Futures and Foresight

A very brief introduction to Futures Studies

The academic field of Futures Studies provides the framework and theoretical foundation for the third part of this project, Visions.

Scene from WALL-E: In their futures scenario, humans live in a space ship while robot WALL-E cleans up the earth. Stanton, A. (Director). (2008). WALL-E [Film]. Walt Disney Home Entertainment. |

When you hear the term ‘Futures Studies’, it may at first sound dubious. Perhaps you’re thinking of Sci-Fi movies, flying cars or robots like WALL-E in Disney’s movie painting a picture of humanity 800 years into the future.

How can we study the future? Isn’t this the realm of fantasy rather than research?

In an academic sense, Futures Studies can be described as “the systematic study of alternative futures to understand what could be and how we as humans might orient our actions in the present towards our preferred futures”1. There is an important implication in this definition: Futures studies is not simply about predicting what will happen, but rather about mapping alternative futures and making our desired futures happen2.

Future studies is based on some key assumptions about the future. There are a few competing theories by different futures scholars, but for our purposes in this project, let’s think about the following two principles as foundational3:

1. The future is not predetermined.2

2. The future cannot be predicted, but alternative futures can be forecasted and preferable futures can be envisioned.4

The first assumption is critical, because this means that future outcomes can be influenced by our actions. If the future were predetermined, it would just be a matter of finding more information to ‘know’ the future. With this assumption of non-determinacy, the second premise becomes clear: Since the future is not set in stone, we cannot ‘predict’ it; instead, we can think about an infinite array of alternative futures and imagine those futures that are desired (although which futures are ‘desired’ depends on who’s doing the desiring).

This activity of actively envisioning futures is called “futuring”1 — and this is precisely what we move to do for physics education in Visions.

Voros’ foresight process framework

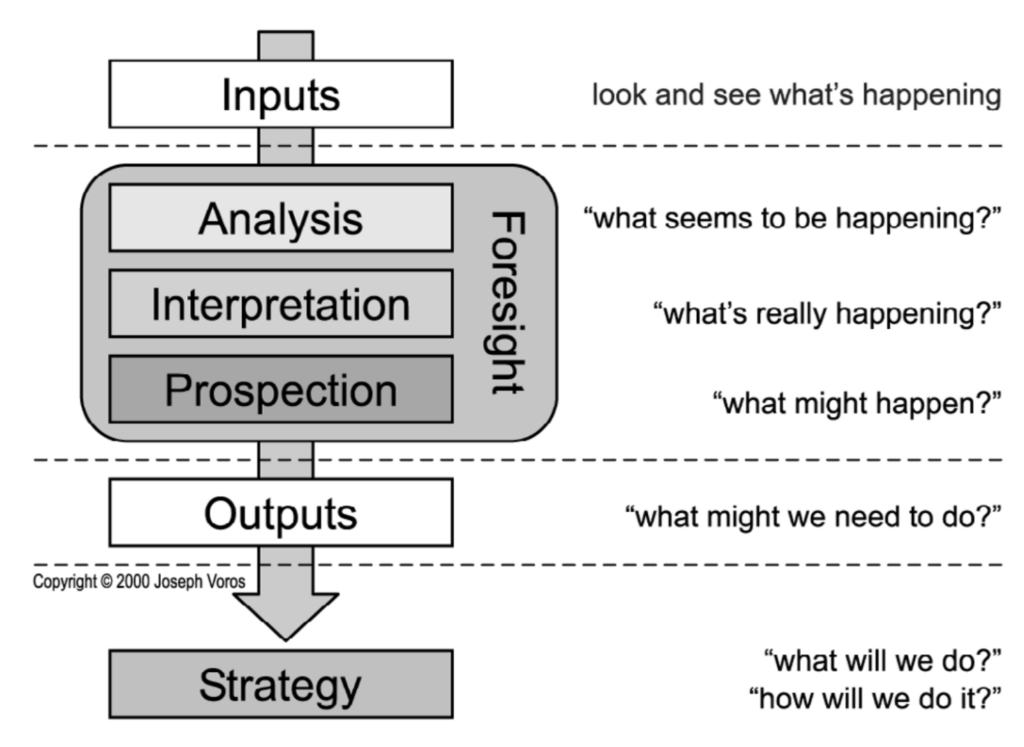

Australian futurist Joseph Voros helps us in this exercise with a widely cited and accepted framework he developed based on prior work of other futures scholars like Richard Slaughter5. Fundamentally, this process is divided into four phases, each of which is associated with different questions and potential methods.6

Let’s clarify what each of these phases do and how we apply this framework to physics education.

