Guatemala: land of water and fire

Guatemala: land of water and fire

Cities on Volcanoes Conference

The twelfth edition of the biennial conference Cities on Volcanoes (CoV) was hosted in Antigua Guatemala, a city under the watch of three volcanoes: Fuego (active volcano named “fire”, and Kaqchikel in Maya), Agua (dormant volcano named “water”, and Hunahpú in Maya), and Acatenango (dormant). CoV brings together experts of a broad range of disciplines that work towards the best way to face the challenge of living on active volcanoes: from studying the science behind volcanic processes, to communicating the risk associated to these hazards, understanding social ties to the volcanic land of the communities cohabiting with these volcanoes, and the optimisation of the logistics of evacuation, displacement and emplacement of these communities during volcanic-related human disasters. My contribution to CoV12 consisted on presenting the work I’ve been doing for in my PhD so far, which is understanding the erosion processes in pyroclastic density currents (PDCs)[1], with the ultimate aim to improve the erosion modules in large scale models that are used to forecast the probability of volcanic hazards occurring populated areas around volcanoes.

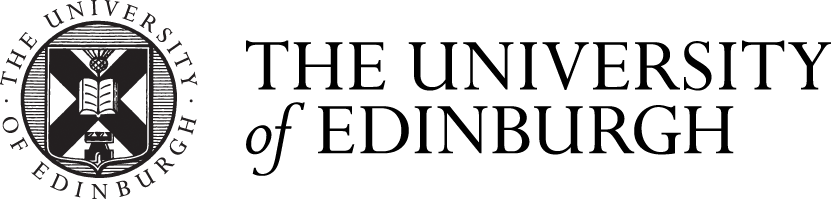

Figure 1: During the presentation in CoV12 about my PhD work.

This journey was incredibly nourishing for me. During the conference days, I had discussions with the scientists that have created these large-scale models, which inspired new ideas to develop in the next stages of my PhD. During the fieldtrips to Fuego, I got first-hand explanations about the eruption mechanisms and pyroclastic flow behaviour from scientists like Matt Watson and Sylvain Charbonnier. I also learnt a lot from the incessant and enthusiastic conversations between Eric Breard and Symeon Makris about pyroclastic flows and volcanic debris avalanches (and in general, about grains rolling!) during the bumpy chicken-bus rides up the volcano flanks. Also, from speaking to the people that dedicate their lives to volcano monitoring in the communities nearby Fuego, such as Don Gustavo Chigna from INSIVUMEH (National Institute of Seismology, Volcanology, Meteorology and Hydrology in Guatemala), who has witnessed over 70 eruptions of Fuego and has made his life endeavour the best understanding Fuego and the people who live around it. Most importantly, I’ve understood the complexity of the science surrounding volcanic risk: the natural processes are one thing, and the people are something completely different, and the best science one can do must take into account the people and how it’ll influence their future. This aspect has given my work a new dimension, and has sparked in me a very strong commitment to this field of study.

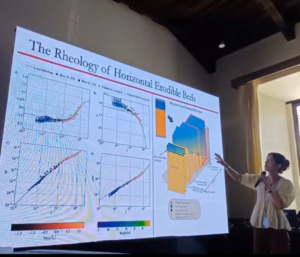

Figure 2: Me sitting on A’a lava in front of Pacaya volcano.

The 2018 Fuego Eruption: a turning point

Figure 3: COLRED volunteer in Los Yucales community, showing their evacuation documents.

Guatemala is home to 37 volcanoes, three of which are relentlessly active: Fuego, Santiaguito and Pacaya. The eruption of Fuego in 2018 was a human disaster that became a turning point in Guatemala in terms of volcano monitoring, risk communication and management. Over the years, Fuego has shown a baseline of low level of explosive activity, during which our friend burps every 10-20 minutes to release some bowel pressure, a process that the volcanologists call “degassing”. Every now and then, however, the eruptions become more violent, which was the case of the night of Sunday June 3rd 2018, where Fuego entered a paroxysmal stage[2]. On the night of the eruption, clouds hindered the visual observations of the volcanic activity. Furthermore, the only seismic station designated to record volcanic tremors that precede violent eruptions hadn’t been working for months, because the INSIVUMEH maintenance engineers had resigned due to the low wages allocated by the government. These conditions delayed the response of the authorities in charge of the evacuations. During the 2018 eruption, PDCs started flowing down an unprecedented route, over the south-east flank through Las Lajas Barranca (“ravine”). Throughout the hours of the eruption, several PDC pulses descended through Las Lajas in a controlled manner. This gave a false sense of security to some of the residents nearby, which made the evacuation an uphill job for CONRED (National Coordinators for Disaster Reduction), because people weighed the risk of the PDC lower than leaving their houses and cattle exposed to being robbed. The tragedy was unravelled by the last PDC pulse, which overflowed Las Lajas given that the channel had been filled up with the previous PDC deposits, flooding with boiling debris the nearby community of San Miguel los Lotes in a Sunday afternoon, when all the families were at their homes. This turn of events took the lives of hundreds of people.

