Introduction

This paper theorises drug markets through the concept of digital territory. I hypothesis that territorialisation is a critical process involving onshoring and binding the market as a virtual, bounded place.

The availability of controlled substances is mediated through two broad and interrelated distribution types. Social supply between friends and acquaintances relies on a moral economy of sharing and reciprocity (Coomber et al., 2016). Transactional commercial supply on the other hand emphasises profit and market mediate relationships, and sometimes validates predation and exploitation (Ancrum and Treadwell, 2017). New modes of drug distribution reshape both these distribution forms. One has been the emergence of online cryptomarkets. These are specialised markets hosted anonymously using the Tor network (Barratt and Aldridge, 2016). They present as shopfronts where vendors sell an array of drugs. Buyers pay using a cryptocurrency, typically Bitcoin, and the drug is delivered to them through the postal or courier system. Buyers are encouraged to leave reviews of the product and the vendor. Lively discussion forums discuss the quality of the drugs sold and the professionalism of vendors among other topics.

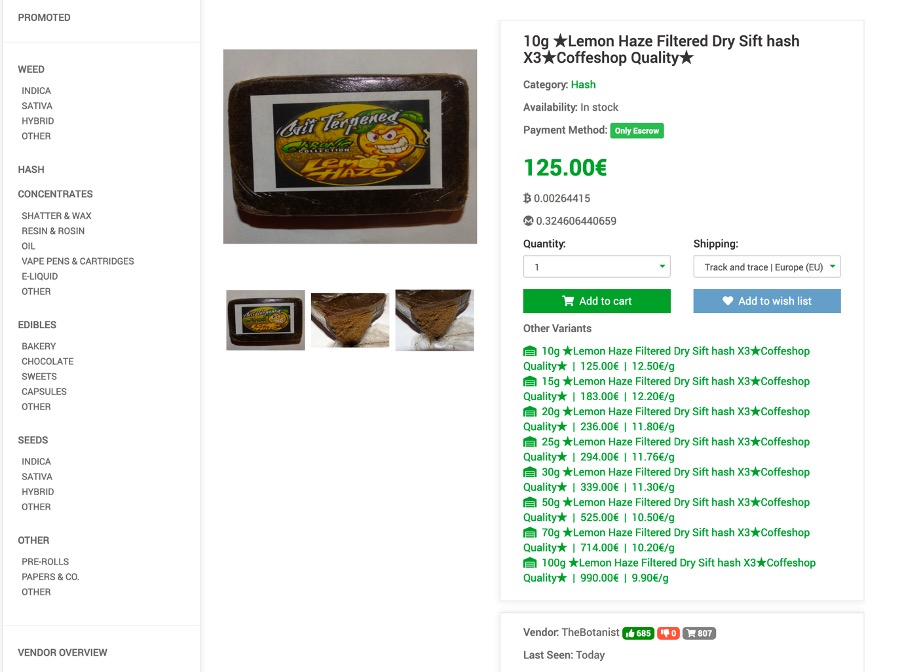

Figure 1 shows a listing from a market specialising in Cannabis. The listing typifies the way in which drugs are presented for sale. The vendor ships from Spain and offers shipping within the EU, and adds charges for express shipping. Discounts are provided for larger orders. Prices on this market vary in relation to the offline market. It is impossible to verify the content independently, however taken at face value some appear to be cheaper but many are higher priced, reflecting the ability of vendors to command more lucrative prices due to claimed higher quality (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2019). Higher prices may also reflect a premium for perceived safety of the buying process and quality of the product, demanding a comfort premium in addition to the normal risk premium paid for in illicit drug sales (Rhumorbarbe et al., 2016). Therefore we can see immediately that cryptomarkets promote particular kinds of market relationship between buyer and seller: a focus on quality, safety for both parties, greater choice and a tendency towards promoting high value, bulk buys (Aldridge and Décary-Hétu, 2014). Cryptomarkets are also the focus of methodological innovation. Due to their open design the cryptomarkets have facilitated the emergence of new digital trace methods to track changes in the drug markets such as the DATACRYPTO crawler (Décary-Hétu and Aldridge, 2013). These innovations allow for early notification of market changes such as the emergence of fentanyl and other novel synthetic opioids (Lamy et al., 2020).

