“The embodied inner being that is more than memory, and that exists within us all”

Our first INCLUDED Project workshop in late May, which Frankie wrote about here, left us all brimming with excitement and enthusiasm for where the project might lead us next. It was therefore with considerable anticipation that we met for our second workshop at the end of June in Edinburgh.

The first workshop had focused on ethics, and the main takeaway of the day for me was the group’s consensus that we must consider the inclusion of people living with advanced dementia as active and equal participants in research into their lives and experiences to be an ethical imperative. One of the clear obstacles to this which the group—which consisted of a mixture of academic researchers, like myself, people living with dementia, people who work with people living with dementia, and people with artistic and creative practices which focus on dementia—identified was the existing structure of academic ethics systems.

These systems are predicated on what is considered to be the competency and ability to give and affirm informed consent, something we all agreed was a very important principle, but which lacks the flexibility in its implementation to be open to many people who live with advanced dementia. This system currently serves to disbar a considerable number of people from being competent, meaning that their views and knowledge are absent from the research into their lives. This, we all agreed, is itself unethical. The unanimity in the room around this understanding, and a shared determination to find ways rethink how such research is done, provided all the energy and motivation we needed to propel us into our second workshop.

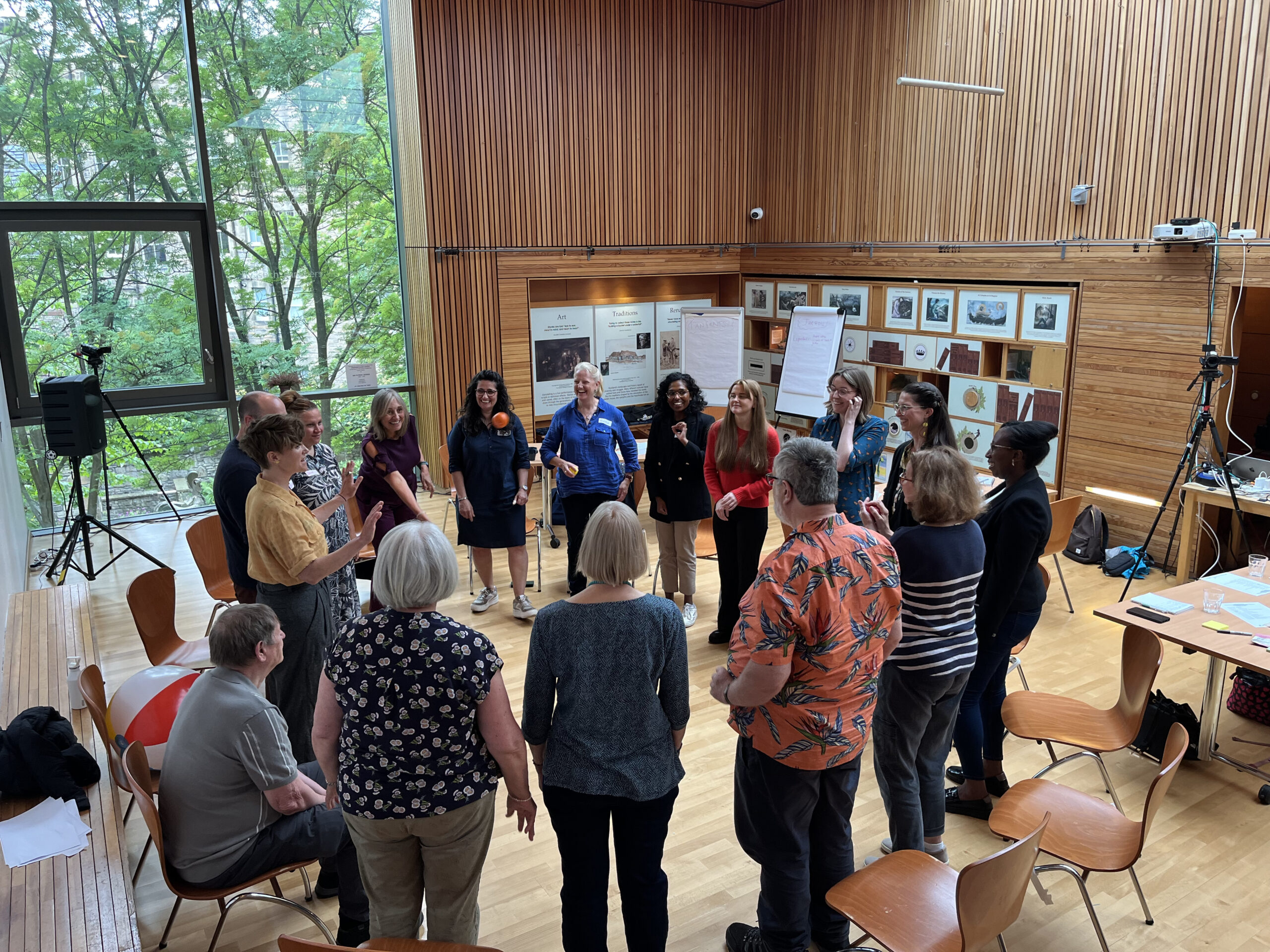

We therefore gathered our diverse group again on the 30th June with both an online group and an in-person group, who met in the lovely Storytelling Court room of the Scottish Storytelling Centre.

