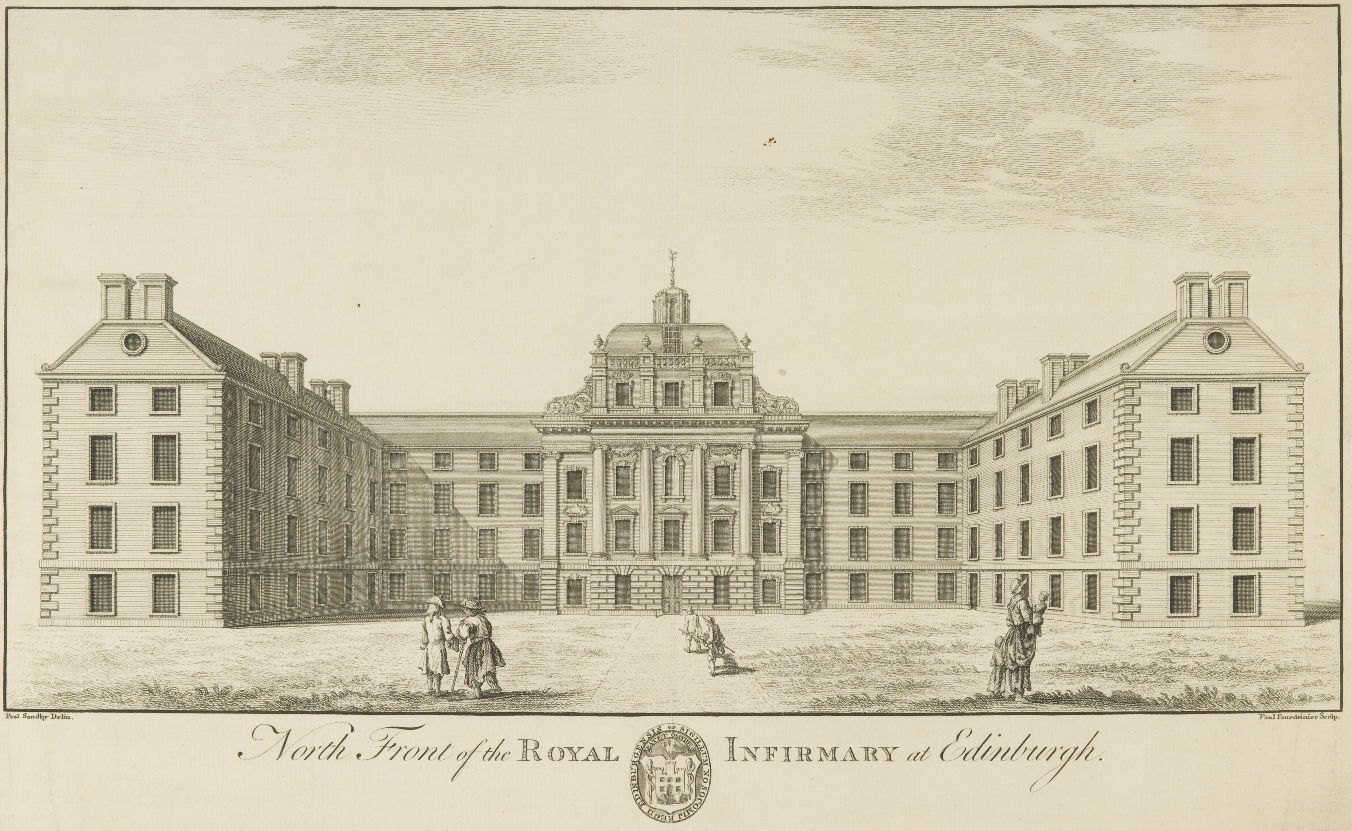

Medical education in Edinburgh 1700-1850

In the 21st century you need to demonstrate competence and pass the relevant examinations to graduate with an MBChB degree and practise medicine (Philips, 2020). However until the end of the 19th century university trained doctors made up a tiny fraction of medical practitioners. The majority of health care, particularly in rural areas, was by provided by lay practitioners (Bonner, 1996). They learned by apprenticeship and generally had a speciality such as bone-setting or midwifery, and were able to use their personal experience to manage straightforward cases. However their knowledge was limited (Clarke, 1966). The scientific revolution that exploded in the 18th century brought a deeper understanding of physiology, and a widening gap formed between the apprenticed practitioners, and seeing a qualified practitioner. Of those who did receive qualifications, the profession was fragmented into three, mostly opposing, groups: barber-surgeons, apothecaries and physicians (Bonner, 1996).