1. Inputs

This step involves the gathering of information. Voros is referring to futures information here: He lists for example strategic intelligence scanning and brainstorming ideas about the near future by experts as potential methods.

In our application, this step is more rooted in the present and starts with an in-depth literature review in the first part of this project.

2.a) Analysis

The goal at this stage is to “create some order out of the bewildering variety of data”7 that was obtained in the input stage. For our purposes: The research information in the analysis mind map are clustered into the categories of representation, learners, teachers, curricula and cultural narratives.

2.b) Interpretation

For Voros, this stage is about looking deeper at insights from the analysis stage and searching for underlying systems and structures. In the mind map, the isolated pieces of the various categories are tied together in the central visualization to find those deeper connections between the topics; additionally, the podcast episodes highlight the complex interplay of the factors exemplified in individual stories. The Recap section provides a summary of the steps until this point.

An important difference between Voros’ descriptions and our application of the framework is the question of where the ‘futuring’ starts. For Voros, the contents of all these phases are directed at futures, whereas we start with a thorough understanding of the present; our input, analysis and interpretation are centered around contemporary aspects and current trends in physics education. It is only in the next phase that we explicitly start looking into the future.

2.c) Prospection

To paraphrase Voros himself, if you have never heard this word before, it is because he invented this term to describe “the activity of purposefully looking forward to create forward views”7. This step is now where various alternatives of futures are explicitly created, and where Voros’ typology for different kinds of futures comes into play. We are doing precisely this prospection through a collaborative, asynchronous online activity in the corresponding section on this website, which is also where I give a brief video introduction to the types of futures and Voros’ visualization of the Cone of Futures.

3. Output

Voros describes this phase as two-fold, one is tangible and the other is intangible. The first may be some written or visual output of the range of options produced through the previous activities. The latter, however, is the more important form of output for him: The changes in thinking that are brought about by the whole process, especially by the creation of forward views in the Prospection step. The general goal is to get across the insights, preceding the next step of more formalized strategy work. For this project, I provide suggestions and ideas for types of tangible output, but echo Voros’ distinction between tangible and intangible outputs, emphasizing the second.

4. Strategy

This last step comes after the foresight work has been concluded, and involves familiar methods like strategy development and strategic planning. This is not the focus for Voros’ futures work, and neither is it for our project since at this point the developed futures scenarios have likely diverged based on different contexts and perspectives, so much so that I cannot provide meaningful input for how to strategize steps towards them.

A note about futures methods

Futures studies make use of a wonderfully diverse toolkit of methods and for interested readers I can recommend the European Foresight Platform for further reading8.

However, for this project, I faced some specific challenges in choosing a suitable method for our prospection:

- Diversity of Contexts: This website is designed for a broad academic and non-academic audience that may range from teachers to students, parents, activists, policy makers or researchers from different countries.

- Format: Since this project lives as a web-based platform, any activity should be implemented in an easily accessible online space

- (A)synchronism: You as readers of the website, that is, potential participants for an activity, are most likely interacting in an asynchronous fashion — or, depending on your context, you may be able to bring it into your institutional setting and work synchronously with your colleagues/peers/friends/etc.

Many of the methods traditionally used in Futures Studies are meant for fairly homogenous groups of participants interacting synchronously and, most likely, in person; For example, the method of the World Café would work wonderfully in a workshop setting where people can engage in conversation and travel from table to table9. Given the constraints of this specific project, I had to become more creative and ultimately developed the exercise by merging different methods.

