When Helen Lowe conducted her campaign in favour of the preservation of the special status afforded to the Bruntsfield Hospital for Women and Children and the Elsie Inglis Maternity Memorial Hospital as hospitals staffed exclusively by female medical professionals, her experience taught her a great many lessons on the running of an effective campaign. Luckily for us, we can access these lesson and learn from Helen’s success. Here are some of the tips and tricks that Helen’s papers –hosted by the Lothian Health Services Archive—seem to recommend:

1. Have a clear objective

Sometimes, issues surrounding certain specific campaigns can be complex and multi-faceted. It is important, however, to keep actions focussed on specific aims and to be able to explain those aims concisely and clearly.

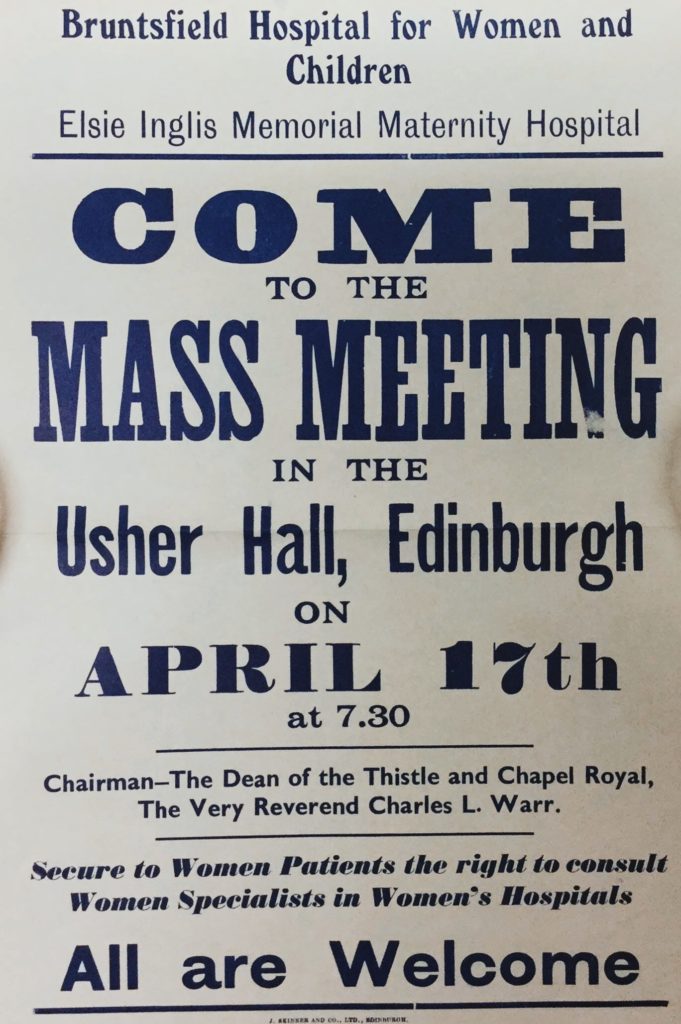

‘A mass meeting is to be held in the Usher Hall on Wednesday, April 17th at 7.30 p.m. with the object of passing a resolution to initiate action to safeguard the maintenance of the status quo of the […] hospitals as hospitals for women patients, staffed by women.’

Despite not being unaware of the larger issues facing female medical staff and patients throughout Scotland and the UK, Helen knew that in order for her campaign to gain momentum, it needed to maintain a solid, central statement of intent. This ensured all efforts would be geared toward achieving the most important or most pressing goals.

2. Find allies

As Helen’s correspondence demonstrates, building a strong network of interested participants in relevant organisations and institutions is fundamental to a fruitful campaign. And it’s important to remember that allies can be found where one least expects them:

‘Several of the most distinguished medical men in Edinburgh are on the side of the women.’

Despite the staffing of the hospital being primarily a female concern, gaining the trust and support of ‘the most distinguished medical men in Edinburgh’ proved an essential boost for Helen’s campaign, for it served to fight the gender stereotyping attached to the issue, and thus leave space for more administrative, medical and legal discussions.

3. Raise public interest

Support from appropriate political, professional or cultural groups can certainly do much to improve the chances of a campaign, but nothing is more powerful than public opinion. As Helen puts it in one of her letters:

‘The wider the support, the more likely we are to succeed.’

Once the aims and methods of the campaign have been established, it is time to shout about it and make sure more and more people take the cause to heart.

4. Create easily actionable tasks

Getting people to listen to your concerns is certainly an essential part of the success of a campaign. Taking action, however, is what makes the difference. So as to encourage a larger number of supporters to transform that support into action, it’s important to come up with simple and effective steps that everyone can take with relative ease:

