We know that hundreds of deaf children were late diagnosed in the NHS Lothian area, many severely late so they experienced language deprivation. Here we look at the statistics collected using the CRIDE Survey. This is an annual survey completed by the heads of local authority services for deaf children and returned to CRIDE, the Consortium of Research in Deaf Education. CRIDE is a group of bodies interested in deaf education, including the National Deaf Children’s Society (NDCS), the British Association of Teachers of Deaf Children and Young People (BATOD) and various academics. I am one of them. We have a Scotland CRIDE group which has increased the participation in this survey from Scotland over the past few years.

Using CRIDE results, we will explore the number of deaf children and the number of teachers of deaf children (ToDs) in the five local authorities affected by the NHS Lothian Audiology scandal: West Lothian, Edinburgh, East Lothian, Midlothian and the Scottish Borders.

I compared CRIDE results from the other authorities in Scotland over the same period. I checked the average number of children on the case load and teachers of deaf children per local authority but took out the five local authorities affected by the audiology errors. This was to see if there was any difference between the Lothian results and the rest of Scotland.

Over the same period, the NDCS has been running a campaign to try to increase the number of teachers of deaf children to the levels that existed a decade ago. Restrictions on local authority finances over this decade have often led to ToD posts being cut.

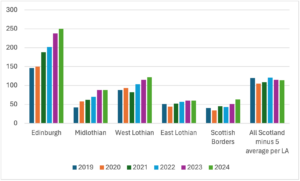

Figure 1. Change in number of deaf children on the caseload per authority 2019 – 2024.

In the first chart (Fig. 1) we can see a rapid rise in the number of deaf children in Edinburgh from 2021. The other four authorities all have rises too, but they also have much smaller populations. The right-hand group of clustered bars shows the average number of deaf children on the caseload per local authority in the rest of Scotland, taking out the five affected authorities. You will notice that Edinburgh, as a large authority, has many more deaf children on its caseload than the average across Scotland. We don’t see any rise in average caseload numbers in the rest of Scotland over this period 2019-2024.

We need to go back to the chronology of when the parents of Child A made a complaint (November 2018) which was rejected by NHS Lothian (February 2019). The parents then made a complaint to the Ombudsman (July 2019). This complaint was upheld (May 2021). The British Academy of Audiology started work and their report was published (December 2021).

CRIDE data are collected in January of each year. The story about the NHS Lothian Audiology failings broke in December 2021, just weeks before the 2022 CRIDE survey went out. So initially we might expect an increase in referrals from audiology to show up the year afterwards in the 2023 data. But in fact, we can see this increase of referrals must have started during 2020 because they show up in the data collected for CRIDE in January 2021, particularly in Edinburgh.

It is likely that NHS Paediatric Audiology began to inspect their own processes from the time of the referral to the Ombudsman, and many children were referred while the BAA audit was going on, before the official announcement about child A in May 2021 and the result of the BAA report in December 2021.

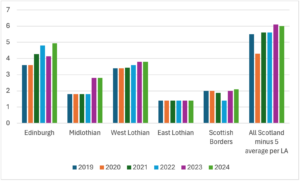

Figure 2: Change in the number of teachers of deaf children per authority 2019-2024.

Now looking at the number of teachers of deaf children per local authority (Fig.2) we can see how the different councils responded to the increase in referrals. Looking at the all-Scotland figures first, on the far right of the chart, that is the average of all the other local authorities which were not affected by the NHS Lothian audiology failings, we can see a small rise in the number of teachers of deaf children per local authority. This may be due to the success of the NDCS campaign.

At the same time, in the five affected authorities, we see different staffing patterns. The Scottish Borders and East Lothian have not responded to the increasing number of children referred from health after the revelations at the end of 2021. But Edinburgh, Midlothian and West Lothian have been able to increase the number of teachers of deaf children, which seems to be in response to the increasing numbers of children they now know about.

Congratulations are due to Midlothian Council for opening a resource base for deaf pupils in a newbuild primary school, Easthouses. It should open this August 2024. This will at last provide more choices for families affected by the late diagnosis scandal and could well be popular with parents from nearby authorities too. The team of teachers of deaf children has consistently supported the families in the FLAAG parents’ group. They refer parents to the group and regularly attend the Deaf Children’s club organised by parents in Midlothian.

In Edinburgh the Council has recently employed a tutor of BSL to provide tuition in BSL to deaf children, again a positive development for late diagnosed deaf children who urgently need a language. For the late diagnosed deaf children, BSL is an important and easy way into a language to prepare children for school and learning. West Lothian, on the other hand, according to CRIDE returns does not employ any BSL tutors, Communication Support Workers or interpreters to support deaf children, despite there being some extremely late diagnosed deaf children in this authority.

We can only hope that NHS Lothian has now referred all the late diagnosed children after retesting. Reports from ToDs suggest that the NHS is still not informing councils about whether a newly referred deaf child was part of the audit, i.e. retested and referred late. The NHS has a statutory duty of candour to patients, deaf children and their parents which it has fulfilled, at least for the most affected children. It also has a wider moral duty of candour to other services such as local authorities. Councils need to make provision for late diagnosed deaf children, and this is often different provision to what they have provided up till now. It has been difficult for councils at a time of extreme financial constraints to increase staffing.

There may be other deaf children, possibly older and never diagnosed, who later turn up in institutions or prisons appearing to have learning difficulties and autism. How can we be sure? As the difficulties with testing in the Lothian paediatric audiology department were poor since at least 2009, how do we know that there are not young people who have now left school who have never been diagnosed as deaf? We need ongoing candour from NHS Lothian and close liaison with council services for young people who have challenging behaviour – many could be deaf without anyone knowing.

So, to sum up, there are significant increases in numbers of deaf children known about in most of the five Lothian authorities over the 2019-2024 period, not seen in the rest of Scotland. The councils have responded in different ways in terms of staffing and planning. More openness from NHS Lothian is needed to reassure families, services for deaf children and elected councils that all the late diagnosed deaf children and young people have now been referred with full disclosure about their diagnosis history.

Thanks to CRIDE for support with their data.