Many visitors to Situated struggled to understand the concept of a “university art collection.” Most people assumed that it was composed wholly of student artwork, or only Scottish art, and were confused to learn about its broader scale.

This lack of public awareness of university art collections is described in a 2015 Times Higher Education article. Bluntly titled “What is the point of university art collections?” the article describes how “many universities inherit unexciting art collections put together at different times with no overall organising principle.”[1] While it is true that many university art collections—including Edinburgh’s—were historically acquired relatively haphazardly, recently many have developed specific collection development plans. How do university art collections approach collection development and engagement, and how do these projects sit within the broader institutions of which they are a part?

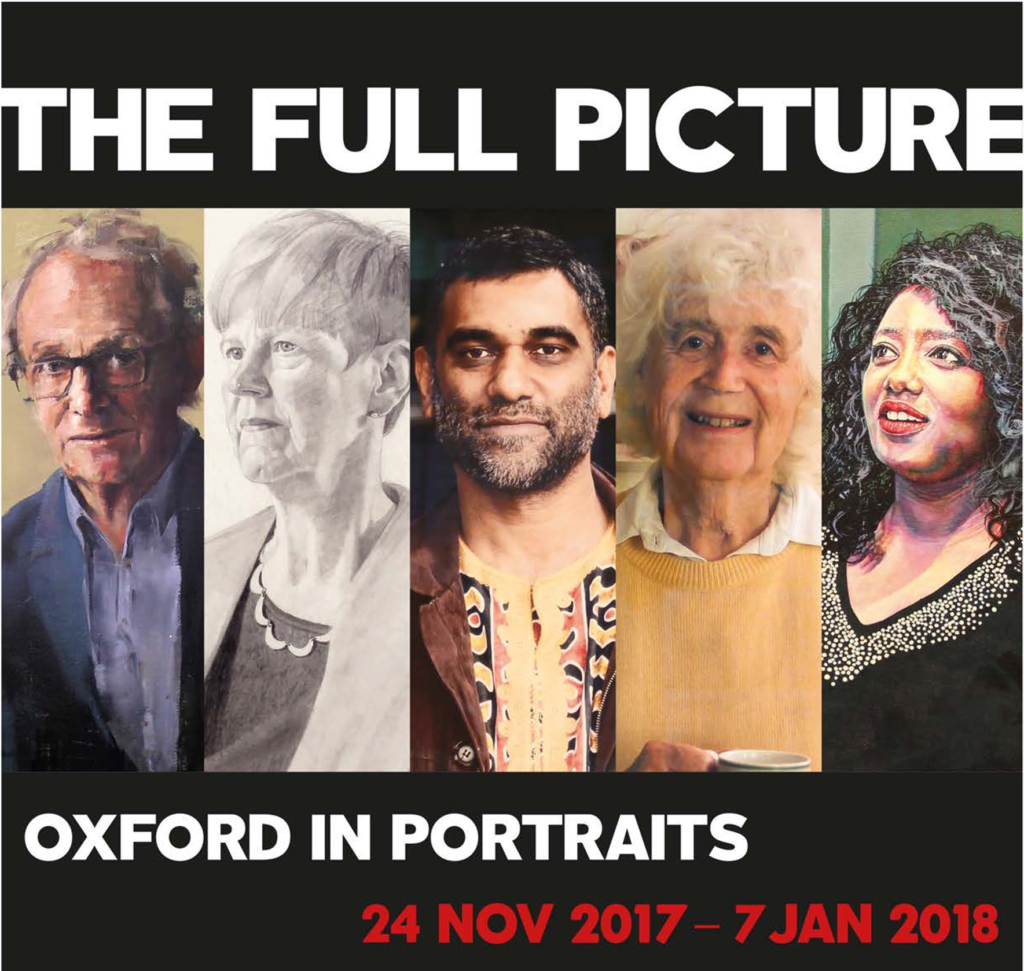

Many universities tailor their existing collection development plans—or create new ones—in an attempt to focus and/or diversify their collections. Edinburgh’s University Art Collection, for example, is currently prioritizing its Contemporary Art Research Collection. The University of Oxford, in a recent attempt to diversify their portrait collection, created the Diversifying Portraiture project that first catalogued existing university portraits of historical figures who “challenged the stereotypes of their time,” and then commissioned 24 new portraits of more recent university individuals from diverse backgrounds and communities.[2] The resulting exhibition, The Full Picture, aimed to show how “Oxford is, and always has been, a more diverse place than most would recognise.”

