By Eduard Gafton

Figure. 1: Photograph of Women and Children Bathing at Vanarasi (previously Benares) - Source: British Library

In the first half of the 19th century, the British India system of medicine was essentially male-oriented and male-dominated; the primary areas of concern being the army, the jails, and the hospitals. (Mukherjee, Case-Study, 1883) This began to change somewhat with the advent of the first direct state intervention adressing Indian women’s health, through the form of the Contagious Disease Act (1868), which required sex workers to register and to subsequently be subjected to ‘different kinds of crude and obnoxious medical examinations.’ (Mukherjee, Gender) My study, then, treats this monstrous act as the starting point for analysing the emerging (if invisible) role women would take up in India’s medical system up until and well into the 20th century.

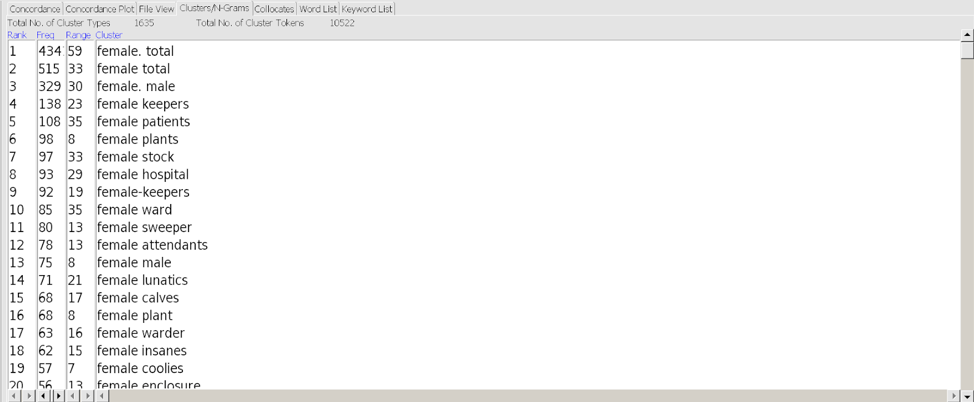

In terms of how my research has been conducted, I have started by using AntConc to track what words and or phrases prop up next to ‘woman/women’ and ‘female’, respectively. However, as I made my way through the results, I have eventually realised that one of the inherent faults of my approach is that zigzagging through the vast body of reports provided by the National Library of Scotland (NLS) will not and did not allow me to track the chronological evolution of women’s role in tackling diseases. As such, my solution was to base this study around the chronology of my search and refer to two select readings for a historical timeline and in order to corroborate my findings.

What Did British India Say About Indian Women?

Figure. 2. “Cooking Indian Style” - Source: University of Minnesota Libraries

I started off my research by looking at how many words are associated with the word ‘female’, which has fortunately returned some interesting appearances from the get-go. However, on taking on these appearances one by one, I was disappointed to find that none of the concordance searches were particularly telling of the possible role(s) that women took up or were assigned. In fact, looking at the results for female plant/plants, for example, is how I realised that the reports were talking about the two types of ganja plants - male and female - more about which you can read here.

Figure. 3. My own search appearances for ‘Female’ in AntConc.

Having had no real success with AntConc, I have consulted with the secondary readings in search for possible explanations as to why female keepers, to pick just one, resulted in about the most appearances. It is then that I realised that the number of female patients attending hospitals, especially before but even after the Contagious Disease Act of 1868 was very low which, as Mukherjee writes (Mukherjee, Gender), ‘strengthened the view in different circles that Indian women were averse to treatment by male physicians.’ (For more on this, and in particular on the fate of Indian ‘Coolie’ women, click here.)

Furthermore, the more I read Mukherjee, the more I realised that female keepers, patients, hospitals and wards came up as a result of the female body finally coming under medical attention and scrutiny. (For more on gender disparity in hospitals, click here.) In fact, this attention was patterned on Western medicine which is itself constructed on top of women’s involvement in medical practises such as midwifery and nursing. All of this, says Mukherjee again, together with many Indian reformers as well as British observers and administrators arguing that they should not be ‘deprived of the fruits of Western scientific progress’ (Mukherjee, Gender), eventually resulted in the establishment of a group of educated women medics.

‘Female Doctors’

Figure. 4. Interior of a temporary hospital in Bombay during the bubonic plague of 1896-187- Source: Wellcome Collection

Upon returning to AntConc, I fired up the concordance search for ‘female doctors’ only to receive a measly seven appearances. (For more on descriptions of the female, click here.) Out of all of these, only one drew my attention since it was an excerpt of a report which detailed how females must be examined by female doctors, so therefore more or less in line with what Mukherrjee had been writing about. I then decided to go ahead and search for ‘female hospital’, which eventually led me to dig for ‘female hospital assistant’, which resulted in 29 appearances. From this I assumed that women were more likely to be assistants to the physician rather than the primary caregiver.

But, in fact, this assumption is entirely incorrect as the whole story is very different: Mukherjee wrote extensively on how women played ‘a central role in national health regeneration through their influence over hygienic conditions within the household, and also by understanding that professional medicine was supposed to act as the best guarantee of health in complicated situations.’ (Mukherjee, Gender) So, then, reading into it I found out that to be a woman in India meant to be the family’s caregiver, the role model in hygiene practices and, as medical care eventually professionalised, to become an important medical consumer.

When Doing Laundry Can Be Dangerous

Figure. 5: Brown wicker basket - Source: PickPik

After searching for female hospital assistants, many of my searches revolved around women’s occupations: I searched for matrons, nurses and eventually I landed on a search for ‘women employed’. This led me to a report which mentions that there is proof ‘between the manifestation of cholera and the condition of the water-supply.’ This report, then, makes the argument that the water-tanks at Seonee (now Seoni) and Nagpore (now Nagpur) were contaminated and that this is surely the cause for ‘the very remarkable excess of mortality from cholera, occurring in the course of two successive epidemics, among women employed in washing clothes in washing clothes in tanks.’ Now this was interesting in and of itself, but when looking specifically at cholera, as this was the disease named, I have found more evidence of this: a different report attributed the ‘great excess of mortality from cholera among women’ to the ‘domestic duty of drawing and washing clothes’.

These two findings are fascinating because they exemplify how being a woman meant taking up two conflicting roles at once: on the one hand, women were meant to protect their families and uphold good hygienic practices, and on the other, their ‘domestic duties’ sometimes meant that they were potentially exposing themselves (and others) to disease.

Would one role be more important than the other to them? And, if so, which one?

Works Cited

Mukherjee, Sujata. Gender, Medicine and Society in Colonial India: Women’s Health Care in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Bengal. Oxford Scholarship Online, 2017, https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199468225.001.0001/acprof-9780199468225-chapter-1 [accessed on 06 December 2020].

Mukherjee, Sujata. Women and Medicine in Colonial India: A Case Study of Three Doctors in Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress, vol. 66, 2005-2006 pp. 1183-1193.