By Andrea Mejía

The collection of the Medical History of British India comprises several documents on mental health from the perspective of British health officials. An outstanding portion of the collection derives from the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission (IHDC), a group formed by orders from the British government in 1893. Four British officials and three “non-official Indian gentlemen” (Hall 1679) had a very specific purpose: find out whether cannabis caused mental health diseases and if it would be possible to tax hemp drugs.

The IHDC gathered 1,193 statements from witnesses, where they found no solid evidence to support cannabis as a cause of insanity (leaving aside hereditary diseases or preexisting conditions that would be enhanced by drugs). Most of the “evidence” came from rumours regarding the effects of smoked cannabis. However, to support the taxation and regulation of hemp, either as ganja or other presentations, such as bhang and charas, British authorities sustained their findings with a particular dichotomy: “Moderate” vs “excessive” hemp consumption.

At first sight, it seems that this clarification could be even considered as one of the first steps into contemporary laws on drug regulation. Nonetheless, AntConc analysis of the IHDC documents of the Medical History reveals that the commission’s justification relied on positive and negative opinions around hemp to shape a discourse of morality that linked approval and benefits with “moderation” and disapproval and detriments with “excesses.” In other words, the Commission did exactly what doctors and the Indian society had done before when admitting people to mental asylums due to “ganja insanity” because of rumours and social stigmas; they only transformed the society’s discourse into an ambiguous moral dichotomy for economic purposes.

A “beneficial” drug?

Before starting my analysis, it is worth defining the usage of the terms “positive and negative” for the adjectives and underlining the need to classify them under these two categories to understand the moral connotations in the following reading and interpretation of the AntConc results. With “positive,” I refer to all those words that denote approval, praise, or high quality, whereas “negative” refers to words suggesting disapproval, pejoration, or low quality, both of them from the perspective of the speaker. Throughout this analysis, I will center on how adjectives related to moderation and excess are nuanced with either positive or negative connotations to reflect the arguments on which the IHDC based their discourse to support cannabis taxation.

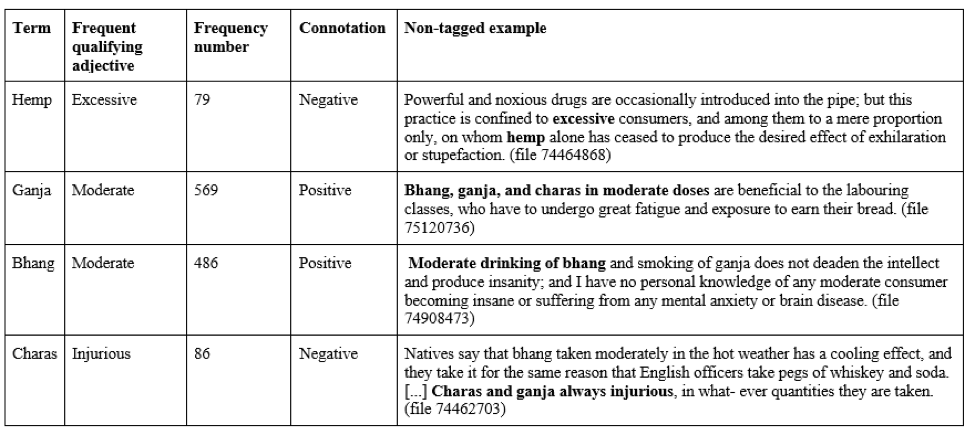

The analysis required Part-of-speech-tagged (POS-tagged) and non-tagged files of the IHDC archives and a collocates research of the terms that appeared the most with the words “hemp,” “ganja,” “bhang,” and “charas.” These words are mainly tagged as nouns (NN and NNP). Therefore, to find their moral connotation, the first AntConc search centered on extracting positive or negative adjectives related to hemp consumption, as well as the frequency of these adjectives. The results were the following:

We can notice from these first examples that the positive or negative quality of the adjectives describing hemp, ganja, bhang, and charas is connected to the degrees of consumption. In this sense, the frequency rate of positive and negative adjectives reveals that the comparison between moderation and excess was a key factor in the decision to regulate hemp and not ban it or validate it as a reason for admission into mental asylums.

However, there seems to be an apparent contradiction among different instances where words such as “beneficial,” “moderate,” or “injurious” appear. The case of the word “charas” is especially outstanding, as it also includes a comment on bhang and ganja. In this sentence, the speaker argues against hemp in general, except for bhang, by stating that the use of these drugs is not beneficial in any doses. This statement might seem to be contradictory to the IHDC’s final resolution to approve hemp regulation. Nonetheless, part of the IHDC’s evidence to dispel the belief of hemp as an inherent cause for mental health diseases were opinions themselves.

