By Molly Herbert

For millennia, religion has been at the core of the human experience. It seems to provide us with some degree of existential footing that grounds our sense of reality and helps us make sense of our place in the world. When it comes to Romance in Marseille, religion acts the same and, when put on a map, the places where the divine is referenced reflect the function or nature of the space a character is in. Ultimately, this novel seems to be about the reclamation of religion in Black communities from the white colonialists contrasting the hollowing of Christianity in White communities in order to retain systemic control.

The data mined for my project concerned salient religious themes and iconography and found itself largely dominated by Christianity despite the passing references to its Abrahamic siblings (Judaism and Islam). This is unremarkable given Christianity was the driving force behind the slave trade, and this is a book concerning the African diaspora, but it is nonetheless a distinction worth making. When cleaning up the results, I decided to remove entries that used ‘God’ or ‘hell’ as an intensifier as I wanted to map places where religion was thought about, not instances where a character is venting.

Link to Google Maps with markers mapping each instance where religion is referenced. The second layer consists of polygons that expand over every possible place where a relevant, mapped place in the novel could be.

What the mapped places symbolise is the spiritual function of the spaces created. By place, I am referring to a geographic point whereas with space, I mean the abstract social, emotional world created around that geographic point via interaction (de Certeau).

It’s particularly striking to me that there are three places that have multiple functions associated with them, those being Ellis Island Immigration Hospital, the Tout-va-Bien café and the Terrace on which Aslima has a vision about her upcoming death (113). Ultimately, this data could reflect the movement of spiritual ideas across place.

New York

The reader’s journey with Lafala starts in New York with the protagonist laid out on an Ellis Island Immigration Hospital bed (56). The location itself was simple to find as the island processed migration into the USA and offered comprehensive healthcare to the thousands of cases they received annually (Bridgeman Images; United States et al).

The dominant religious symbol there was that of an ‘Angel’ with 24 hits, followed by ‘Heaven’ with 8, and the other nouns and adjectives only featuring once or twice. Immediately, this summons to mind concepts of peace and help, and it is of interest to note that ‘Angel’ is the sole religious feature of Black Harlem. This is also representative of the prominence of the character nicknamed Black Angel, the adjective used to mark his function as a saviour (in Lafala’s eyes) as being different from the light-skinned stereotype. Indeed, it was the communities of Black Harlem that largely took in and housed migrants, just like Black Angel did for Lafala, and so the high frequency of this symbol represents the helping hand of the settled African diaspora towards those being processed on Ellis Island (Robertson et al).

The catch to this interpretation is that the noun ‘Hell’ is also featured in this dataset, and is only ever used again when describing the Prison Saint-Pierre – a place where Lafala is also confined due to his migrant status. The space created heals the flesh, but for migrants like Lafala who arrived as stowaways, it is also a reminder that without help from the law, this space represents the start of an incarceration or the disabling of their dreams if they are sent away.

Whilst I could not individually locate Black Angel’s House, the segregated area where Black and migrant residents lived was well documented and easy to find. Rather unfortunately, due to its reflection of the disproportionate incarceration of Black men in the United States, analyses of 1920-30s case files in New York’s Probation Department contained a wealth of data on African American addresses, jobs, family, marital status etc (Robertson et al).

The characterisation of the area as an ‘Angel’, with 11 hits in the database, reflects neatly upon the area’s communal culture before the Harlem Riot (1935) (Wilson). In particular, Black Angel’s own house parties are reflective of the rise of civil rights associations such as the ‘United Negro Improvement Association’ that organised social gatherings and trips for the community (69) (Robertson et al). The functions reflects a community spirit that helps others through and out of their struggles as a messenger of God would do.

