By Rebecca Keegan

“...[T]here is no such thing as "keeping out of politics." All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia.’

- George Orwell, 1946

The Indian Papers Collection can provide us with important information, but we must recognise the lens in which it is filtered through; the British imperialist one. Whilst the papers are Indian, the ink is British. By using AntConc it enables patterns to be identified which demonstrate how, and to what extent, medical decisions depended on political motives.

Imperial interest in British India

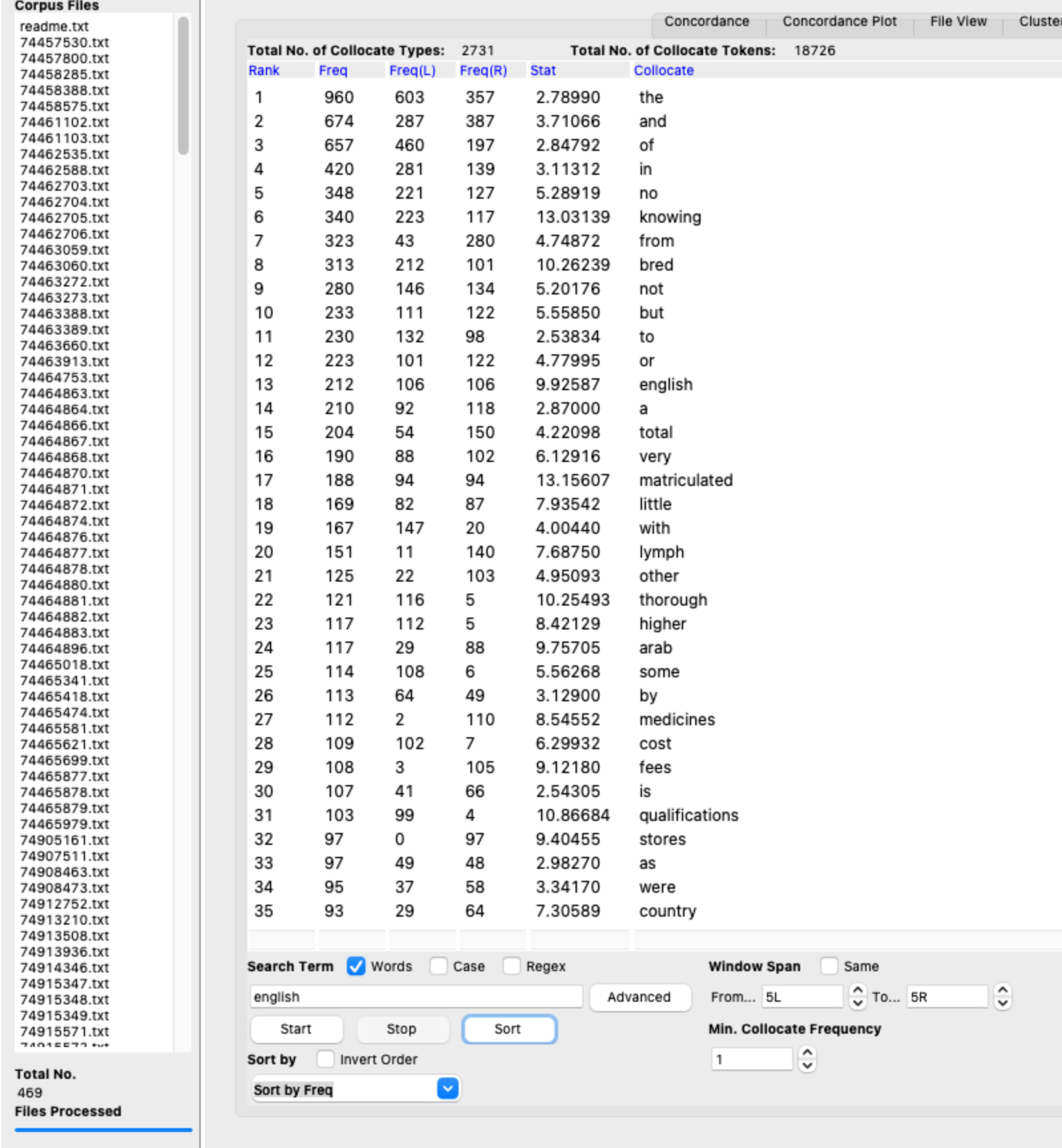

What was the British Empire’s interest in these medical records? They had to be able to justify their place in India, to be seen as bettering the nation. A search on AntConc for ‘English’ shows the most common words appearing alongside it.

Figure 1: AntConc search for 'English' showing the most frequent words appearing alongside it.

