By Natalia Covarrubias

“The most noticeable fact concerning the housing of the inmates is the very excellent ward under construction for the accommodation of the non-criminal lunatics; but arrangements should be made, if possible, for subdivision of the criminals into classes, viz., those who are filthy in their habits and those who are not. It is almost enough to make a sane man mad to lock him up all night with such filthy brutes as many of these unfortunates have become” (A Medical History of British India)

When it comes to working with archives from colonial lunatic asylums a temptation for the humanist scholar might be to try to reconstruct the lives of the people who were there, to find their voices and experiences. However, the reality is that the records available to us were not meant for that purpose. For the Colonial Office, as Sally Swartz argues in ‘Asylum Case Records: Fact and Fiction’, the archives were a statistical tool to supervise the asylums from afar: ‘counting and comparing, ordering and budgeting, measuring room size and numbers of bathrooms and pieces of bread’. At first glance, it might seem that the insight we were hoping to find is not there, but precisely, under that layer of classification lays the meaning. As Swarts describes it, this quantification was also 'a performance of something, a rhetorical device, language, a metaphor, bearing a relationship to that which it described. Standing in place of it. Not the thing in itself'. What it is practiced here is the colonial discourse around the ‘insane’.

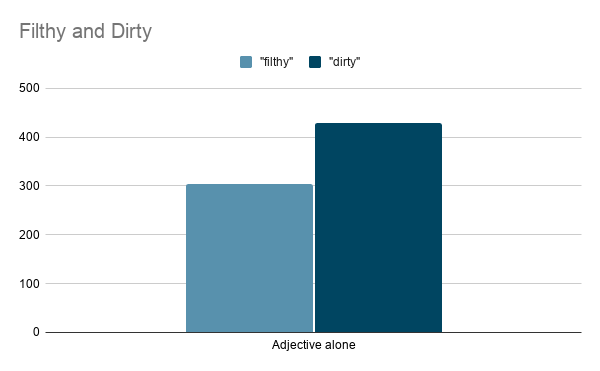

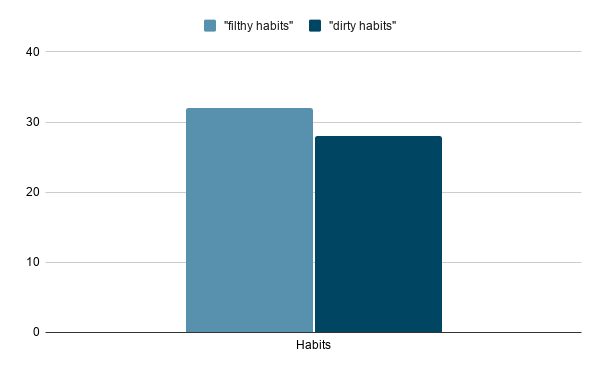

Following this approach, we start to pay attention to the data. James Mills, working with the case notes from the Lucknow Asylum, notices not a reference to the actual mental state of patients, but rather a recollection of data on their physical condition and behaviours. Prompted by this, I decided to search for the words employed to describe the habits of patients. Looking at medical reports, it is common to encounter descriptions of unhygienic circumstances to explain how sickness can be physically caused and/or aggravated by infections. However, the word ‘filthy’, a more extreme version of dirty, is often used instead (see fig. 1 and 2). How is filthy being understood that it was chosen to describe let alone objects and places in a strictly medical setting, but also habits, conditions, and human beings?

Fig. 1. 'Dirty' vs ‘filthy’ appearances.

Fig. 2. ‘Dirty habits’ vs. ‘filthy habits’ appearances.

In 2020, more than a century after these reports were written, the terminology around health has definitely changed. What is remarkable is the underlying attitude certain choices of words reveal. The peculiarity of the use of ‘filthy’ in these texts is that it most frequently alters the subjects which are already in a position of being imposed, of being vulnerable. To this matter Coleborne has noted: ‘The insane as subjects, always already “subaltern” by virtue of their perceived “madness”, are highly mediated by virtue of their status as patients in a clinical setting’ (129). As follows, our knowledge of the mental state of patients in the Asylums of British India is obscured by alterations of different kinds. Not only are patients segregated by their race, but they are also being seen as not mentally able, and in addition to that, they are judged based on their habits.

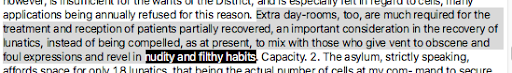

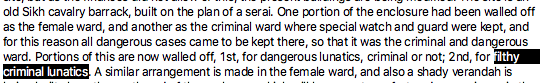

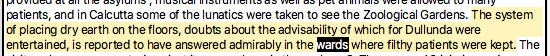

Swartz has also noted how vulnerable the insane were in a time where there was practically no prospect for a cure or appropriate treatment: ‘they had no place in the economic machinery of colonialism’; and when the subject was to be considered recovered, it was in very narrow terms of what a healthy mind represented, with productivity and obedience as evidence. As it turns out, being filthy brings out a lot of difficulties for the colonial utopia of a productive institution. The first one is that they require to be segregated from others. They even got to have a designated ward, alongside that dedicated to the infected with tuberculosis (see fig. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3. Examples for the urge for special accommodation for the ‘filthy’.