The emergence and reach of cryptomarkets

Cryptomarkets emerged in 2011 with the launch of Silk Road on the Tor network. Its openness and anonymity signalled the arrival of a new type of drug diffusion (Aldridge and Décary-Hétu, 2016). After Silk Road was shut down in a law enforcement operation many other markets proliferated, sparking rounds of innovation and disruption between market administrators and law enforcement (Afilipoaie and Shortis, 2018). Disruption tended to demonstrate the resilience of the illicit drug market ecosystem (Décary-Hétu and Giommoni, 2017). Recent estimates put the cryptomarkets as a substantial but definite minority of the drug market overall, around €750000 Euro per day for sites serving European locations (Christin and Thomas, 2019). The Global Drug Survey records steady growth in use among its respondents, from 4.7% in 2014 to 15% in 2020 obtaining at least some of their drugs from darknet sites in the previous 12 months (Winstock, n.d.). Products sold range widely, with an emphasis on cocaine, cannabis, novel psychoactive substances, sedatives and stimulants. Most illicit drugs are available in some form but the product balance tends towards the ‘psychonaut’ user profile (Cunliffe et al., 2019). Alongside that there are many self-identified dependent and addicted users who find the predictability, professionalism and stability of supply a significant benefit (Bancroft, 2019).

The cryptomarkets are part of an ecosystem of messaging apps, webpages, discussion servers and social media platforms that service the drug market, mainly based in Europe, North America and Australasia (Moyle et al., 2019). They serve the end point of the global trafficking network, supplementing and sometimes replacing the trafficker to supplier/user stage (Dittus et al., 2017) and mostly supplying to consumer countries (Demant et al., 2017). Though sometimes depersonalised they are evolving and also provide the basis of dealer to buyer direct dealing (Childs et al., 2020). The cryptomarkets are best seen as one part of a larger flexible social and technological structure which facilitates rapid arrangement of deals between parties and expands the range of drugs sold. Drug sellers and buyers move around within it depending on the changing landscape and their specific requirements. This system generates an informal feedback loop allowing dealers to make more rapid decisions about what segments of the market to service.

Cryptomarkets are a focus for the gentrification hypothesis which suggests that a combination of long established social, economic and technical conditions is serving to reduce the importance of violence and predation in drug distribution. Drug delivery has displaced street or house based exchange in some circumstances, drug markets have become segmented by class and race, and the opportunities for combining drug dealing with other vice exploitation crimes has declined (Curtis et al., 2002). Cryptomarkets extend some of these developments, seeking to emphasise conflict resolution, cooperation and professionalism and punish predation (Martin, 2017; Norbutas et al., 2020), attractive to buyers and dealers (Martin et al., 2020). That may serve to reduce some of the harms of the illicit drug market (Aldridge et al., 2017) while at the same time concentrating risk and systemic violence among an already marginalised segment of the drug user population who have little access to drug delivery methods. While the cryptomarkets do put gentrification to the fore they also shift power in the marketplace and create new opportunities for vendors to develop exploitative or coercive strategies and techniques (Moeller et al., 2017).

Effect on purchase and drug diffusion

Cryptomarkets are designed in order to expose specific attributes of the drug being sold. Depending on the valued characteristics of the substance these might be the intoxication effect, texture, smell, appearance, potency, ease of titration, activity in combination with other substances, and pharmacokinetic behaviour. Generically these are referred to as quality, which means many different things to different users (Bancroft and Scott Reid, 2016). Whether and in what way the specific drug being sold is effective is the subject of extensive discussion on each market’s associated forums. The informational context is supplemented by the use of independent drug checking services by vendors and buyers. This can mislead and give users a false sense of security but on the other hand it normalises drug checking as an expected part of drug sale and consumption cycle (DoctorX, n.d.)

The impact is to foreground each drug being sold as a specific branded consumer product with pharmacological attributes that can be closely assayed. It draws on and brings together users’ cumulative experiential and subcultural knowledge, in common with other online drug user forums which examine not just the quality of each drug but what the drug is as a categorical object (Bilgrei, 2016). Behaviour is changed also. Easier availability may reduce temptation to hoard (Barratt, Lenton, et al., 2016) but the tendency towards vendors selling only in larger quantities may counteract that. The benefits of making large purchases means that purchases are often made with the intent of social supply (Demant et al., 2018).

Most users of the cryptomarkets are not novices and already have established experience in the face to face market. In the main they are attracted by predictable supply, choice and reduced risk. Users are predominantly male and young (Barratt, Ferris, et al., 2016). Some events such as COVID driven lockdowns have drawn large numbers of new users into the darknet (Barratt and Aldridge, 2020). Many new entrants just as quickly leave when they find the cryptomarkets do not suit their needs. Successful users need to learn and socialise themselves into the system to make it work to good effect.