This tragedy was a turning point that sparked several actions that have improved the response to volcanic eruptions in Guatemala. Firstly, funds were designated to the emplacement of a network of seismometers for the detection of precursive volcanic tremors used in early warning programmes. Moreover, evacuation logistics were developed in the nearby communities through the communication between INSIVUMEH, the CONRED and the COLRED (Local Coordinators within communities, see Figure 3), which are grounded on slow and steady work with the communities to build awareness of the hazards and trust to these authorities. Lastly, a new law was issued, which allows the CONRED to not be responsible of casualties that have decided to stay in a danger zone during evacuations, for the government had previously taken workers of CONRED to trial for that reason despite their tireless work to save lives on the 2018 eruption. A lot more progress is to be done here in Guatemala, but this is an example of learning from disasters and how to put lessons into action.

A land affected by multiple natural and social hazards

Guatemala has a rainy season from May through to November. Every afternoon heavy rain mobilises the loose volcanic material that is lying on the flanks of Fuego, and transports it in violent flushes down huge channels. These muddy flows, or lahars, are incredibly powerful, carrying boulders as big as cars, with speeds as fast as 40m/s! What is more, lahars can become boiling muddy rivers if the ash deposited at the top of the volcano is recent and therefore hot, reaching temperatures of several hundred degrees Celsius. The lahar channels are about 20-30m deep and are created as these flows cut through recent unconsolidated pyroclastic flow deposits (see Figure 4). However, after a few days these same ravines are filled up with lahar material, and the next lahars have no alternative other than to spill over the channel, occasionally reaching nearby communities.

Figure 4: Inside a lahar channel, part of barranca El Jute, during the dry season nearby the community La Reina.

Lahars are secondary volcanic hazards that pose an elevated risk to the vulnerable communities around Fuego. This is the case of the Colonia Las Palmas, located very close to the Barranca Ceniza (“ash ravine”). After a flooding disaster in July and October 2023, the government deemed the area around Las Palmas “uninhabitable”, and relocated these people to a big city called Esquintla. In their Colonia, their lifestyles consisted of owning a terrenito (“small patch of land”) where they worked the land and perhaps have some cattle, close to their families and safe from big city crime. When they were relocated, they were given a house but they had lost their means of living and their life style. This triggered the migration back to the danger zone. They not only cleared the whole village from the lahar debris, but they committed to relentlessly dig the lahar deposits from the barranca so that the lahars of the coming rainy season do not overflow and affect their Colonia again (see Figure 5). This shows the complexity of the risk framework around Fuego: volcanic risk is only another risk that local people weigh over other priorities, or rather, necessities.

Figure 5: Digger clearing old lahar deposits to avoid overspill in Barranca Ceniza during the next rainy season in Colonia Las Palmas.

A robust and accommodating strategy for displacement and emplacement of communities at high risk, whether it be lahar or PDC, is instrumental to draw these communities away from imminent disasters. As discussed in CoV12 by many scientists from social and geology backgrounds, this must be done with respect and understanding of the need of the people that cohabit with volcanoes. This applies from the science being done regarding hazard analysis and mapping, to risk communication, to the issuing of the evacuation and emplacement strategies. As a geophysicist working on a very numerical aspect of volcanic risk myself, this conference was a reminder that science cannot be detached from the socio-anthropological context with respect to solving problems. One of the messages that I take home came from an intervention in a discussion from the Colombian volcanologist Marta Calvache, calling for communication between scientists, sociologists and authorities: “science alone will not solve this issue”.

Figure 6: Children playing football in Colonia Las Palmas, now deemed uninhabitable.

* * *

Camino al revés

De vez en cuando

camino al revés:

es mi modo de recordar.

Si caminara sólo hacia delante,

te podría contar

cómo es el olvido.

Humberto Akabal

Bonus photo of a scene from a house in Colonia Las Palmas

[1] Pyroclastic flows are currents of gas with a dense underflow that can reach speeds of up to 200 m/s and are as hot as 700°C.

[2] Violent eruptive stage