Marseille

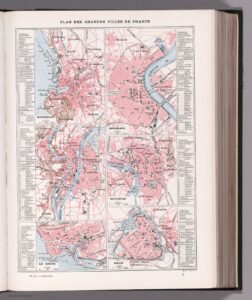

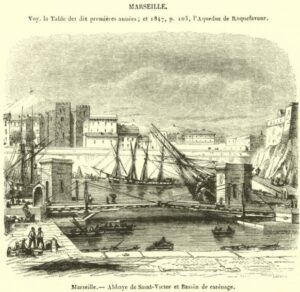

Both the Prison Saint-Pierre and the Cathedral have one clear religious function each and were both quite simple to locate given their descriptions and prominence on old maps. The Prison can be noted below as one of a collection at point 49 and the Church described as “high on the hill above Quayside” can be found at 29 given the terrain markers and old artistic images of the area (120) (Larousse; Bridgeman Images).

|

| Figure 1 – Plan des Grandes Villes de France (1990) |

|

| Figure 2 – Marseille: the old port with boats and over Notre Dame de la Garde (1903) |

The only trace of religious imagery inside the Prison is its metaphorical description as ‘Hell’ (156) and this can be juxtaposed by the only noun uttered around the Church being ‘God’ (120). The Prison seems to thus represent suffering under confinement whereas the Church functions as a place of divine control. Both institutions function as the enforcers of doctrine, whether that be theological or ideological, and it is the human body, whether it is Lafala’s or Aslima’s, that must restrict and contort to live within it.

Near the end of the novel, St Dominique is assisted in visiting the imprisoned Lafala by his school friend, Falope, who works at a West African trading company, and the space is suggested by the question “worship?” to serve the function of moral critique (128). I was able to locate this place given that one of France’s two major West African trading firms (CFAO) was founded in Marseille and there exist records of their headquarters (Milherou). Unfortunately, this source is a blog post and, despite offering a convincing history of the building, its sources are not properly linked despite claiming to be from official websites and historical online archives.

The notion of worship being situated outside a colonial company’s headquarters divorces the act from organised religion even if, in the Christian sense, God’s will was used to justify to theft of indigenous land in the first place. This is a fascinating angle given Claude McKay’s use of literary naturalist tropes throughout the novel (e.g. death of strong female character, Aslima) and the movement’s distrust of religion and preference towards science and tragic realism (Williams; Britannica). This space is shown to represent the replacement of God and dogma with apathy, profit and “clerical work” and appears to, antithetically to the beliefs of literary naturalism, question this shift as it leads to indigenous tragedy (128).

The Terrace whereupon Aslima had her religious vision took some time to find as there does not exist a perfect match to its description within Central Marseille. It overlooked a “bay” full of fishing boats, a “fifty f[oo]t” wall with a road below, a slope leading up to it, and a sandy area that children could play in (112). Figure 5 below fits the profile, with a sloped terrace at the right of the wall visible and the walkway around the sides on present day maps having been transformed into a main road.

|

| Figure 3 – Marseille, Abbaye de Saint-Victor et Bassin de carenage (engraving) |

Upon the Terrace, there are three uses of ‘worship’ and one of ‘God’, with the former concerning the worship of “The Sword of Life”, and the latter concerning African deities (114). Unlike at CFAO HQ, the notion of worship is not being questioned here but legitimised, and unlike at The Cathedral, the role of deities are not being focalised. This space is framed as the catalyst for Aslima finding her way back to religion and in doing so, it helps her rediscover her individuality and see the threat that is being posed to it by Titin.

The Tout-va-Bien cafe is the primary meeting place for most characters in the novel. Despite this, it was particularly difficult to locate, hence the wide potential area given to it on the map. The most likely area of Quayside for it to be located seemed to be the area touched by the retail quarter (see Figure 1). The data shown seems to show that class, race and migration in the cafe directly influences the spiritual thought plain.

Symbolically, ‘God’ is mentioned seven times and confirms the previous hypothesis that the Church’s space concerned divine control. In comparison, the three other themes are only mentioned once each and are ‘Angel’, ‘Hell’ and ‘Worship’ and function as the representatives of background issues. The first of these signifies the importance of the African American community internationally through Lafala’s affluent presence. Secondly, ‘Hell’ indicates that the sick and legally targeted make up a certain population given that only The Hospital and The Prison use term, implying that the cafe was a watering hole for the working and underclasses.