There is an inherent risk to attempting to fill “diversity gaps” in institutional collections. There are clear resonances between institutional attempts to retroactively diversify their collections, and the feminist art historical project to “uncover” the women excluded from art history. As Griselda Pollock critiques in Differencing the Canon, this revisionist project in fact “fundamentally unaffected” the history of art, as “despite the expanding volume of research and publications on artists who are women, Tradition remains the tradition with the women in their own special, separated compartments, or added as politically correct supplements.”[3] Instead, Pollock suggests that more effective change comes from “differencing the canon”: engaging in “productive and transgressive ways to re-read the canon and…the disciplinary formation that establishes and polices [it].”[4]

Indeed, some universities’ approaches to their art collections resonate with Pollock’s art historical call for “re-reading” institutional structures. Instead of revising collections development policies or seeking to acquire new, supplementary material, these university art collections instead actively revisit the material they already hold. This can take a number of different forms, including academic research projects, new curatorial methods, and artist-led interventions.

In 2001, artist Mark Dion collaborated with students and staff at the University of Minnesota’s Weisman Art Museum on a research and curatorial project that aimed “to consider more fully how one university has collected and used objects to produce knowledge within disciplinary structures.”[5] In a catalogue essay for Cabinet of Curiosities: Mark Dion and the University as Installation, E. Bruce Robertson observes that university collections produce knowledge notably differently from the rest of the university institution, which valorizes textually-based knowledge production. He writes

Object collections… are dispersed and virtually invisible to outsiders: the official museum collections are the tip of the iceberg of the specimens and artifacts owned by the university. Moreover, physical collections have begun to be discounted as sites of knowledge production, unlike the laboratory for the sciences, fieldwork for the social sciences, the library and archive for the humanities. Instead they tend to be conceived of as repositories—or at least that is what many academics would believe.[6]

In light of this observation, research projects led by artists—rather than academics—could therefore be understood as a compelling method for university art collections to “re-read” themselves and their histories outside of the broader institutional framework, while also allowing for new modes of public engagement.

Dion notes, however, that such projects are “fundamentally site-specific.”[7] This raises a particular challenge for university art collections seeking relevance to a broader public; a challenge closely tied to broader institutional goals of forming relationships with external communities alongside the diversification of their own internal research, teaching, and collections.

In “Art in Special Collections: Latino and African American Fine Art and Photography Collections in Academic Institutions,” Rebecca Hankins and Miguel Juárez suggest that the two projects of community outreach and internal diversification are entwined. They discuss how university collections may not have the diversity “gaps” they think they do—some of the material may already be there, just obscured and under-researched. Hankins and Juárez call for institutions to address this issue by making their collection material “visible” to the public via digitization.[8] They identify digitization as one of the most important actions institutions can take, writing that “the physical door is not the only portal for viewing an institution’s holdings. Providing collections via digital projects is a virtual door that goes hand in hand with providing multiple levels of access.”[9]

University art collections’ approaches to acquisitions and engagement are to an extent informed by broader institutional calls for diversity and accessibility. It is important to note, however, that in many regards these are questions they have always engaged. Indeed, the oft-critiqued “haphazard” collecting strategies underpinning many of these university collections seems tied to a unique inherent flexibility and creativity. The Weisman Art Museum was founded in 1934; its first director, Hudson Walker, remarked that the university collection “should emphasize a ‘workshop character,’ as opposed to the ‘traditional notion of a museum as a place for safekeeping of rare objects.’”[10] This encouragement for creative community engagement is also apparent in a 1944 description of the University of Nebraska Art Collection, which describes:

pictures are loaned continually…. A “picture of the month” program is kept going in the University of Nebraska Student Union the year round. Extension Art Exhibitions that include work from the University’s collection are often sent to county fairs and exhibited alongside fancy work, canning exhibits, and even hog shows. The most sincere appreciation and criticism of paintings often comes from Nebraskans of rural districts—farmers are avid art enthusiasts.[11]

There is a sustained focus throughout these historical and contemporary university collection documents on making art accessible and enriching to the lives of all on campus and in the broader community. The challenge of making university collections publicly relevant has been longstanding; and “re-reading” their “unorganized” histories is just as important as new acquisitions to keep them continually engaging.

