By Cherie Bradley

‘Like material archives, digital ones are defined as much by the objects within them as by those that are not’ (Roopka Risam 48).

Thanks to the meticulous record-keeping contained within the Medical History of British India, there is a great deal related to the management of disease, disease control, public health and medical research between 1850 to 1950. The collection records landmark discoveries in medical research by famous scientists (Millard 24). One notable breakthrough is microbes and how they exacerbate the spread of disease (Millar 24).

The intricate collection of notes on scientific discoveries contained within the records are missing a vital piece. Despite the carefully crafted details in the collection, there is little mention of the experiences from the perspectives of indigenous people of India. The records are written from the perspective of British colonialists. Exploring the documents allows for some of our own breakthroughs and discoveries in unearthing untold narratives.

A note from the report The History of the Plague Administration 1886 reads ‘The Hindus, no longer fearful of measures which they neither understood the value of nor perceived the use, gradually accepted both treatment and segregation. The collector had meetings with the Mohomedians and gave them four Lady Doctors, and the Mohomeden Physicians, thus gradually gaining their acquiescence to these measures’.

This excerpt in the report depicts an instance of resistance from people of India, identifying them by their beliefs. The reports suggest that Hindus gradually accepted the medical measures administered them, largely because the colonists granted them women doctors. The colonists appear favourable and meet the needs of the culture and beliefs by providing female doctors. However, the author of this record presumes they know how the Hindus perceived the ‘treatment and segregation’ imposed on them. They depict compliant colonised subjects that did not initially agree to treatment willingly because they did not understand it. There is no evidence recorded here to support the claim that the Indian people lacked understanding of the treatment and measures administered. Also, there is no mention of force in this instance but it is implied in the measures of ‘segregation’ imposed on the people of India who showed reluctance to this treatment.

The report shows us the colonialists dealing with the obstacles presented to them by the indigenous people and not the experiences of the people who received treatment. According to Roopka Risam, a scholar in the field of archival research, the records of British India play a pivotal role in resurrecting a lost history (47). ‘Among postcolonial approaches to digital humanities’ Risam cites, ‘there are significant opportunities to develop digital archives that remediate colonial violence, write back to colonial histories, and fill gaps in knowledge that remain a legacy of colonialism’ (47). There are ways that we can explore the text from a distance to understand the accuracy of this narrative of a compliant and ‘gradually accepting’ indigenous people of India.

The records in the Medical History of British India are meticulous and detailed which suggests that they are an all-encompassing collection of India in this period. However, considering Risam’s point, it is important to consider that whilst the records present a great level of detail we must consider them a fragment of a larger landscape they are many untold stories during this time.

Illustrating the absence of information might seem like an impossible endeavour. Fortunately, the collection presents a lot of detail to aid in this task. By comparing the vast information contained within these records, we can attempt to illustrate the movement beyond the reports. One option is surface reading. A useful definition can be found from Laura Klein in her article, 'The Image of Absence', 'surface reading is a set of critical practices that emphasize attending to the materiality of the text and the structure of its language as well as to the critic's affective or ethical stance toward the work' (666). A critical practice exploring the collection from a distance such as searching for commonly used words in the report will aid in unveiling new discoveries.

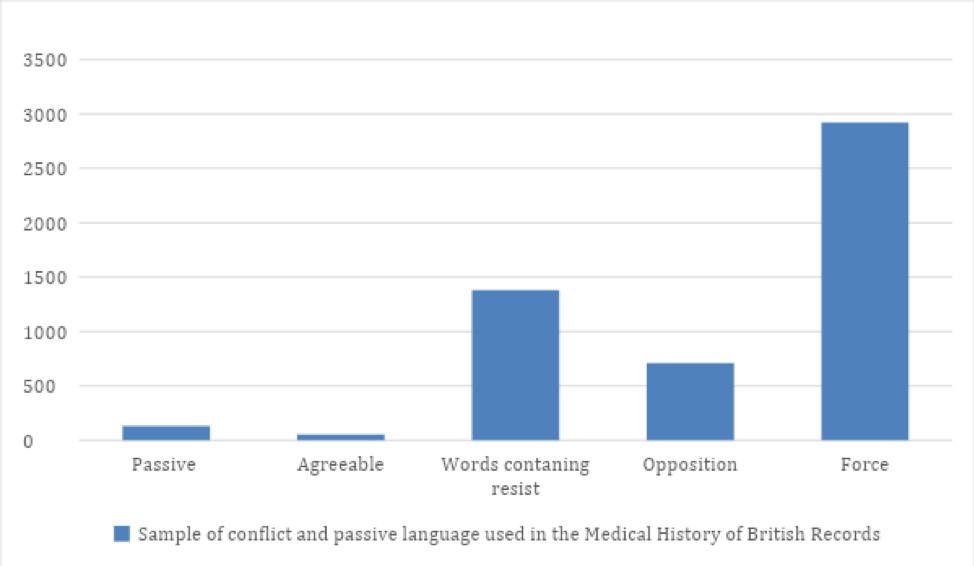

See figure 1 exploring and comparing a sample of the language used in the Medical History of British India collection. This graph visualises the opposition to the idea that the indigenous people of India are ‘gradually accepting’ of the medical measures administered by British colonists.

