledge differently”4.

1Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 959–978). Sage Publications.

2 Note the indeterminate article here: “a method of inquiry”, meaning one of many. The whole point of this postmodernist thinking and approach to research is that “[n]o method has a privileged status” (Richardson & St. Pierre, 2005, p. 961). There is no implication that all qualitative research should be stories and fictions, simply that it is no more or less suitable than other methods.

3 Clough, P. (2002). Narratives And Fictions In Educational Research (1st edition). Open University Press.

4 St. Pierre, E. A. (1997). Methodology in the Fold and the Irruption of Transgressive Data. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 10(2), p. 175.

5 Clough, 2002, p. 73.

6 Richardson, L. (1994). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (1st ed., pp. 516–529). Sage Publications, p. 523.

7 This is why I introduce myself and tell you more about my background in the About Me section.

8 St. Pierre, 1997.

9 Richardson, 1994.

10 Clough, 2002, p. 8.

11 Clough, 2002, p. 79.

12 Clough, 2002, p. 72.

13 The category of ‘symbolic equivalents’ is an idea introduced by Dr. Irvin Yalom in his own stories about psychotherapy patients: Yalom, I. D. (1991). Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy. Penguin.

14 Kessels, U. (2005). Fitting into the stereotype: How gender-stereotyped perceptions of prototypic peers relate to liking for school subjects. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 20(3), 309–323.

15 McCullough, L. (2007). Gender in the Physics Classroom. The Physics Teacher, 45, p. 171-172.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.