- Our prospection activity is somewhat based on the Delphi method, but unlike its traditional application as a systematic way to gather input from experts10, I use the question format as creative, open prompts for you to apply to your contexts and develop your own visions.

- I encourage you to come up with ideas, even wild ones, in a brainstorming fashion — after all, Dator’s Second Law of Futures Studies states that any useful idea about the future should seem ridiculous at first4. This also brings in the method of Wildcards11, which Voros has also underlined as particularly useful for Prospection12.

- Then, as output, you are prompted to develop scenarios from your ideas, although in a much more open and creative way than the systematic, rigorous scenario method usually encompasses. The focus here is, as mentioned above, more on the intangible outputs, which is why the “decision-making utility”13 of your scenario is less important in this activity.

As we established in the Theory tab on the Female Gaze, the three parts of this project are all about stories: Finding them in the literature of the past and present, telling them through individual experiences, and creating new stories for futures of physics education. Well, now it comes full circle — the theory of the female gaze, the fictionalized narratives and the foresight work, all neatly tied together in a quote by Wendell Bell14:

The end product of all the methods of futures research is basically the same: […] a story about the future, usually including a story about the past and present

1 Anthoni, E., Leemput, M. V., Schoffelen, J., & Hannes, K. (2020). Futures Studies. In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, & R. Williams (Eds.), Sage Research Methods Foundations. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036949493, p. 2.

2 Bell, W. (1996). Foundations of futures studies: History, purposes, and knowledge. (Vol. 1). Transaction Publishers.

3 Note that these two are ‘cherry-picked’ by me in an attempt to break the complexity down to the most important parts specifically for our project. The first is one of nine key assumptions by Wendell Bell, the second I took from James Dator’s ‘Three Laws’ (see footnotes 2 and 4). A different formulation is given for example by Australian futurist Richard Slaughter (2004) with his five basic philosophical assumptions.

The two principles I picked out as foundational for our foresight work here are generally not controversial, but by no means exhaustive or complete — they have been formulated in many different ways, with other additions or specifications.

Here are some references for further reading, in addition to Bell and Dator:

-

- Sardar, Z. (2013). Future: All That Matters. Hachette UK.

- Slaughter, R. (2004). Futures Beyond Dystopia: Creating Social Foresight. Psychology Press.

4 Dator, J. (1998). Introduction: The Future Lies Behind! Thirty Years of Teaching Futures Studies. American Behavioral Scientist, 42(3), 298–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764298042003002

5 Voros, J. (2003). A generic foresight process framework. Foresight, 5(3), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636680310698379, p. 14.

6 … and again this is by far not the only option! For example, Sohail Inayatullah (2003) offers an alternative generic framework of Six Pillars that is similar to Voros’ process framework in its step-by-step approach associating different methods with different stages. I chose to follow Voros’ suggestion for our foresight work because of the tangible nature of the questions he provides to summarize each stage, as well as his popular, clear visualization of the Cones of Futures.

However, if you want learn more about Inayatullah’s approach, check out his paper: Inayatullah, S. (2003). Futures at Tamkang University. Futures, 35, 1075–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(03)00073-9

7 Voros, 2003, p. 15.

8How to do Foresight? – European Foresight Platform. (n.d.). Retrieved May 20, 2024, from http://foresight-platform.eu/community/forlearn/how-to-do-foresight/

9 World Café – European Foresight Platform. (n.d.). Retrieved May 20, 2024, from http://foresight-platform.eu/community/forlearn/how-to-do-foresight/methods/creative-methods/world-cafe/

10see, for example, Renzi, A. B., & Freitas, S. (2015). The Delphi Method for Future Scenarios Construction. Procedia Manufacturing, 3, 5785–5791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.826

11 Petersen, J. L. (1999). Out of the Blue: How to Anticipate Big Future Surprises. Madison Books.

12 Voros, 2003, p. 17.

13 Scenario Method – European Foresight Platform. (n.d.). Retrieved May 20, 2024, from http://foresight-platform.eu/community/forlearn/how-to-do-foresight/methods/scenario/

14 Bell, 1996, p. 317.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.