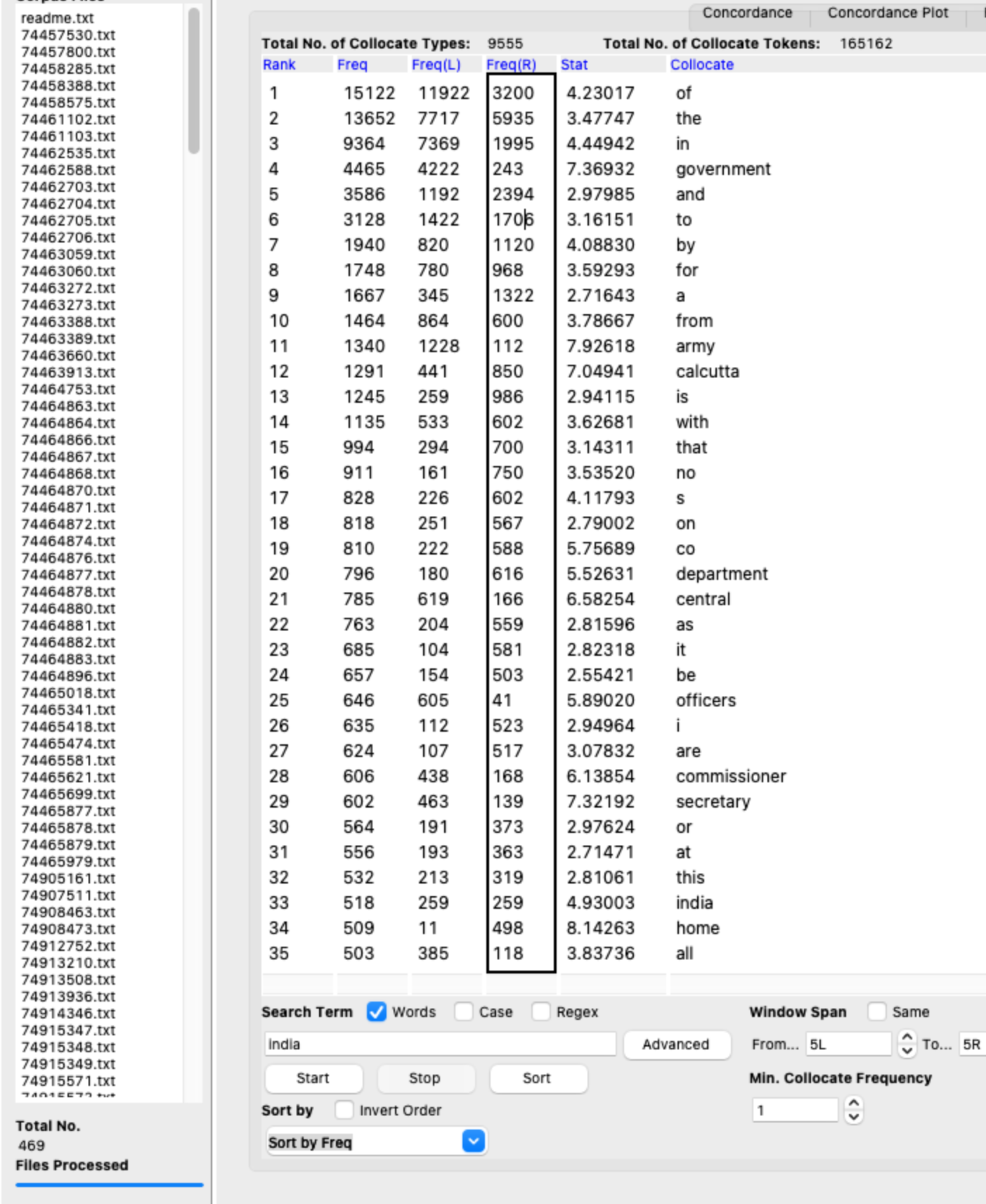

High up on the list are words such as ‘knowing’, ‘from’ and ‘bred’, these suggest that when discussing England, it is being framed within the context of knowledge, receiving and breeding. When compared to the same search but for ‘India’ the results show the difference in how the two nations are presented within the texts. Some of the most common words are ‘to’, ‘for’ and ‘government’, advocating ideas of receiving and benefiting as well as overt political ties with the mentioning of ‘government’.

Figure 2: AntConc search for ‘India’ showing the most frequent words appearing alongside it.

It is clear that there is a difference in the representation of the two nations by the way they are discussed in the texts, with England portrayed as the benefactor to India. By depicting India as a subordinate to England, it is evident how the discourse enables colonial ideologies to be propelled. Throughout the texts as whole, there is clearly a pattern of politically implicated language.

Even more crucially, the practice of archiving is traditionally conflated with colonialism. Smith argues how the archives themselves assist the colonial cause, ‘‘The scholarly construction…makes statements about it [the Orient], authorising views of it, describing it, by teaching about it, settling it, ruling over it.” (31) The political implications are therefore two fold; both within the texts and in the gathering of the texts themselves.