Our central theme was to consider together the vital question of how to think beyond the most common methods we use in social research, for example the multitude of varieties of interviews and surveys. These overwhelmingly rely on words, whether spoken or written, and whilst very effective for conducting research with many people, exclude those for whom words are not the best way to express themselves.

People living with the more advanced stages of dementia are amongst those for whom this often applies, and this is one reason why they are often considered to be incapable of participating fully in research. Just as we found with ethics systems, people living with advanced dementia are too often considered to be the problem in this sense, and as ‘they’ don’t fit into the ways of working that academic researchers are used to. This then means that they are overwhelmingly excluded. What we gathered to do then was to explore ways to change the system, to explore ways of doing research otherwise, and do so by considering the use of artistic and creative methods and practices.

To help us do this we invited two artistic practitioners to speak to us about their work, and to lead practical sessions through which they shared some of their insights from their many years regularly working with people living with dementia.

Suzie Ferguson spoke first about her work as a ‘therapeutic clown’ in the Elderflowers programme of the Hearts and Minds charity, which specialises in using the theatrical practice of clowning to work with people living with dementia. Suzie described for us how she and her colleagues have used clowning as a means to spark meaningful communication with people for whom verbal communication may not be the most effective means of communication. They work improvisationally, with the performances and interactions co-produced with the people they regularly meet, and achieve levels of shared understanding, of co-produced knowledge, that we academic researchers should be envious of.

Suzie Ferguson presenting in the Storytelling Court room of the Scottish Storytelling Centre

I was instantly struck by the clowns’ ability to form connections with people who would generally be considered incapable of participating in academic social research, as usually conceived. In the stories she told us there were many lessons that we would do well to take on as we develop the research programme that we hope emerges from our workshops. I will concentrate on a couple that felt to me to be particularly important.

Speaking of the people that she and her colleagues visit regularly she told us that:

“the people we meet know exactly what they need, to feel more in control, to have the opportunity to help others, to be touched with tenderness, to be seen and heard, and to be celebrated, for who they are.”

There could scarcely be a better checklist for a social researcher when considering the viability and importance of selecting research participants and collaborators. The brief short-term engagements that the current research paradigm tends to compel us towards however mean that it is incredibly difficult for researchers to come to this kind of deep understanding. To form the kinds of relationships and modes of communication with those living with advanced dementia which make possible such understandings of their worlds requires the consistent and long term engagement that Suzie and her fellow clowns commit to.

The mode of engagement, the spirit with which they engage with people, is a vital component of their process. Their

“intention is only to connect with that part of the person that lies beneath cognition, the embodied inner being that is more than memory, and that exists within us all”.

They do not engage with people as ‘people living with dementia’, but holistically as people, who are as fully human as any other. She described how through this process they bring together the worlds of the clowns and their interlocutors, creating together a new world, a shared world within which they dwell for the duration of their encounter. For a researcher this would require great humility, a willingness to move away from pre-determined research plans and questions, and a deeply reflexive and embodied research practice. Suzie described this process as requiring

“presence, deep embodied listening, and by that I mean our ability to feel and allow our emotions and sensations. Change is crucial for clowns. We surf emotions, allowing ourselves to be visibly changed or affected by each encounter. It’s as if each person is a whole universe and as we enter their orbit we must adjust to their atmosphere, attune our breath, our sense of time, speed, rhythm, language, and our emotional landscape. If I expect anyone else’s universe to be the same as mine, I won’t be able to land. If I expect that it will be impossible, I won’t find a way. I have to arrive with no expectations, no judgments, about what is and isn’t possible.”

A sketch Suzie shared with us during her presentation of her sharing a love of fashion with a woman in a dementia care home.

The clowns must adjust to the new “atmosphere” of this shared world, and must recognise that this is a unique space which has never and will never be experienced in the same way by anyone else, nor by themselves and their interlocutors in a subsequent encounter. The consequences of this for rethinking normative academic understandings of what constitutes ‘evidence’ are, I think, clear, just as it reinforces the consensus reached in our first workshop about the need to adopt new and more flexible understandings of ethics.

This need for flexibility and attunement across all steps of the research process when working with people living with advanced dementia is perhaps the key emergent theme that I have taken from these first two workshops. Suzie summarised this sense perfectly when she said that we need to

“tune into the inner reality of the person, building trust and safety, and from this spacious place new possibilities open up, and new ways of connecting and experiencing are possible.”

This is what we are seeking to do in our work, and it is clear to me that we have much to learn from the artistic and performative approaches of therapeutic clowns such as Suzie.

The next blog will be by Dr Frankie Greenwood and will focus on Jane Bentley’s presentation at this workshop: “Meeting the Musical Moment”.