In 2017 I completed my Bachelors in Fine Arts, a degree which focused on visual literacy and representation through the work of the creative. In 2018 I embarked on a master’s in Historical and Heritage studies which focused on the experiences of Afrikaner women during the conscription of white Afrikaner men from 1980 to 1990. This dissertation explored the narrative of my family which is intricately linked to the Dutch Reformed Church, the South African Defense Force, and Apartheid. I was drawn to address the position of my family within a post-apartheid South Africa. Through the use of family albums and recipe books, I was able to uncover cultural practices that link directly to colonialism and slavery such as food making. My mentor Professor Siona O’Connell has been a magnificent inspiration in the work that I had completed since 2017.

The topic of the Dutch Reformed Church has surfaced in most research projects that Professor O’Connell and I have worked on since 2017. In 2018, we were approached by the SA Sendinggestig to research and curate an exhibit that would be implemented in the Long Street Sendinggestig Church building as part of their commemoration service. This research brought into focus the history of the Church in South Africa and its long-standing relationship to colonialism, race, and Apartheid. The building was erected in 1804 and dubbed the “Zuid-Afrikaansche Gesticht” (Hopkins and Le Grange, 1965: 216). On 22 April 2018, the church celebrated its 220th anniversary (Minnaar, 2018). Although this seemed like a celebratory moment, there is also a moment of unfinis

hed business to consider around this event. For one, it is estimated that three and a half million people experienced forced Removals between 1960 to 1982 under the Apartheid Government (Platzky et al., 1985). These evictions had led to the relocation of the congregants and in turn a downscale in attendance of the church. This project had prompted questions around racial segregation and the existing pain of being dispossessed. Questions raised during this project become all the more relevant when looking at Elandskloof as a case study.

Another project that had a significant impact on me was my exhibition “Pakkies aan Boetie” which I had exhibited in May of 2019 as part of my Master’s dissertation. This exhibit was based on the experiences of the mothers of conscripts who were sent to the border. As a way of communicating with their sons women would send packages to the borders along with letters. These packages had contained home-baked goods including troepekoekies and biltong (Niemand, 2019). The exhibit had changed the nature of my research by looking into the practices of making food and how this may contribute to a heritage that forms part of the South African narrative.

I would describe my approach as use of a combined form of methodology, one of Narrative Inquiry and the other of foodways. Narrative Inquiry according to Matti Hyvärinen “Narratives bring to the open rich, detailed and often personal perspectives.” (Alasuutari et al., 2008: 447) Social research has found a new interest in the stories and histories surrounding individuals. This interest in the narratives of individuals has been identified as the “narrative turn” in social research. Ivor F. Goodson and Scherto R. Gill discuss this turn in their article titled as The Narrative Turn in Social Research (2011) as “the narrative turn has emerged in the context of a new wave of philosophical discussion on the relationships between self, other, community, social, political and historical dynamics. It also includes questioning and challenging the positivist approach to examining the social world and understanding human experience.” (Goodson and Gill, 2011: 18). When I completed my Masters in Museum and Heritage Studies, I was reminded throughout my research the benefit that interdisciplinary research holds. My research has since taken form of many research traditions. The focus of most of my past research would fall under a Qualitative approach to research with a focus on Gender, Food and Memory.