Political Danger

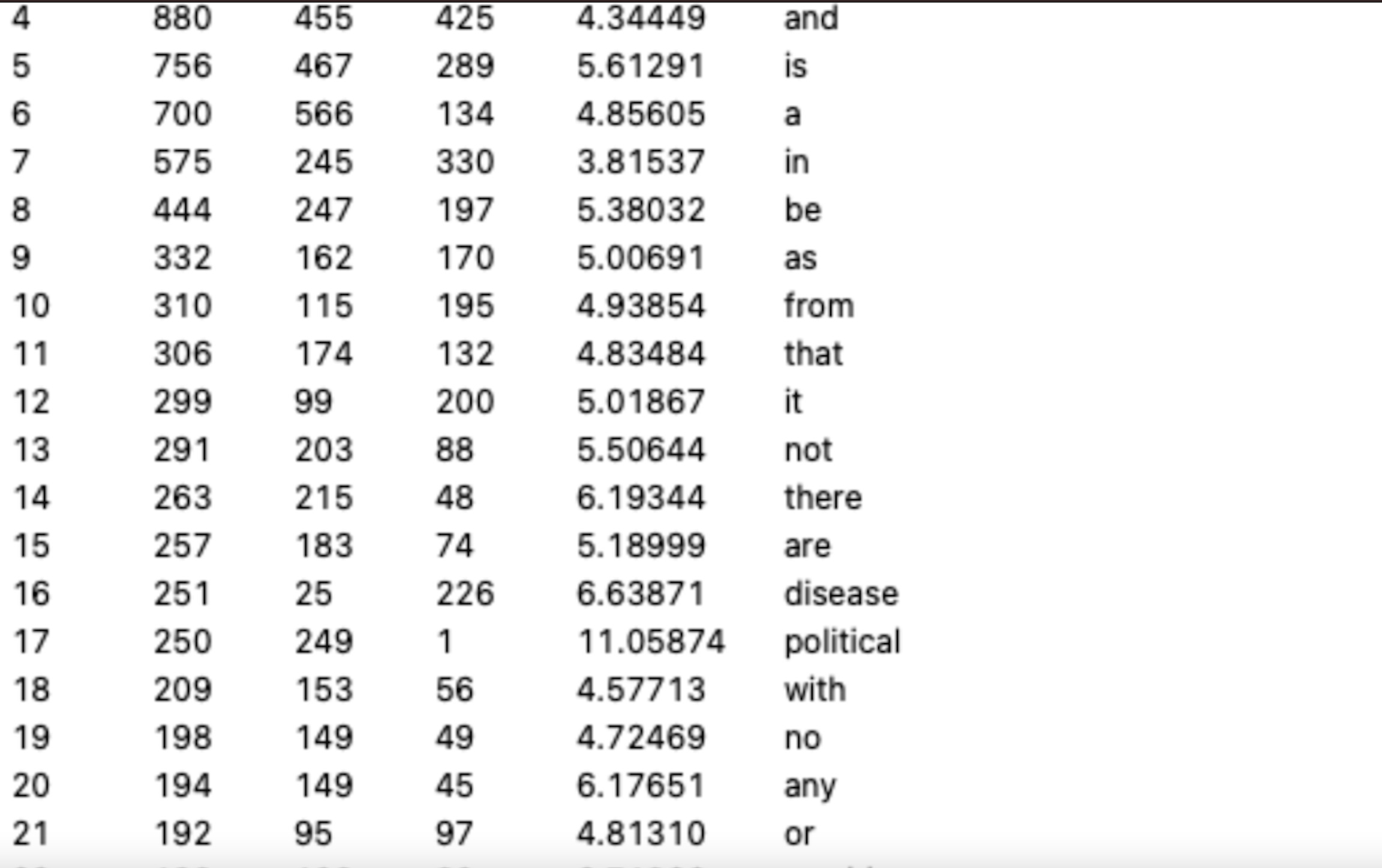

There are explicit mentions of political concerns within the collection which serve to highlight the connectivity between politics and medicine. When ‘danger’ is being discussed there are two adjectives that commonly appear alongside it; ‘disease’ and ‘political’ (see figure 3.)

Figure 3: AntConc search for ‘danger*’

Considering the papers are about the medical history of India, it is not a surprise that diseases are being discussed, however political danger is being discussed almost as often. This begs the question, or questions, what is the political danger and why is it so important?

There are 248 instances of the term ‘political danger’ within the papers. The context of these mentions surrounds the question of whether or not medical decisions (for example, a ban on certain drugs) would cause any political unrest.

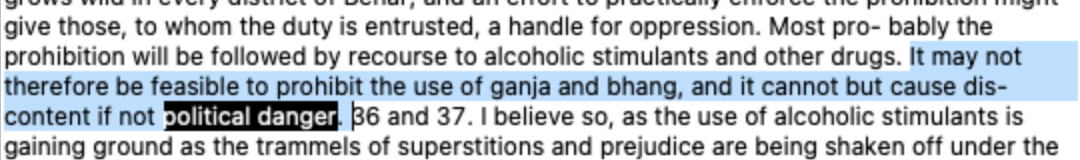

Figure 4: Text file 74462706 as an example of political danger, ‘yes, there would be serious discontent, though no political danger.’

Figure 4 shows that medical decisions are being discussed according to its social effect. The division between ‘serious discontent’ and ‘political danger’ demonstrates a willingness to risk creating grievances but not anything that could threaten the political power of the British Empire.

Figure 5: AntConc search for ‘Political Danger*’ sorted with words on the left.

Furthermore, the majority of these instances are stating that certain decisions would ‘not amount to political danger’ demonstrating that political stability was clearly valued. Politics markedly plays an intrinsic part to these records, as when discussing medical decisions they are framed within a political outcome. Was politics given precedence over health?

