——Exploring the Process of Sound Restoration Through Field Recording, Sound Effects Editing, and Audio Synthesis

Dimple He & Jieqiong Zhang

1. Recording Blog

In our recording work, precision and efficiency are goals we constantly pursue. To ensure the perfect presentation of every scene and sonic detail, we adopted various professional recording devices combined with unique technical methods to establish a refined recording setup.

First, through a multi-point layout strategy, we planned each recording position in advance based on the spatial structure of the paper mill, ensuring comprehensive and multi-layered sound capture. This layout allowed us to create a wide-ranging and rich sound map, providing abundant material for later sound synthesis.

To adapt to changes in the on-site environment and real-time needs, we used dynamic on-site adjustments. During recording, we monitored and adjusted microphone positions and parameters in real time to respond to ambient noise and special sound effect requirements. This approach not only stabilized recording quality but also enhanced the expression of on-site sound effects.

In terms of equipment, we carefully selected high-performance devices to meet the demands of different scenarios. The Zoom H6 multi-track recorder, one of our go-to tools, is widely used for film sync sound and environmental sampling. Its multi-track recording capability allows simultaneous capture of multiple sound sources, ensuring clarity and detail, and played a major role in our recording work at paper mills and libraries.

To capture 360° ambient sounds at the paper mill, we used the F8 spatial recording device. This recorder captures the full panoramic soundscape, helping us reconstruct the overall atmosphere and providing valuable material for surround mixing in post-production. This gave our recordings stronger spatiality and immersion.

For specific detailed sounds, we relied on the Sennheiser MKH416. This highly directional and interference-resistant microphone is especially suited for capturing specific sounds in noisy environments, such as worker activity, machine startups, or chimes. It ensures these subtle sounds are recorded clearly and authentically.

Finally, we used the C-Ducer Contact Microphone to record sounds that are difficult to capture with conventional mics. For example, the alarm sound of fire detectors or the electrical noise of printers—vibrations caused by mechanical operation—can be picked up by this contact mic, offering richer sound information and ensuring no detail is overlooked.

Through these refined technical approaches and the integration of professional equipment, we were able to comprehensively and accurately capture and reconstruct various environmental sounds, laying a solid foundation for subsequent sound creation. Every step reflects our pursuit of technical excellence and extreme attention to sound effects, ensuring the final work delivers a realistic and vivid sonic experience.

1.1 Four Recording Devices

Key Recording Techniques:

Multi-point layout: Plan recording positions in advance based on the paper mill’s spatial structure to form a sound map with wide coverage and rich layers.

Dynamic on-site adjustment: Monitor recording in real-time, adjusting mic positions and parameters according to ambient noise and specific sound effect needs.

1.1.1 Zoom H6 Multi-Track Recorder

The Zoom H6 Multi-Track Recorder is used for multi-track synchronous recording, suitable for film sync sound, environmental sampling, and more. Nearly all the sounds we recorded at paper mills and libraries involved the H6.

1.1.2 F8 Spatial Recording Device

The F8 Spatial Recording Device was used to capture the 360° ambient sound of the paper mill, recording the full soundscape to support surround mixing in post-production.

1.1.3 Sennheiser MKH416

The 416 directional microphone was used to precisely capture detailed sound effects (worker voices, machine startups, chimes, etc.). Its high directivity and resistance to interference made it suitable for specific sound collection in noisy environments.

1.1.4 C-Ducer Contact Microphone

The contact mic was used to capture vibrations and mechanical movement sounds (e.g., fire alarms, printer electrical noise), which are difficult to record with conventional mics.

1.2 Three Recording Locations

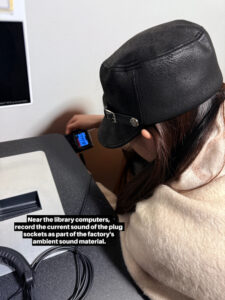

1.2.1 Library

In our library recordings, we focused on reconstructing the paper mill’s sonic landscape through systematic collection of multi-dimensional environmental and object sounds. By simulating the handling of paper, electrical sounds, water flow, and low-frequency mechanical noises, we aimed to not only recreate sonic textures but also explore how sound serves as a medium of memory and spatial representation. This process reflects creative strategies for sampling sound in constrained spaces and aligns with sound art aesthetics—”building scenes with sound” and “creating environments through objects”—offering expressive sound material for post-production.

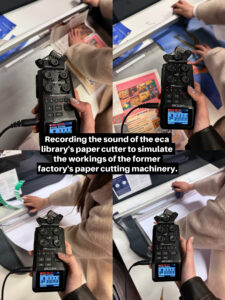

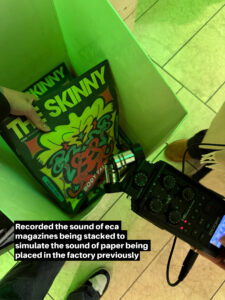

1.2.2 ECA

In the ECA campus recordings, we recontextualized everyday objects to simulate the sonic textures of paper processing and metallic machinery in old industrial environments. Metallic resonance from touching electric poles, the rhythmic sounds of paper cutters and staplers, the friction of wrapping paper and magazine stacks—these all evoke the tactile memory of past factory spaces. This method of “foley” in non-industrial settings demonstrates the mimetic strategies and symbolic coding in sound design. It also represents a kind of sound archaeology and artistic reconstruction of “lost industrial contexts,” transforming small contemporary sonic actions into reenactments of historical soundscapes.