Figure 1

The words 'resistance' and 'opposition' are high in comparison to 'passive' and 'agreeable' suggesting that there is a degree of resistance to authority. This alone outlines the voices of the indigenous people as it suggests that the occupation of India by Britain was not as well received by some of the local people.

These are medical records so the expectations might be that resistance is not significant and perhaps would be recorded elsewhere i.e in an archive related to crime and punishment. But then why would the word 'force' need to be used so frequently in a medical setting?

What is also noticeable is the word 'force' appears often in the archives in comparison to agreeable and passive and yet closer reading in the example of the first except from the reports, the population of India are reported as 'gradually accepting' treatment from colonialists as if its was just time that eventually led them to believe the measures were acceptable to them.

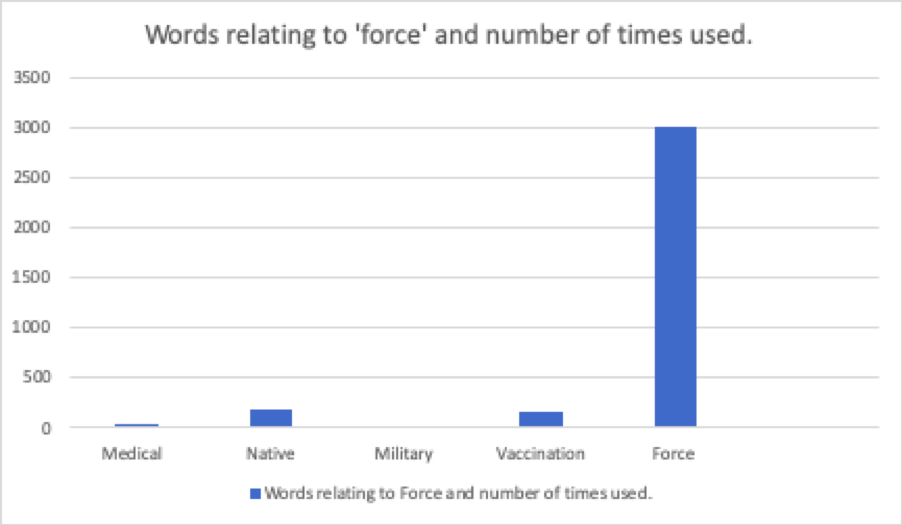

It is important to note the dangers of surface reading as it relies on the number of times a word is used, isolating it from the related context and potentially subverting its meaning. However, there are ways to mitigate this by understanding how often 'force' is used in frequency with other words, pairing it with its more significant context.

Figure 2

Few words stand out as frequently used in conjunction with the word ‘force’. Notable related words are 'British', 'native', ‘military’, ‘vaccination’, and ‘medical’. They appear often but not high in comparison to the number of times the word is mentioned (approximately three thousand times). It is an insidious word in the records suggesting that force is connected to many things contained within the records. Force has a significant presence during these times as it is detailed throughout the records and is used frequently in conjunction with many other words to ensure suppression of opposition.

Another way of understanding the texts as Klien mentions, is the critical practice of understanding the ‘ethical stance’ of the curator of the text and we know in this work that it is colonists. The Medical Records of British India, recorded from the perspective of colonialists logging their research is a form of curation. The language and content of the medical records demonstrate the element of decision making and curation that goes into record-keeping, highlighting bias contrary to the appearance of the bureaucratic 'functioning' language used throughout the records.

By highlighting resistance and opposition we unearth a voice of the voiceless. By understanding that the people of India at this time resisted treatment British colonial rule, we can begin to see that there is a separate voice to the ones presented in the archives. There was the need to use force therefore there were people that did not want the treatment. There was resistance based on religious beliefs such as Hinduism.

The archives of the now digitised files of the Medical History of British India, held at the National Library of Scotland, allow us to explore all the instances of recorded resistance. This is not something afforded to us solely from a close reading of the reports. Surface reading allows us to get a picture of the resistance in comparison rather than relying solely on what was carefully recorded. It is useful to explore the archives for the information contained within but we get a different perspective when we look for the missing information, in this example, the voices of the colonised as they tried to resist the treatment in some instances due to religious beliefs but as Risam mentioned, the records are a piece of a larger colonial puzzle rather than an all-encompassing viewpoint.

Works cited

Klein, Lauren F. ‘The Image of Absence: Archival Silence, Data Visualization, and James Hemings’. American Literature, vol. 85, no. 4, 2013, pp. 661–88. Silverchair, doi:10.1215/00029831-2367310.

Millard, Francine. ‘Of Microbes and Men’. Medical History of British India National Library of Scotland, 12 July 2020, www.nls.uk/media/769389/discover-nls-16.pdf

Risam, Roopika. New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy. Northwestern UP, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp 55-47. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ed/detail.action?docID=5543868.