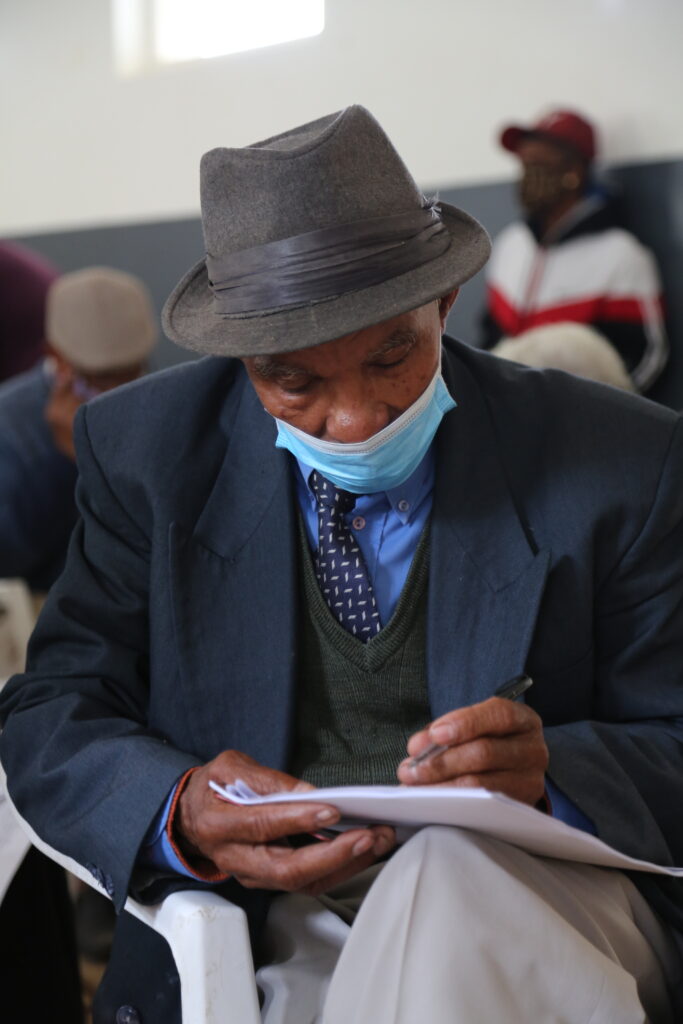

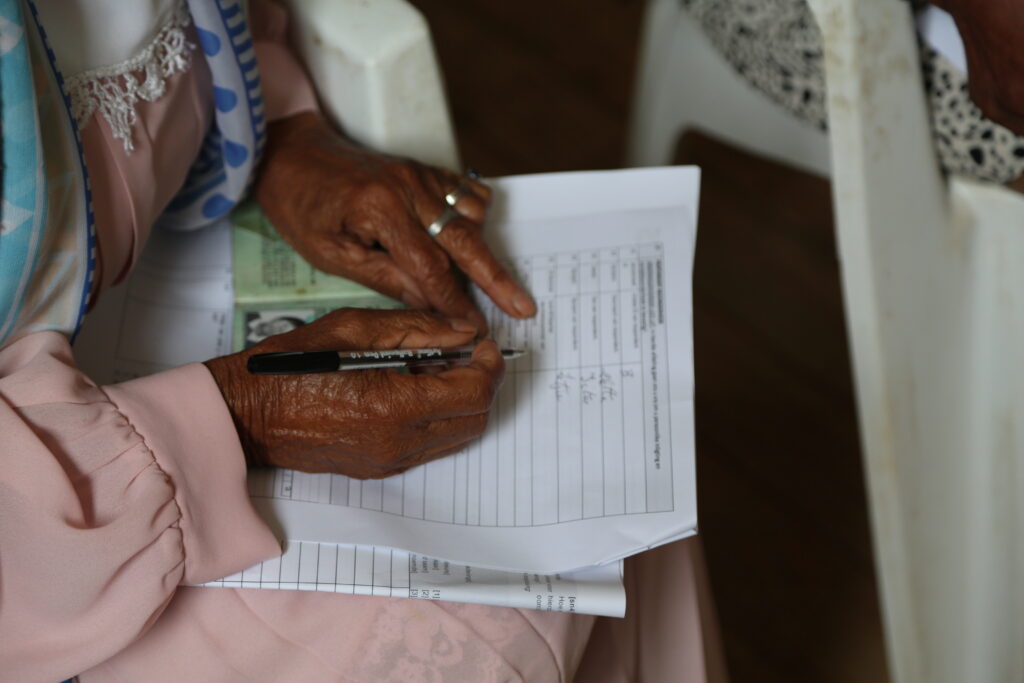

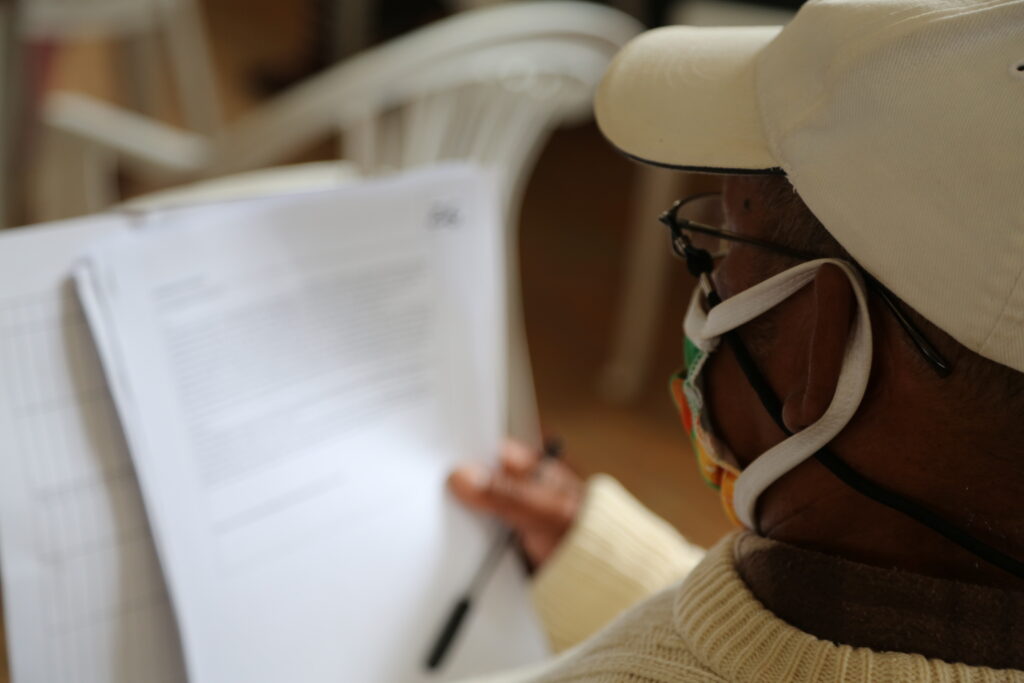

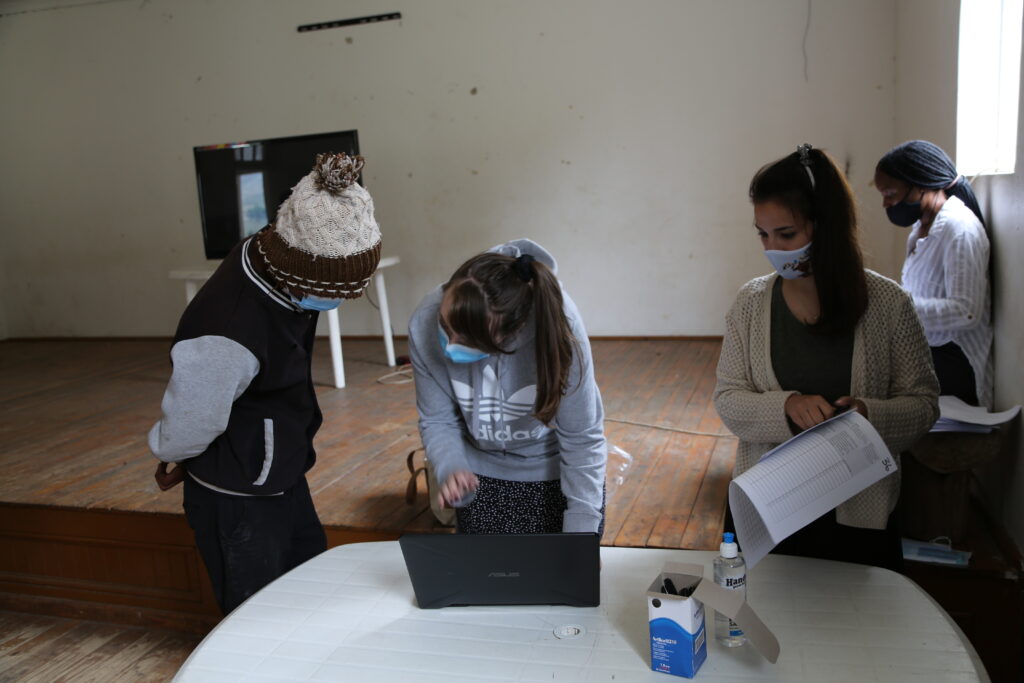

When we first started researching the historical injustice that surrounded the Elandskloof community, I felt like a voyeur looking into a sliver of the South African historical landscape. I must admit that the arm’s length research we conducted at the beginning was somewhat of a comfort zone, it allowed me to grapple with the challenging history without being confronted by it. It was not until I had arrived in Elandskloof, speaking with the Elandsklowers as part of our field research, that I had realised the biggest challenges still lie ahead. When we entered the space of Elandskloof, I felt like an outsider. It was not until we had opened up conversation around food where it left me with a feeling of familiarity. There was a sense of understanding that I felt with my mother and grandmother. The conversations with the women of Elandskloof reminded me of the importance of how certain dishes ought to be cooked and how recipes ought to be followed that was similarly instilled in me by my mother and grandmother.

Food, I would argue, holds the same power as images and objects; once consumed, they can evoke emotion and also memories (Brulotte and Di Giovine, 2014: 2). Urmila Jithoo recounts in her book titled: From the table of my memory (2005) “Meals are a time to conjure up memories of sights, sounds, tastes and smells and, sometimes, to summon the spirits of the past.” (Jithoo, 