[Word Count: 1,066]

Footnotes

[1] Matthew Reisz, “What is the point of university art collections?” Times Higher Education (July 29, 2015), https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/what-is-the-point-of-university-art-collections.

[2] The University of Oxford, The Full Picture: Oxford in Portraits (Oxford: University of Oxford, 2017), exhibition booklet, https://edu.admin.ox.ac.uk/files/thefullpictureexhibitionbookletpdf.

[3] Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (London: Routledge, 1999), 23.

[4] Pollock, 34.

[5] Colleen J. Sheehy, “Introduction: Restaging the Cabinet of Curiosities,” in Cabinet of Curiosities: Mark Dion and the University as Installation, ed. Colleen J. Sheehy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xiii, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv73x.5.

[6] E. Bruce Robertson, “Curiosity Cabinets, Museums, and Universities,” in Cabinet of Curiosities: Mark Dion and the University as Installation, ed. Colleen J. Sheehy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 44, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv73x.8.

[7] Bill Horrigan, “A Conversation with Mark Dion,” in Cabinet of Curiosities: Mark Dion and the University as Installation, ed. Colleen J. Sheehy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 40, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv73x.7.

[8] Rebecca Hankins and Miguel Juárez, “Art in Special Collections: Latino and African American Fine Art and Photography Collections in Academic Institutions,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 29, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 34, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27949536.

[9] Hankins and Juárez, 34.

[10] Rebecca Wilson, “Hudson Walker: Curator, Patron, Friend,” Weisman Art Museum, July 18, 2012, https://wam.umn.edu/2012/07/18/hudson-walker-curator-patron-friend/.

[11] Dwight Kirsch, “The University of Nebraska Art Collection,” College Art Journal 3, no. 4 (May 1944): 155, https://www.jstor.org/stable/773205.

Bibliography

Hankins, Rebecca, and Miguel Juárez. “Art in Special Collections: Latino and African American Fine Art and Photography Collections in Academic Institutions.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 29, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 31–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27949536.

Horrigan, Bill. “A Conversation with Mark Dion.” In Cabinet of Curiosities: Mark Dion and the University as Installation, edited by Colleen J. Sheehy, 29–42. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv73x.7.

Kirsch, Dwight. “The University of Nebraska Art Collection.” College Art Journal 3, no. 4 (May 1944): 152–156. https://www.jstor.org/stable/773205.

Pollock, Griselda. Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories. London: Routledge, 1999.

Reisz, Matthew. “What is the point of university art collections?” Times Higher Education (July 29, 2015). https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/what-is-the-point-of-university-art-collections.

Robertson, E. Bruce. “Curiosity Cabinets, Museums, and Universities. In Cabinet of Curiosities: Mark Dion and the University as Installation, edited by Colleen J. Sheehy, 43–54. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv73x.8.

Sheehy, Colleen J. “Introduction: Restaging the Cabinet of Curiosities.” In Cabinet of Curiosities: Mark Dion and the University as Installation, edited by Colleen J. Sheehy, xi–xiv. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv73x.5.

The University of Oxford. The Full Picture: Oxford in Portraits. Oxford: University of Oxford, 2017. Exhibition booklet. https://edu.admin.ox.ac.uk/files/thefullpictureexhibitionbookletpdf.

Wilson, Rebecca. “Hudson Walker: Curator, Patron, Friend.” Weisman Art Museum. July 18, 2012. https://wam.umn.edu/2012/07/18/hudson-walker-curator-patron-friend/.