Born in Inverness on 4th March 1941, Dr Margaret Melville Rae Martin, known to friends and family as simply Rae, was a member of a distinguished medical family. Her mother, Margaret Wylie Martin, and her father, Russell Dickson Martin, met while working as doctors in the Inverness area, with Dr Russell Martin serving as Medical Officer of Health for Clydebank at the time of her birth. Her paternal grandmother, Dr Emily Winifred Dickson, was also a medical practitioner and the first woman to be appointed Fellow of the Royal Academy of Surgeons in Ireland.

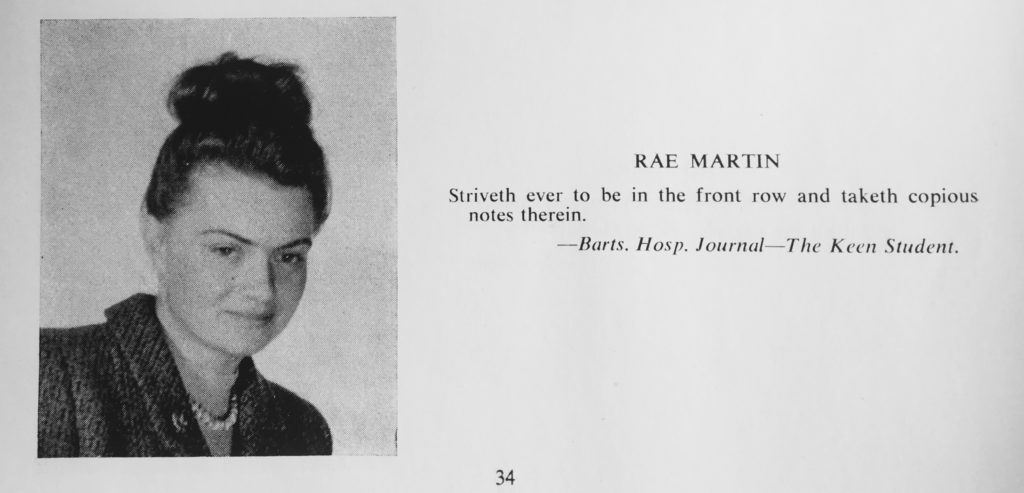

After gaining recognition from the Scottish University Entrance Board, who, in 1958, certified to her ‘fitness to enter upon a course qualifying for graduation in any faculty in a Scottish University’, Rae decided to follow in the footsteps of her family, and, in 1959, began classes at the Medical School of the University of Edinburgh. Soon after her enrolment, Rae was granted the Whiteside Bruce Bursary, ‘awarded [to her] as the student who, having attended the Chemistry, Physics and Biology classes during the past winter and summer sessions, had obtained the highest number of marks in the class exams in these subjects.’ A diligent and brilliant student, Rae graduated with Honours in 1965, winning, in the same year, the Buchanan Scholarship in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and being appointed part-volunteer doctor in Labrador (Canada) under the International Grenfell Association.

Upon her return from Canada in 1966, Rae took up a series of posts throughout Scotland, first as House Surgeon in the General Surgical Unit of Bangour General Hospital in West Lothian, then as House Officer in the Simpson Memorial Maternity Pavilion and Gynaecological Wards of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh – where she was promoted to Senior House Officer—and Senior House Officer in the surgical department at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh, and, finally, as Resident Registrar at the Royal Samaritan Hospital for Women in Glasgow. In October 1972, she admitted to the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

Her interest in travelling, sparked by a medical volunteering trip to Poland in the early days of her career, led Rae to move, in 1973, to Ethiopia, where she worked at consultant in charge at St. Pauls Hospital in Addis Ababa. While in Ethiopia, Rae also held the post of honorary assistant professor at the university in Addis Ababa, as well as taking part in the training of nurses and family planning workers. From 1974 onwards, Rae also covered a part-time position as gynaecologist at the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia, and was appointed official lecturer to the Ethiopian Family Planning Association.

In 1976, after almost four years abroad, Rae decided to permanently return to the UK, taking up a job as consultant at Newmarket General Hospital in 1977, where she remained until her retirement in 2001. In 1985, Rae was awarded a Fellowship to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and in 2005 she became a Fellow of the British Medical Association, an organisation she had partnered with for over 25 years.

Always keen to share her medical expertise and to visit new places, during her time in Ethiopia Rae attended numerous conferences in Northern Africa, forging connections with local medical practitioners and fostering her passion for travel and photography. Her travel accounts, held with her professional and personal papers in the University’s Special Collections, are rich of vivid descriptions of the places she visited and her encounters with local culture and fellow travellers. Often irreverent and ironic, Rae demonstrates in her writing a vivacious character and a witty mind:

The club is near the fort of Quait Bay –15th C. now a museum and officially a military object – and not photographable! I did! –the guardian agreed it was a stupid rule.

Ever self-aware and keenly independent, Rae was capable of appreciating the liminality of her position as a female doctor and surgeon, jokingly remarking on the perceived paradox of it in one of her journals:

The men went sightseeing in old Cairo after lunch, but the ladies –and I was temporarily a lady, not a surgeon – were invited to the presidential house.

Rae’s witty explanation that she could either be a ‘lady’ or a ‘surgeon’, but never both at the same time, speaks of her understanding of the social constraints to which female doctors of her time seemed to be subjected, but her willingness to slip ‘temporarily’ from one role into the other at her will highlights her desire to live freely, and makes us agree that the depiction of ladies and surgeons as opposite too was, indeed, ‘a stupid rule.’