‘Worship’ in comparison to the vast amount more discussion of ‘God’, is predictably tiny. Worship is no longer a venerable act with the population of the Tout-Va-Bien using the literature to enact control over others as opposed to adjusting their lifestyles and habits to the reflect the expression of that belief system (90). This much is indicative of a white capitalist culture that has successfully gained control over society’s vulnerable to disillusion and disenfranchise. Given religion become a liberating factor for African Americans, this has large implications for the non-white population of the French storyworld (Williams).

Conclusion

Much of what constitutes being religiously active boils down to how faith is enacted and performed. Romance in Marseille is no exception to is, and provides a diverse, transatlantic account of how his world’s landscape is touched by contemporary religious trends. What the data most saliently highlights is the stark difference between how white colonialist capitalism replaced piety with profit and how the African diaspora embraced religion to help both them as individuals (e.g. Aslima identifying her threatened independence) and those suffering around them (e.g. Black Angel sourcing a lawyer for Lafala). Religious space is also racialized space.

Attached below is also a Canva presentation alongside an MP4 copy. The screenshots used are from the map above and are annotated to visually represent my interpretation of the Map. I found a strong limitation to using My Maps was the lack of customisation options for data presentation and the cramped grouping of the markers was not user friendly.

Mapping God in ‘Romance in Marseille’.mp4

Link to a Canva Presentation that visualises the map’s results.

Slide 1 – Black Harlem

Slide 2 & 3 – Ellis Island Immigration Hospital

Slide 4 – The Cathedral & The Prison

Slide 5 – CFAO Headquarters

Slide 6 & 7 – The Terrace

Slide 8 – Tout va Bien cafe

Work Cited

Bridgeman Images. Abbaye de Saint-Victor et Bassin de Carenage (Engraving). 1848. https://www.bridgemaneducation.com/en/asset/3644440/summary?context=%7B%22route%22%3A%22assets_search%22%2C%22routeParameters%22%3A%7B%22_format%22%3A%22html%22%2C%22_locale%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22filter_text%22%3A%22Abbaye+Saint-Victor%22%7D%7D.

Bridgeman Images. Immigrants at Ellis I[Sland]. [Date Unknown]https://www.bridgemaneducation.com/en/asset/2999572/summary?context=%7B%22route%22%3A%22assets_search%22%2C%22routeParameters%22%3A%7B%22_format%22%3A%22html%22%2C%22_locale%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22filter_text%22%3A%22ellis+island+hospital%22%7D%7D. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

Bridgeman Images. Marseille: The Old Port with Boats and over Notre Dame de La Garde. 1903. https://www.bridgemaneducation.com/en/asset/4794937/summary?context=%7B%22route%22%3A%22assets_search%22%2C%22routeParameters%22%3A%7B%22_format%22%3A%22html%22%2C%22_locale%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22filter_text%22%3A%22marseille+early+20th+century%22%7D%7D.

Editors of Britannica. ‘Naturalism | Realism, Impressionism & Post-Impressionism’. Britannica, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/naturalism-art.

Grant, Colin. ‘On the Waterfront’. The New York Review of Books, vol. 67, no. 17, 2020. www-nybooks-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2020/11/05/claude-mckay-on-the-waterfront/.

Larousse. Plan Des Grandes Villes de France (Marseille, Lyon, Le Harve, Bordeaux, Toulouse, Lille). 1990. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~267499~90042009.

Milherou, Dominique. ‘Cours Honoré-d’Estienne-d’Orves, Marseille’. Tourisme-Marseille.com, 2023. https://tourisme-marseille.com/fiche/cours-estienne-d-orves-marseille-restaurants-bars-galeries/.

Milherou, Dominique. ‘French Company of West Africa and the Crocodile, Marseilles’. Tourisme-Marseille.com, 2023. https://tourisme-marseille.com/en/fiche/french-company-of-west-africa-cfao-32-cours-pierre-puget-13006-marseille/.

United States, et al. Visitor’s Guide To Ellis Island | Alexander Street, Part of Clarivate. 1921.

→ Next Narrating Immobility in Time in Space