‘Native doctors’

The political implications do not just concern policy making, but also the physical practice of medicine itself. The notion of a ‘native doctor’ appears 556 times within the collection. The term is used to describe indigenous doctors who were trained in Western medical practices (Saini 2016). The decision to label these doctors as ‘natives’ serves to further the political colonial agenda, as conflating ideas of local and home with medicine, hides the reality of the Westernised doctors, perhaps enabling the practices to be more accepted within India.

Figure 6: AntConc search for ‘native doctor*’

Saini further notes the importance for this medical teaching as ‘The British tried to prove their supremacy in every field including medicine to justify their rule in India’ (531). The subterfuge of the term ‘native doctor’ was to gain the trust of the Indian people, whilst also being able to prove the superiority of western medical practices to the world.

A close reading of ‘native doctor’ mentions uncovers tensions between these doctors and other medical professionals. Mushtag writes ‘The people of India resisted the British colonialism, and they were reluctant to support any services by the foreign government.’ (2009) The resistance can be demonstrated by Figures 7 and 8, showing the supposed inadequacy of the ‘native doctors’.

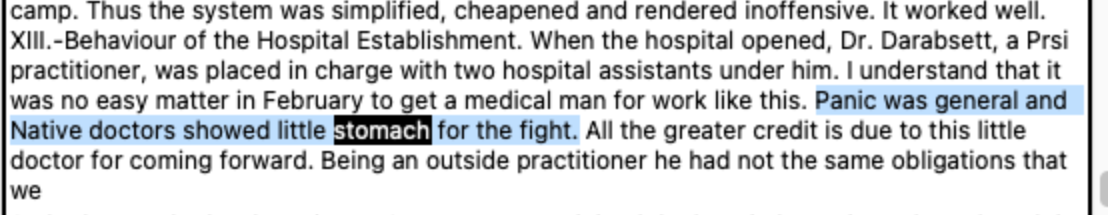

Figure 7: Text file 74465474 as an example of frustrations with a native doctor, ‘Panic was general and Native Doctors showed little stomach for the fight.’

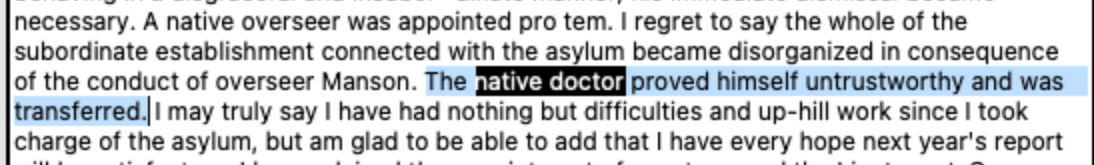

Figure 8: Text file 83377957 as another example of frustrations with a native doctor, ‘The native doctor proved himself untrustworthy and was transferred.’

However, these examples bear little impact upon the vast majority of the other instances of ‘Native doctors’ within the collection, in which they are regarded within positive terms.