Conclusion: The shifting territory of the digital drug market

The cryptomarket distribution system is a critical part of the move to drug distribution by delivery, whether through the postal system or tailored distribution services. They may be being supersded in technical prowess by well crafted custom build systems that use messaging apps (Power, 2020a, 2020b). As a whole set these systems bypass the face to face market and therefore are not immediately open to the kind of incidental interventions that harm reduction services may make. Having said that users often will be consuming at places where services may be present, such as raves and festivals but the rise of at-home delivery means that both distribution patterns and locations of consumption are changing. Consumption may take place much more at home, especially with the impact of COVID globally (Matheson et al., 2020). COVID has affirmed and extended existing inequalities (Chang et al., 2020) and the digital market has contributed to that. More affluent, better connected users have used their digital nous to continue drug consumption with little interruption. Those who do not have access to these distribution modes have been thrown back on a shifting and sometimes predatory street market. The impact of the darknet has to be seen in this context, as one component of an evolving social-technical infrastructure for drug distribution and consumption.

Bibliography

Afilipoaie A and Shortis P (2018) Crypto-Market Enforcement – New Strategy and Tactics. Swansea: Global Drug Policy Observatory.

Aldridge J and Décary-Hétu D (2014) Not an “e-Bay for Drugs”: The Cryptomarket “Silk Road” as a Paradigm Shifting Criminal Innovation. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

Aldridge J and Décary-Hétu D (2016) Hidden Wholesale: The drug diffusing capacity of online drug cryptomarkets. International Journal of Drug Policy 35: 7–15. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.04.020.

Aldridge J, Stevens A and Barratt MJ (2017) Will growth in cryptomarket drug buying increase the harms of illicit drugs? Addiction early online. DOI: 10.1111/add.13899.

Ancrum C and Treadwell J (2017) Beyond ghosts, gangs and good sorts: Commercial cannabis cultivation and illicit enterprise in England’s disadvantaged inner cities. Crime, Media, Culture 13(1): 69–84. DOI: 10.1177/1741659016646414.

Bancroft A (2019) The Darknet and Smarter Crime: Methods for Investigating Criminal Entrepreneurs and the Illicit Drug Economy. Springer Nature.

Bancroft A and Scott Reid P (2016) Concepts of illicit drug quality among darknet market users: Purity, embodied experience, craft and chemical knowledge. International Journal of Drug Policy 35: 42–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.11.008.

Barratt MJ and Aldridge J (2016) Everything you always wanted to know about drug cryptomarkets* (*but were afraid to ask). International Journal of Drug Policy 35: 1–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.07.005.

Barratt MJ and Aldridge J (2020) No magic pocket: Buying and selling on drug cryptomarkets in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and social restrictions. International Journal of Drug Policy: 102894. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102894.

Barratt MJ, Ferris JA and Winstock AR (2016) Safer scoring? Cryptomarkets, social supply and drug market violence. International Journal of Drug Policy 35: 24–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.04.019.

Barratt MJ, Lenton S, Maddox A, et al. (2016) ‘What if you live on top of a bakery and you like cakes?’–Drug use and harm trajectories before, during and after the emergence of Silk Road. International Journal of Drug Policy 35: 50–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.04.006.

Bilgrei OR (2016) From “herbal highs” to the “heroin of cannabis”: Exploring the evolving discourse on synthetic cannabinoid use in a Norwegian Internet drug forum. International Journal of Drug Policy 29: 1–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.011.

Chang J, Agliata J and Guarinieri M (2020) COVID-19 – Enacting a ‘new normal’ for people who use drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy: 102832. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102832.

Childs A, Coomber R, Bull M, et al. (2020) Evolving and Diversifying Selling Practices on Drug Cryptomarkets: An Exploration of Off-Platform “Direct Dealing.” Journal of Drug Issues: 0022042619897425. DOI: 10.1177/0022042619897425.

Christin N and Thomas J (2019) Analysis of the Supply of Drugs and New Psychoactive Substances by Europe-Based Vendors via Darknet Markets in 2017-18. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Analysis%20of%20the%20supply%20of%20drugs%20and%20new%20psychoactive%20substances%20by%20Europe-based%20vendors%20via%20darknet%20markets%20in%202017%E2%80%9318&author=N.%20Christin&publication_year=2019 (accessed 10 May 2021).