The “injurious” consequences of prohibition

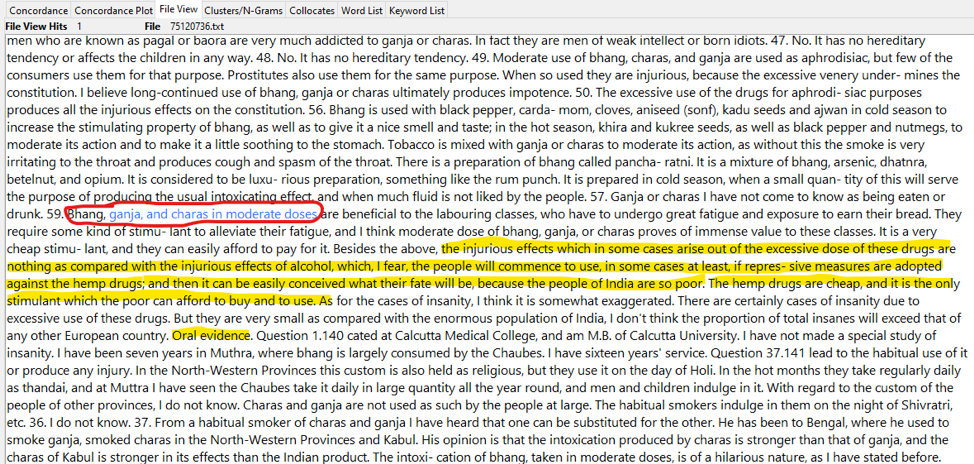

With the same AntConc research for hemp-related words, we find the following passage in the file 75120736 (see figure 1):

Figure 1: AntConc capture of file 75120736 “Indian Hemp Drugs Commission. Vol. V. Evidence of Witnesses from North-Western Provinces and Oudh and Punjab Taken before the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India. 1894.”

In this section of the files, we can find both positive and negative adjectives referring to the benefits of “moderate” consumption and the perils of “excess.” This is an example of the “oral evidence” that the commission collected to sustain hemp regulation. We can notice this in the intervention of a first-person speaker and verbs expressing opinions such as “I fear” in the highlighted section as well as the assumption that hemp helps calm workers and prohibiting it might lead them to the “injurious effects of alcohol,” especially because that is the only drug the Indian population can afford, according to the report. Ironically, we can notice with these details that the commission relied on the types of unsustained arguments they wanted to deny to support the benefits of regulation.

Moreover, an analysis of the context where these words appear also displays a concern for the purposes of consuming the drug. For instance, bhang’s qualification as “beneficial” derives from its alleged healing properties. Furthermore, according to the IHDC, bhang also had an important role in some religious ceremonies in India1. In this regard, I would like to emphasise the multiplicity of authorial voices in the files and how it creates a convenient ambiguity for the IHDC’s goals. In their article “Colonialism’s Civilizing Mission: The Case of the Indian Hemp Drug Commision,” Shamir and Hacker state that two of the three Indian members of the Commission were against the regulation of cannabis and attempted its prohibition by trying to prove that the commission’s alleged respect to India’s cultural traditions was but a construct (440). These members, Raja Soshi Sikhareswar Roy and Lala Nihal Chand, supported their argument by showing that neither of India’s religions with the highest number of followers (Hinduism, Islam, and Sikhism) approved drug consumption for spiritual purposes, so it was likely that the British authorities and “ganja smokers” were actually making up these Indian customs (453).

The IHDC gathered an eight-volume collection of “evidence” to discard hemp as a cause of mental health diseases. However, in the ambiguity of their statements and in the biases of the opinions they compiled, we as modern readers can see that the Commission was not likely to have used the same scrutiny to discard beliefs on hemp for the sake of their own economic purposes. AntConc has been a key tool in the task to see the ambiguous dichotomy of moderation/excess in the 1193 testimonies of the IHDC. Even if an investigation as that of the Commission managed to lay the groundwork for modern drug regulation research and laws, the study of the repetition of words and terms in a wide corpus can help us see that there might be other intentions beneath an archive’s surface.

Works cited

Hall, Wayne. “The Indian Hemp Drugs Commision 1893-1894.” Addiction, 114. Society for the Study of Addiction, 2019, pp. 1679-1682.

Shamir, Ronen and Daphna Hacker. “Colonialism’s Civilizing Mission: The Case of the Indian Hemp Drug Commision.” Law & Social Inquiry, Vol. 26, No. 2, Spring, 2001, pp. 435-461.

1 The AntConc analysis showed that the POS-tagged word “worshipping” had a frequency of 79 in relation to the word “hemp.” In this sense, we can see that another of the “moral” reasons to support hemp regulation had to do with the idea of advocating “prudence in the treatment of a cultural other” (Shamir and Hecker 460), which the British Empire allegedly followed as part of the moral code that ruled their colonization campaign (436).