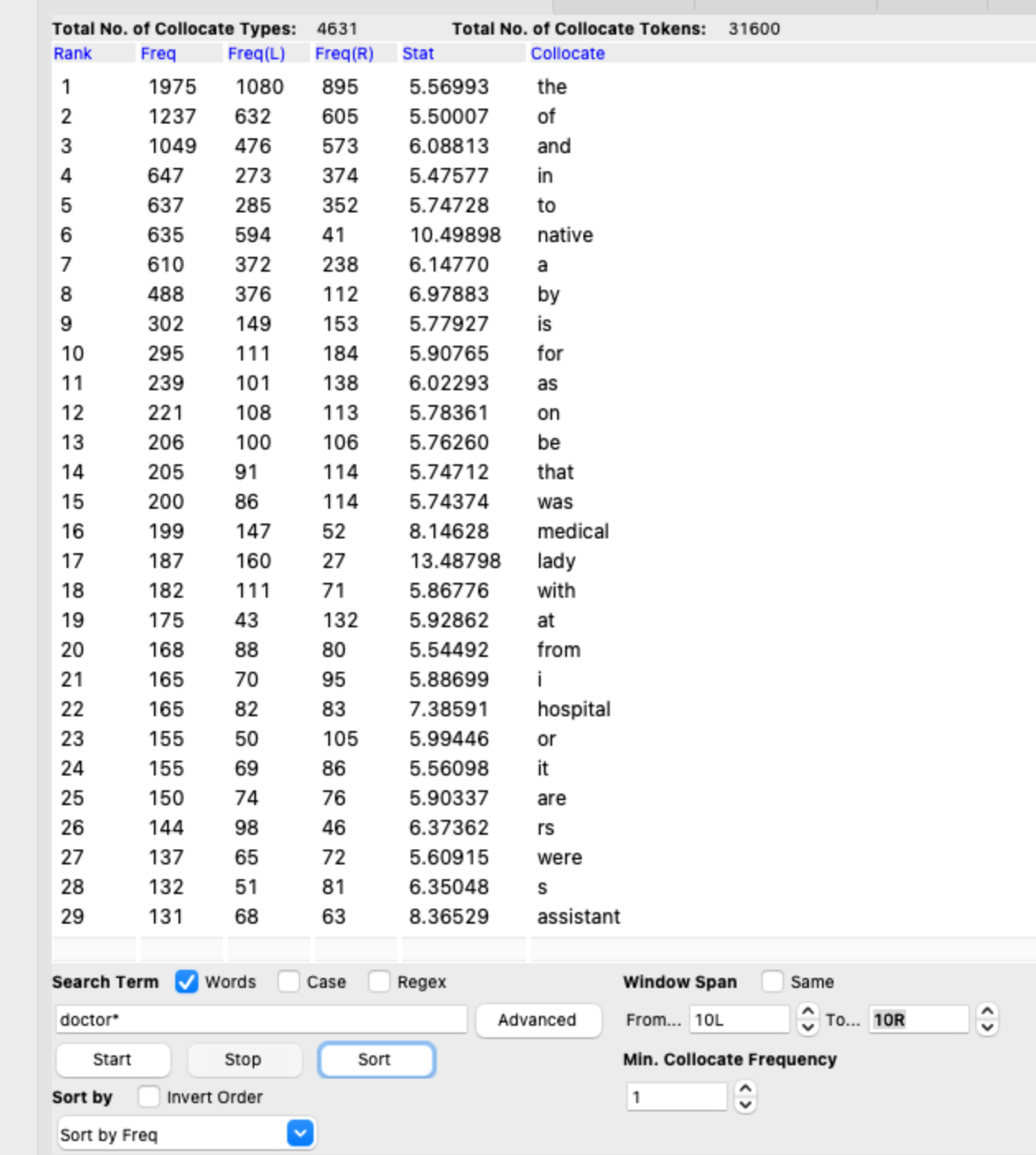

Furthermore, the influence of these native doctors has been shown to be extensive (see figure 9) as a large percentage of mentions regarding doctors, is referring to the ‘native doctors’ specifically; ‘native doctors’ seen as a colonial tool for Western enterprise, the collection is evidently furnished with politically motivated content.

Figure 9: AntConc search for ‘Doctor’ collocates, organised by frequency.

Conclusion

As Orwell famously stated, we cannot escape politics. The India Papers Collection is no exception as it exhibits a multitude of examples demonstrating how politics is inextricably tied to medicine and health. These medical records are not apolitical and we must be careful not to present a medical finding without first acknowledging and understanding the politics dominating it.

Works Cited

Mushtaq, Muhammad Umair. “Public health in british India: a brief account of the history of medical services and disease prevention in colonial India.” Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine vol. 34,1, 2009, pp. 6-14.

Orwell, George. Politics and the English Language. 1946, https://www.orwell.ru/library/essays/politics/english/e_polit/ [Accessed 05/12/2020]

Saini, Anu. “Physicians of Colonial India (1757-1900).” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, vol. 5, no. 3, 2016, pp. 528–532.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books, 2012, pp. 30-32