Fig. 3. Examples for the urge for special accommodation for the ‘filthy’.

![]()

Fig. 4. ‘Filthy’ patient’s wards in the classification of spaces.

Fig. 4. ‘Filthy’ patient’s wards in the classification of spaces.

The ‘filthy’ patients must be kept as separated as possible from the productivity chain, which serves as a means to evaluate the patient. The criminal lunatic, for instance, is regarded as an advantage because they are ‘useful’. Considering this model, the ‘filthy’ patients would be the least to be close to any kind of ‘recovery’, at least in the terms the colonizers imposed.

![]()

Fig. 5. The ‘criminal lunatic’.

Fig. 5. The ‘criminal lunatic’.

Another characteristic of the ‘filthy’ habit is its relation to the spread of diseases. Here, what is relevant is the need to pass the blame to someone who can not defend themselves, and for the authority in charge to remain guiltless and not be obliged to take further action and think about an alternate solution. As Swartz has noted: ‘The mentally ill, by virtue of their insanity, were not governable; colonial officials were’. The authority then had to follow recommendations and improvements to achieve a ‘successful’ facility. The number of deaths and diseases was to be accounted for and explained. One reasonable way to leave doubts of competence would be to expressly point to the ‘filthy patients’ (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The ‘filthy’ habit is often responsible for health problems.

Fig. 6. The ‘filthy’ habit is often responsible for health problems.

The observation of habits was done invariably to the advantage of the dominant class as enough evidence to suggest and legitimize certain colonizing fantasies. Habits are hard to break; but if the possibility of breaking them exists, the colonizer would be the one to take upon this task and pat himself on the back for his accomplishment. The colonizer, in his role of morally gifted and, in this case, an authority over the mentally differentiated, needs for his moral cause to be sufficiently challenging but not completely hopeless. However, the existence of the filthy patients shows to be a continuous reminder of the irremediable. Their filthiness lays not in the fact that they are dirty, but that they habitually display the impossibility of ruling over bodies who only answer to their individual nature. They are truly ungovernable and thus, the reports fail to describe them. They escape from the tidiness and clean typewriting of the supervisor in turn.

Fig. 7. The ‘filthy’ vs. the perfectly clean.

Fig. 7. The ‘filthy’ vs. the perfectly clean.

How to move forward after colonization? Muktesh Daund makes an interesting point for thinking about the history of mental hospitals in India and how the British conception of the lunatic asylum, a place where the mentally ill were to be separated from the community, had consequences beyond the end of the colonial era. European philosophy continued to influence the development of psychiatry in India in many ways, even if these methods were often an ill fit for India’s own socio-cultural context. For that reason, Daund’s final proposition for the future is to ‘evolve as a truly indigenous approach to mental health’. Perhaps then, the ‘filthy’ habit would be just a matter of getting dirty, no prejudiced connotation given, and definitely not a term for segregating an entire class of people.

Works Cited

Daund, Muktesh, et al. ‘Mental Hospitals in India: Reforms for the future’. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 60, no. 6, 2018, p. 239. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A526508346/AONE?u=ed_itw&sid=AONE&xid=29333b0b. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020.

Coleborne, Catharine. ‘Institutional case files: Insanity’s archive’. Sources and Methods in Histories of Colonialism: Approaching the Imperial Archive., edited by Kirsty Reid and Fiona Paisley, 1st ed., Routledge, 2017, pp. 119–134. discovered.ed.ac.uk, doi:10.4324/9781315271958-8.

Mills, James. ‘The Mad and the Past: Retrospective Diagnosis, Post-Coloniality, Discourse Analysis and the Asylum Archive’. Journal of Medical Humanities, vol. 21, no. 3, 2000, pp. 141–58. Springer Link, doi:10.1023/A:1009026603492.

Scull, Andrew. ‘Asylums: Utopias and Realities’. Asylum in the Community, by John Carrier and Dylan Tomlinson, Routledge, 1996, pp. 7–16. www.taylorfrancis.com, doi:10.4324/9780203359983.

Swartz, Sally. ‘The Regulation of British Colonial Lunatic Asylums and the Origins of Colonial Psychiatry, 1860–1864’. History of Psychology, vol. 13, no. 2, 2010, pp. 160–77, doi:10.1037/a0019223.