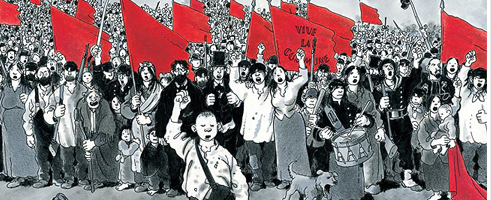

For the final session of a seven-month-long journey together, the group had asked people to prepare five-minute activities. I wanted to bring my excitement about Kristin Ross’s book Communal luxury: the political imaginary of the Paris Commune to the group, and brought along printed copies of an interview with the author about the work. I felt that in many ways, our course itself contained echoes of the imaginaries Ross discusses, sets of ideas and practices that emerged during the 71 days of the Commune and then were taken up and developed, including by Communards who escaped from the brutal repression into exile in various places, such as Élisée Reclus, and sympathizers including Karl Marx, Peter Kropotkin and William Morris.

‘Communal luxury’ is an odd pairing; the word ‘luxury’ invokes class divides, while the ‘communal’ aspect runs directly counter to such distinctions. As Ross points out, the term was not frequently used in Commune-related documents, appearing in the manifesto put out by artists and artisans. Ross sees it as ‘a kind of prism through which to refract a number of key inventions and ideas of the Commune’. She uses this prism to examine how the Commune and its inheritors go beyond utilitarian commitments to just ending the worst forms of exploitation and meeting bodily needs, to imagining ways of living and working that value beauty, enjoyment, intellectual exploration, solidarity and, crucially, the time and space for all of these.

The Communards and those who took up their imaginary felt that ‘public beauty’ should shape the environments in which we all live, work and play; that art is something we all can do; and that making shared environments is inherently creative. This implies that time and resources should be available for creating such environments, and they should be accessible to everyone. A related meaning is the idea that everyone can and should be both a maker and a thinker, with that sense of equality being embedded not only in work, but in how education and art are conceptualized and organized. Such a view breaks down the division between mental and physical work, and between high art and craft. An example of this is a Communard Ross writes about, Napoléon Gaillard, who called himself an ‘artist-shoemaker’ arguing that his work should be valued equally to that of artists working with words or paint.

Challenges to conventional boundaries are evident in those who transmitted the echoes of the Commune. Ross writes of Morris, Kropotkin and Reclus that all three ‘were socialized outside of the university, with its already hardening conception of disciplinary divides and quarrels pitting the competence of geographers against that of economists, or the competence of historians against that of sociologists… It is impossible to detect a will to specialization in their work. Instead, each of the three manifests an almost Balzacian ability to hold together multiple levels of a complex reality in such a tightly knit system of interconnection that failure in one sphere—say, the built environment, or education—is inevitably related to failure in another.’ This ‘holding together’ enabled a sensibility Ross identifies as being deeply ecological in conceptualizing human flourishing as necessarily embedded in nature.

I didn’t manage to hold anything together when I brought this idea to our session. My effort to convey what might be relevant about ‘communal luxury’ to what we had been doing was something of a failure. The text I had hastily printed out was missing pages, and so I read aloud a paragraph, but while reading, I realized that the text was very dense and people couldn’t really understand how it was relevant. I tried to explain, but found myself relapsing into didactic teacher mode. Cramming into a few minutes even the points I’ve noted above—which hardly do justice to the richness of the refractions in the book—was an impossible task.

For me, this experience reflected my occasional frustration with the few opportunities we found during the course to concentrate on exploring readings together, as well as the sense of never quite having time to engage as fully as we might. We are all deeply embedded in our different ways in the university as it is, rather than as it might be, and sometimes it is hard to imagine it otherwise. We are bombarded with readings and information relating to our silos of knowledge, and perhaps don’t have much energy left to explore.

Immanuel Wallerstein argues that disciplinary boundaries are intrinsic to the capitalist form of the university—they divide knowledge and block the extensive knowledge necessary to connect the dots in a world capitalist system. Our attention and analysis is concentrated on matters of limited scope, blocking the potential conversations that might challenge existing hegemonic understandings. At times in the course, we all discovered how little we know about the experiences and perspectives of other people in the same institution.

So the problem is: what are the readings that should ground the course? Is it realistic for everyone to read the same things? Jacotot and Rancière (see my previous post) apparently view this is an essential to learning; collective engagement with a text, through discussing what one sees in it, and listening to the views of others, is critical for ‘universal teaching’. But someone has to decide what text that is going to be. And we might spend two hours debating what we should read… and feel that we didn’t ‘do’ anything.

Questions have constantly arisen in the course about ‘what are we doing’ and whether we are ‘producing anything’. But what if learning occurs without ‘product’? Or what if the learning is about subjectivity, an act of becoming, a performance of something new and different, struggling to be imagined and struggling to be born in a space and time where capitalist logics give us little of each? At many moments, we did find time and space in the ‘cracks’, just as we managed to create this course at all. And there, I found traces of ‘communal luxury’.

Thanks for posting this Sophia, it’s very interesting to have a little more time to digest the text and ideas you wanted to share with us.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts! I find this idea of ‘communal luxury’ really interesting and something I’ve been grabbling with myself lately.

Hi Sophia,

I remember this session well and was intrigued both by the Paris commune and life within it. The frustration in not having enough time in the sessions to fully fledge our ideas I agree with. However, I feel like we have learned over the duration of the course and we have expressed this learning through our reflections and the time we spent in and outside of class discussing the course! Overall I have found these moments of ‘communal luxury’ rewarding throughout the course and enjoyed reading your reflection.