1.2.3 Paper Mill

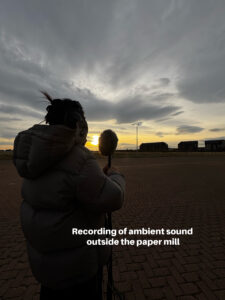

During on-site recording at the paper mill, we focused on the physical interactions between space and structure, reconstructing industrial memories through sound. By capturing natural ambient sounds outside the plant, we built an open, time-sensitive outer boundary for the overall soundscape. Inside the plant, the collisions and frictions—like sliding rails, iron gates, rolling shutters, carts, and aluminum strips—created a sense of mechanical texture and age. Footsteps echoing through factory corridors offered auditory cues for simulating the rhythm of daily worker activity. These sounds go beyond physical documentation to form an auditory archive, allowing present-day listeners to “hear” a vanishing industrial memory field through spatial acoustic detail.

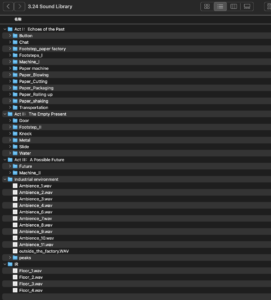

2. Sound Library

2.1 Audio Editing

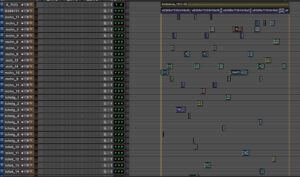

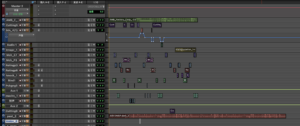

To prepare for randomized audio processing in Max/MSP and Logic Pro, and to provide trigger signals for random visual generation in TouchDesigner, we initially selected and trimmed the recorded audio. Based on the three main scenes and their respective environments and impulse responses (IR) defined in the project script, we categorized the organized audio as foundational resources for further creation.

2.2 Sound Effects Design

Our goal in sound design was to present each detail flawlessly using precise techniques and creative design, creating atmospheres tailored to specific environments. By artistically processing the recorded audio, we produced various sound effect fragments across categories, scenes, and objects. This process involved not only precise editing but also layering creativity and emotion, ensuring each effect possessed expressive power in its intended context.

We performed full audio processing on the recordings. EQ adjustments allowed us to selectively boost or reduce frequency components, ensuring each sound remained clear and balanced in the mix. Low frequencies emphasized machine operations or factory rumble, while high frequencies highlighted mechanical details. Compression controlled dynamic range, avoiding distortion and ensuring every detail was clear. Reverb and delay enhanced spatial and temporal depth, enriching the interplay between ambient and detail sounds.

To further enrich sound effects creatively, we used acceleration and pitch-shifting techniques. These added rhythm and emotional tone—e.g., acceleration simulating rapid machinery, pitch-shifting conveying deformation or emotion.

We also used tools like the Serum wavetable synthesizer to generate some sound elements. With its advanced synthesis capabilities, Serum enabled precise creation of scene-specific sounds. We used it to simulate machine startups, metallic friction, and air vibration—particularly effective for large industrial environments like paper mills.

By adjusting Serum’s details, we generated time-specific industrial sounds. For example, modern equipment sounds were high-pitched and metallic, while older equipment produced deep, booming rumbles—adding a temporal dimension that linked sound evolution with historical changes in the factory.

Serum’s multidimensional modulation offered extensive sound transformation options. By tweaking oscillators, we simulated various paper mill sections: the pulper’s low hum, the high-frequency friction of the paper line, even steam and compressed air hiss—each presented through Serum’s modulation tools and merged with original audio for richer texture.

For background ambiance, we used Serum to synthesize low and mid-frequency environmental noise, simulating factory operational background. This avoided awkward silences and added fullness, enriching the overall soundscape without relying solely on field recordings.

This creative combination of synthesizers and field recordings broke through traditional design limitations, expanding possibilities in complex industrial sound design. The flexible, artistic approach captured unique and intricate sound elements, maintaining both technical accuracy and artistic freedom.

As our sound material grew, we began creative layering, the core step in our process. We organically merged ambient and detailed sounds, enhancing expression. Through multi-track mixing and layering, each segment retained presence and responded dynamically to scene needs. This process made our sound design more refined and compelling.

Finally, we integrated the sound effects with visual tools like TouchDesigner, ensuring smooth, natural interaction between sound and visuals. Sound wasn’t merely atmospheric—it functioned as a core element complementing the visuals. We fine-tuned every scene’s soundscape for emotional and expressive unity.

Conclusion

This series of sound design and processing efforts helped us construct a multi-dimensional sound world, giving each scene depth and dynamism. Through careful creativity and technical methods, we not only recreated the reality of paper mills but also delivered a deeply immersive audiovisual experience for the audience.

Attached is our produced sound library: