Opening Worlds

Arkotong Longkumer

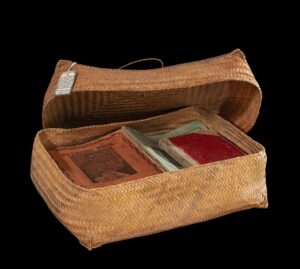

A basket opens worlds. It is a receptacle that carries and holds many things. When you open the lid of a basket and peer inside, it can reveal heirloom materials, personal items, agricultural tools, food wrapped in plantain leaf, or even seeds to plant during the sowing season. The basket in this collection is a pliable weave that is soft, like a textile, on the body. It is used for carrying. The colour has darkened through use, but it also gains that colour by keeping it near the fire – the smoke seasons the texture.

This basket is one of the 27 personal items belonging to Rani Gaidinliu (1915-93), now known as the Gaidinliu Collection. Rani Gaidinliu was a Naga leader, prophetess, and a woman of storied courage. She was only 16 in 1932 when the British captured and imprisoned her. She was accused of organising a revolt against the British administration and released from Tura prison (in the Indian state of Meghalaya) only after Indian independence in 1947. Even after her release, she was restricted by the government and made to stay for 10 years of her life in Yimrup, a Chang Naga village in eastern Nagaland, although she was eventually allowed to return to her native village of Lungkao in Tamenglong district of Manipur. Placemaking is a marked presence in her life, moving across the Naga homelands from Lungkao (Manipur), her birthplace, to Hangrum (Assam), Poilwa, Yimrup, Mokokchung and Kohima (Nagaland), traversing the natural paths across these interconnected geographies, now bounded and marked by the states of Assam, Nagaland, and Manipur.

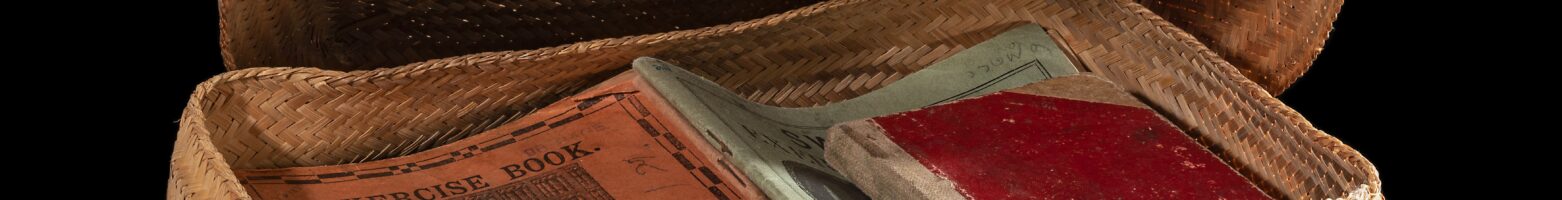

In the catalogue description above, the basket is used as container to store 12 notebooks belonging to Rani Gaidinliu. What are these notebooks and why are they vital in understanding the lifeworld that Gaidinliu inhabited and created? The notebooks are written in a language that is largely untranslatable in the conventional sense of stringing a sequence of words and letters together. Yet, it contains myriad possibilities and a language rich in symbology, textured in the world that she inhabited. The notebooks inscribe stories, patterns and designs that tell us about Gaidinliu’s own weaves – comingling with the knotted plant fibre of the basket, the hands that shaped its twills, and the knowledge infused in its making. As Tim Ingold eloquently puts it, ‘Only if we are capable of weaving, only then can we make’. The woven basket, and the notebooks, are about a continuous process of becoming, where objects continue to interact with the work of the hand, and in a broader sense are uncontainable in the confines of the museum. Things are constantly made and remade.

Attached to the basket is a label with this description: ‘Basket of note-books belonging to the sorceress Gaidiliu [sic] containing scribbl’d characters purporting to be writing. Her supposed literary powers gave her great prestige. Hangrum village, N. Cachar Hills, J.P. Mills 1932’. Here the language of colonial power enters the world of Gaidinliu with its vocabulary of conquest, power and denigration. She is vilified as a ‘sorceress’ and her writings dismissed as ‘scribbles’. Amidst these accusatory judgements, she is viewed as a threat and her personal items abducted to the Pitt Rivers Museum to be kept under lock and key, in a different temporal and cultural space altogether. The basket becomes a preserved object, with its own accession number, a museum piece.

In 2024, when we conducted a community-curated workshop in Tening, Nagaland, a Liangmai basket weaver, Huluakbo, from Nzau village, came to the event, intrigued to see the Gaidinliu collection. He immediately recognized the large print of the basket on photo sheets we had installed for the workshop. He then demonstrated on the spot the interlacing of the warp and weft of the bamboo splints plaiting a crisscross pattern. It was difficult to know if he was copying the basket from the picture, or it was bodily memory. We later interviewed him, and he remarked how Gaidinliu’s basket is unique in style and geometry, how it was a receptacle to keep her precious things, so that they can be protected from theft or natural calamities like fire. To evade capture and confiscation, he noted, she also kept the basket inside the cave when she was hiding from the British. Perhaps the rocks, earth and the damp and humid atmosphere of the cave also contributed to the texture and colour of the basket.

We asked him to make a replica. We enquired about his method of making and he replied that all he needs is a sharp dao (hacking knife); the experience of the weaver means that the shape and size of the basket depend on an attention to detail and patience that has been cultivated through the years. We were unsure if the 3D modelling of the basket that we shared on a tablet and print image of the basket would enable him to replicate the basket. Huluakbo told us that once he sees the pattern and the design, the body takes over. We asked him to interpret the image of the basket, and not simply to create an exact replica of it. We wanted to see how contemporary and traditional methods combined to produce new designs. He made a twill woven basket, a contemporary interpretation of basket, now gifted to the Pitt Rivers Museum with its own accession number.

We asked another Rongmei basket weaver in Churachandpur district of Manipur, P.G. Meijendai, to create an exact replica of the Gaidinliu basket. Upon seeing the image of the basket, he vaguely recognized the design but wasn’t sure of the material. Initially he thought it was a common type of cane or bamboo, but when he shared the image with his friends and family they said it was a particular kind of bamboo fibre that is only available in the forest of the hills of Manipur. He found some in Lungkao, Tamenglong district of Manipur, the place of Gaidinliu’s birth. He identified the bamboo fibre as nik (in Rongmei) which is a bamboo species called Bambusa multiplex. This is what he told us:

Nik is a particular type of bamboo that is smaller in size. It is smooth and cylindrical, primarily greenish in colour with some brownish parts. The sticks vary in length but generally maintain uniform thickness. Some are slightly curved, and they are flexible, making them ideal for weaving baskets.

Since the sticks were freshly cut from the jungle, they were still raw and not dried. A basket can be made using either raw or dried nik, but not at the same time. If the sticks were dry, I would have had to soak them in water before use. However, since mine were raw, I could start immediately.

Before cutting the sticks, I first scraped off the rough parts to smooth them. Then, I cut each stick in half and carefully sliced them evenly. Only the outer layer of the bamboo is used, while the solid inner part of the stick is discarded. The outer layer is sliced with extreme care to ensure precision. If the sticks are not sliced uniformly, the basket will not achieve the desired look from the reference picture and will also be difficult to weave.

Meijindai preparing the nik stems for basket weaving.

Meijendai pointed out that hands are vital to the process as they are the only natural tools used to weave different styles and shapes. In the hands, the sharp knife needs to be handled with care to prevent injuries, slowing down the process of weaving. While nik is the main fibre in the basket, providing flexibility and strength, two crossed strips of bamboo sticks form the base and the lid of the basket, these are used to make the basket uniform in its dimensions.

Meijendai reflected on the importance of the basket in traditional life as it was widely used to store things as people had no wardrobes or cupboards. Baskets were used to store clothes, to carry water or firewood, or to keep jewelry and personal items. Baskets made from nik were given to special individuals. This basket, he notes, is unique because it is rectangular and not the commonly used square shape. Moreover, a basket made from nik symbolized love and lasting bonds. ‘There are different names for different types of baskets used for various purposes. I will refer to this particular basket as Haipei [everyone’s grandmother] Rani’s Basket’. For Meijendai, the hands that made the basket reveal the kinship bonds with Haipei Rani, an honorific term that is reserved only for Gaidinliu.

Like the Liangmai basket, this basket stands on its own, a separate piece, with its own name, presented to the museum to demonstrate a gift of love and respect for a woman who is Haipei. It is uniquely hers. Although it is now in the museum with its own accession number, it is more than an object. It is a living embodiment of a people and culture that has withstood time’s relentless melt. It is now for the world to see, side by side with the other baskets.

The basket in Gaidinliu’s collection has taken on a life of its own. From the tumultuous period of her life in the 1930s when her belongings were taken and her imprisonment in India began, her basket remains a testament to the stories it continues to narrate and the inspiration and creative imagination that it cultivates. Now digitised, it circulates in social media, perhaps viewed as photographs of cherished objects, but also now in its material form of replicas through the Liangmai and Rongmei baskets. It is not simply an object, absent in content or form, but it builds worlds – worlds that have travelled from the Naga homeland to the confines of the Pitt Rivers Museum, back to the community of origin, and then returned to the museum as a gift. The circle continues and asks pressing questions around agency, and the ability for the basket to reveals secrets and knowledge of a world that is alive. The baskets inhabit bodily memory, as receptacles to store things and weaves that continue to hold knowledge of tradition and the world around us. The Naga historian, Alemchiba Ao, writes how a Naga starts their life in a ‘cradle of bamboo and end in a coffin of bamboo’ (1968; cited in Odyuo 2008, 161). And a basket, Iris Odyuo notes, always accompanied them to the land of the dead. Dwelling is a form of belonging where the bamboo continues to extend its fibres to the very being of existence. Weaving then is the experiential ground upon which we continue to make and to live.

My thanks to the research assistants, Lanchamei Golmei in Manipur and Thoizai Newmai in Nagaland, and to Gaurav Rajkhowa for assisting with the interviews. And to Iris Odyuo for her advice on basket weaving in general.