Coomber PR, Moyle DL and South PN (2016) Reflections on three decades of research on ‘social supply’ in the UK. In: Werse B and Bernard C (eds.) Friendly Business. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 13–28. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-658-10329-3_2.

Cunliffe J, Décary-Hêtu D and Pollak TA (2019) Nonmedical prescription psychiatric drug use and the darknet: A cryptomarket analysis. International Journal of Drug Policy. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.016.

Curtis R, Wendel T and Spunt B (2002) We Deliver: The Gentrification of Drug Markets on Manhattan’s Lower East Side: (530122006-001). American Psychological Association. DOI: 10.1037/e530122006-001.

Décary-Hétu D and Aldridge J (2013) DATACRYPTO: The dark net crawler and scraper. Software program.

Décary-Hétu D and Giommoni L (2017) Do police crackdowns disrupt drug cryptomarkets? A longitudinal analysis of the effects of Operation Onymous. Crime, Law and Social Change 67(1): 55–75. DOI: 10.1007/s10611-016-9644-4.

Demant J, Munksgaard R, Décary-Hétu D, et al. (2017) Going local on a global platform. A critical analysis of the transformative potential of cryptomarkets for organized illicit drug crime. In: International Society for the Study of Drug Policy, Aarhus, 2017.

Demant J, Munksgaard R and Houborg E (2018) Personal use, social supply or redistribution? cryptomarket demand on Silk Road 2 and Agora. Trends in Organized Crime 21(1): 42–61. DOI: 10.1007/s12117-016-9281-4.

Dittus M, Wright J and Graham M (2017) Platform Criminalism: The “Last-Mile” Geography of the Darknet Market Supply Chain. arXiv:1712.10068 [cs]. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1712.10068.

DoctorX (n.d.) Use and abuse of Drug Checking by cryptomarkets vendors | International Energy Control. In: Energy Control International. Available at: https://energycontrol-international.org/use-and-abuse-of-drug-checking-by-cryptomarkets-vendors/ (accessed 17 April 2019).

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, (2019) EU Drug Markets Report 2019.

Lamy FR, Daniulaityte R, Barratt MJ, et al. (2020) Listed for sale: analyzing data on fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and other novel synthetic opioids on one cryptomarket. Drug and Alcohol Dependence: 108115. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108115.

Martin J (2017) Cryptomarkets, systemic violence and the ‘gentrification hypothesis.’ Addiction 113: 797–804.

Martin J, Munksgaard R, Coomber R, et al. (2020) Selling Drugs on Darkweb Cryptomarkets: Differentiated Pathways, Risks and Rewards. The British Journal of Criminology 60(3): 559–578. DOI: 10.1093/bjc/azz075.

Matheson C, Parkes T, Schofield J, et al. (2020) Understanding the Health Impacts of the Covid-19 Response on People Who Use Drugs in Scotland. Scottish Government.

Moeller K, Munksgaard R and Demant J (2017) Flow My FE the Vendor Said: Exploring Violent and Fraudulent Resource Exchanges on Cryptomarkets for Illicit Drugs. American Behavioral Scientist early online(v). DOI: 10.1177/0002764217734269.

Moyle L, Childs A, Coomber R, et al. (2019) #Drugsforsale: An exploration of the use of social media and encrypted messaging apps to supply and access drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy 63: 101–110. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.005.

Norbutas L, Ruiter S and Corten R (2020) Reputation transferability across contexts: Maintaining cooperation among anonymous cryptomarket actors when moving between markets. International Journal of Drug Policy76: 102635. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102635.

Power M (2020a) A New Robot Dealer Service Makes Buying Drugs Easier Than Ever. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/jgxypy/televend-robot-drug-dealer-telegram (accessed 22 October 2020).

Power M (2020b) Online Drug Markets Are Entering a “Golden Age.” Vice. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/dyz3v7/online-drug-markets-are-entering-a-golden-age (accessed 22 October 2020).

Rhumorbarbe D, Staehli L, Broséus J, et al. (2016) Buying drugs on a Darknet market: a better deal? Studying the online illicit drug market through the analysis of digital, physical and chemical data. Forensic Science International 267: 173–182.

Winstock PAR (n.d.) Global Drug Survey 2020 Key Findings.: 11.

Figure 1, Cannazon market (10/6/2021)