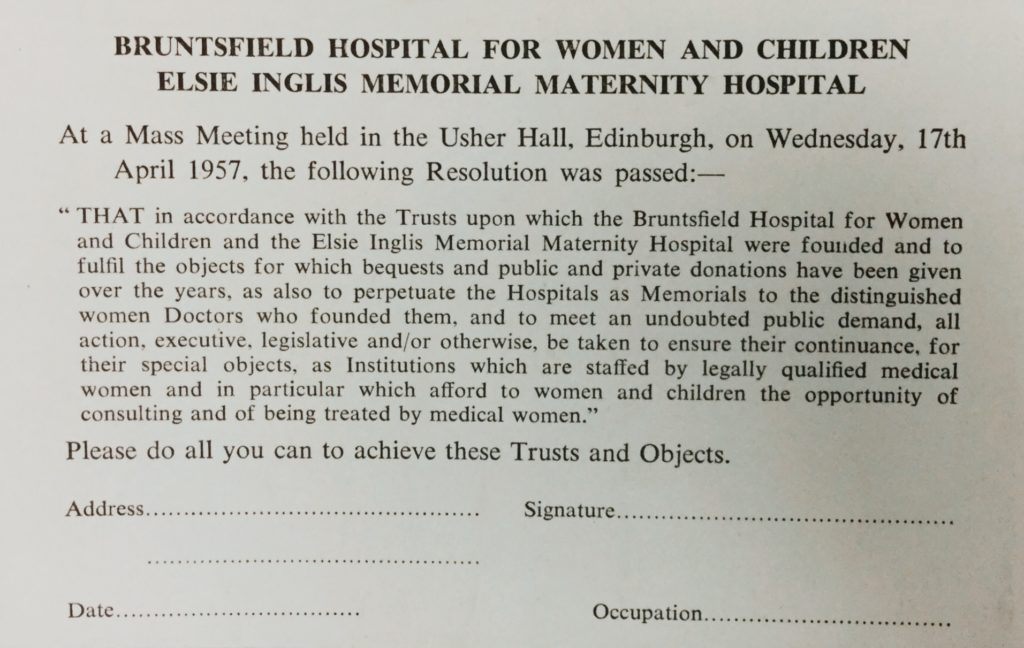

‘At the meeting each member of the audience took away a card […] in order that they might send it to their Member of Parliament. […] We wish to impress our Members of Parliament with the sincere demand there is for the retention of the women’s hospitals.’

By providing all supporters with a pre-written postcard, Helen ensured that everyone who wished to take part in the action to save the hospitals would be able to do so without requiring too much effort or commitment.

5. Avoid misconceptions

Sometimes, information doesn’t seem to come across the way it is supposed to. Be it the consequence of an honest mistake or an attempt on the part of the opposition to sabotage the action, this can result in losing supporters and, in the long run, will damage the campaign. In order to avoid misunderstandings, give supporters, allies, and collaborators a chance to ask questions and clarify issues. As a letter to Helen states:

‘Another lady, who has now sent a card to her MP, said that she had refused to sign before because she was under the impression that this was an anti-male doctor campaign. She now fully understands the situation. ‘

The mass meeting in Usher Hall offered Helen and the other campaigners an opportunity to set the record straight as to the aims of their campaign, so that supporters could be reassured in their loyalty to the cause.

6. Oppose misrepresentation

Media coverage can be a significant ally for a campaign, yet not all press is indeed good press. When issues at the core of the campaign get repeatedly misrepresented, the campaign’s aims run the risk of becoming overshadowed. As Helen’s letters to newspaper show us, accurately and systematically opposing misrepresentation allows for the running of a fairer and more open campaign:

‘Mr. Nixon Browne, however, in his reply as reported made statements which could lead to serious misconceptions.’

With politeness and decision, Helen called out Mr. Nixon Browne’s ‘misconception’ as to the campaign and the way the press had reported on these, so as to project a more accurate image of the struggles to maintain the status of the hospitals.

7. Do not give up

Setbacks are a natural part of every campaign. Thinks don’t always run smoothly, and, sometimes, carefully planned action doesn’t lead to the expected results. Don’t lose heart, though.

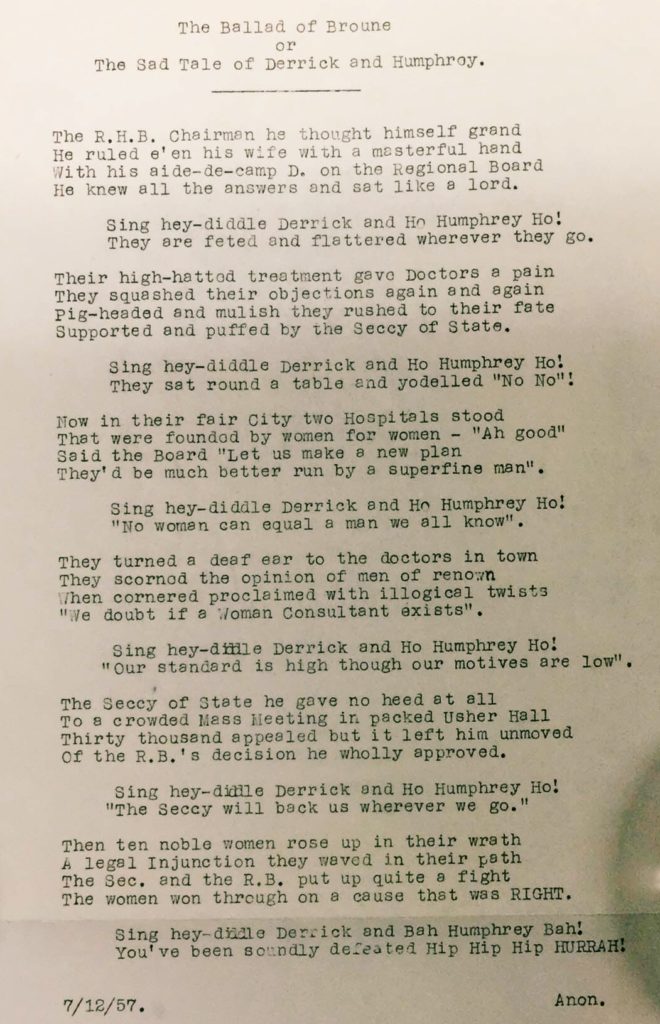

‘It was decided at the meeting to pursue our cause until Justice is done. ‘

In the face of failure, it’s crucial to remember the reasons behind a campaign, and to know that, with the support of allies and a little extra time and effort, anything can be achieved.