2005: 3). Most of my experiences with cooking took place in our home kitchen where my mother would show me how to prepare meals similar to how her mother had shown her when she was younger. Cooking thus becomes a gendered activity and one that is often handed down from generations of mothers. Gender within my research is understood as a cultural construct that is observed through the role of women in an historical context and how it is understood by generations of grandmothers, mothers, and aunts.

Sources:

Alasuutari P, Bickman L and Brannen J. (2008) The SAGE handbook of social research methods, London: SAGE.

Brulotte RL and Di Giovine MA. (2014) Edible identities: food as cultural heritage. Farnham, Surrey; Ashgate.

Goodson IF and Gill SR. (2011) The Narrative Turn in Social Research. Counterpoints 386: 17-33.

Hopkins HC and Le Grange PJ. (1965) Die moeder van ons Almal : geskiedenis van die Gemeente Kaapstad 1665-1965, Kaapstad: N.G. Kerk Uitg.

Jithoo U. (2005) From the table of my memory: food, friends, travel: a memoir with recipes, Lannsdowne. London: Double Storey ; Global [distributor].

Minnaar K. (2018) VGK SA Gestig vier ryke geskiedenis! Available at: https://kaapkerk.co.za/vgk-sa-gestig-vier-ryke-geskiedenis/.

Niemand, D. (2019). “Die Swakheid van Sommige”: Navigating race through Foodways of the women of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa. University of Pretoria.

Platzky L, Walker C and Surplus People P. (1985) The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa, Johannesburg: Ravan Press.