Barber-surgeons practised bloodletting, drawing teeth, and surgery. Their training was highly practical, and consisted of 5 year indentured apprenticeships under a master surgeon. In Edinburgh they were examined and licensed under the Royal College of Surgeons, who by the 1505 Seal of the Clause had exclusive privileges over anyone practising surgery in Edinburgh and the surrounding districts (MacLaren, 2005).

Apothecaries also learned by apprenticeship. They had a role similar to modern day general practitioners (GPs) diagnosing conditions, giving medical advice and dispensing suitable medications (Simmons, 2019).

Physicians tended to have a highly academic background. Initially only Oxford and Cambridge offered medial degrees. The course was long; focused primarily on studying classical literature and ancient Greek medical texts ; it had no practical component, though with time an increasing number of students elected to supplement their studies with an apprenticeship (Bonner, 1996).

Scottish qualifications, particularly at Edinburgh, became a popular choice for aspiring physicians. They required only 3 years of study, and offered a more practical approach by (uniquely for the UK) integrating clinical work into their course. Edinburgh also provided a wider range of medical courses, including surgery, whilst also incorporating the new disciplines of chemistry and botany. Teaching was carried out in English, not Latin, and students were not required to have studied Latin or Greek prior to admission (although these subjects became recommended for admission in 1824), expanding the range of students that could attend. Furthermore, a number of needy Scottish students were admitted to lectures for free, further breaking down the rigid division of social classes in medicine. Most did not graduate (only one in every five students who took courses in Edinburgh between 1765 and 1825 graduated!) as university lectures were seen as a supplement rather than a requirement for practising medicine. For the most part, medical students created their own medical degree through a combination of apprenticeships, “walking the wards” of a hospital, and attending courses offered by private “extramural” schools (Bonner, 1996).

By the end of the 18th century each class of practitioner had a well defined role, and fought to maintain the artificial boundaries they had set up. Medical knowledge was not always shared between groups, and often patients’ conditions did not fit neatly into the somewhat arbitrary domains. So most practitioners also carried out some form of general practice as well (Clarke, 1966). It became clear that radical reform was needed in order to create a safe system for patients (Dingwall, 2010).

This consolidation and standardisation of medical education began in earnest with the Apothecary Act of 1815, which introduced a compulsory 5 year apprenticeship and required a Licence of the Society of Apothecaries in order to be able to dispense medicine. However the quality of education and apprenticeships varied wildly. Those who had carried out an apothecary shop apprenticeship held the same freedoms to practice as someone holding a degree in medicine from Oxbridge.

The Medical Act of 1858 established the General Medical Council. Their role was to establish and maintain an up to date a register of medical practitioners (published annually), decide which qualifications were registerable, and to supervise examinations. They maintain these roles to this day (Bonner, 1996). The act also abolished geographical restrictions on practice. This would become particularly important for foreign students in the era of colonialism, as it granted them the authority to practise throughout the Commonwealth (Dingwall, 2010).

Author: Tanith Bain, July 2021

References and further reading

Tanith Bain’s post on The Edinburgh Triple follows this one.

The featured image shows the new, second Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, built in Infirmary Street. It opened in; this drawing is by Pierre Fourdrinnier in 1751, from University of Edinburgh Collections accession number EU4371.

- Bonner TN, 1996. Becoming a physician: medical education in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, 1750-1945. JHU Press.

- Clarke, E., 1966. History of British medical education. Medical Education, 1(1), pp.7-15.

- Dingwall HM, 2010. The Triple Qualification examination of the Scottish medical and surgical colleges, 1884-1993. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 40:269-276.

- MacLaren I, 2005. A Brief History of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Res Medica, 268:55-56.

- Simmons A, 2019. Trade, knowledge and networks: the activities of the Society of Apothecaries and its members in London, c. 1670–c. 1800. The British Journal for the History of Science, 52:273-296.

(Pierre Fourdrinnier 1751, from University of Edinburgh Collections accession number EU4371)

(Pierre Fourdrinnier 1751, from University of Edinburgh Collections accession number EU4371)

Recent comments