“It is often assumed that the Abbasid fiscal system was centralized and that a large portion of regional revenues were sent to the capital.” This hypothesis is explored in our project, where I (Noëmie Lucas) trace how provincial revenue was moved, as evidenced in the literary corpus. In this blog post, I provide an example from the corpus and elaborate on the type of information we can gather.

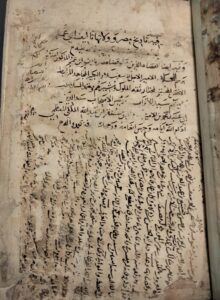

Folio from the manuscript of the Kitāb al-Wulāt, unicum held at the British Library

As our PI, Marie Legendre, states in the project description regarding the centralization of revenues, “This is the point at which narrative texts must be considered, as papyri do not document the upper echelon of the administrative hierarchies.” One such narrative text, and one of the earliest written by an Egyptian, is al-Kindī’s Kitāb al-Wulāt. Abū ʿUmar Muḥammad b. Yūsuf al-Kindī al-Tujībī (283-350/897-961) was a tenth-century Egyptian historian during the Ikhshidid rule. His Kitāb al-Wulāt is often seen as “a summary of Egyptian administrative history” (Bouderbala, 48). In this post, I focus on an instance of revenue transfer from Egypt during the reign of Hārūn al-Rashīd (786-809), as recorded in Kitāb al-Wulāt.

The main character in this anecdote is Al-Layth b. Faḍl, a man from Khurāsān who governed Egypt for Hārūn al-Rashīd between 182/798 and 187/803. Afterward, he became governor of Sistān (814-815) during al-Maʾmūn’s caliphate.

The narrative states:

“Then, he left for al-Rashīd on the seventh day of Ramaḍan, year 183, with the revenues and gifts while still governor, appointing his brother ʿAlī b. Faḍl as his deputy over Egypt. Al-Layth returned to Egypt at the end of year 183 and left again with the revenues seven days before the end of Ramaḍan, year 185, appointing Hāshim b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Muʿāwiya b. Hudayj as his deputy. He returned on Saturday, the fourteenth day of Muharram, year 186.Ibn Qudayd told me: Each time that al-Layth b. Faḍl closed the fiscal year and completed the accounts, he left with the revenues and accounts to the Commander of the Faithful, Hārūn.”

This anecdote is particularly rich because it provides specific details about

Timing of Departure

Al-Layth left Egypt with the revenues after the closure of the fiscal year (ighlāq al-kharāj), a concept that echoes the opening of the fiscal year (iftitāḥ al-kharāj). On both occasions, he departed during Ramaḍan (each time in October), indicating that all revenues had been collected by then. The fiscal calendar was not aligned with the Hijri lunar months but was seasonal, based on crop cycles. Studies, such as J. Cromwell’s on the early eighth century, suggest that the fiscal year ended in early autumn. Another example, from ʿUmar b. Mihrān’s tenure as fiscal administrator in 792, also shows that revenues were collected by late September.

Duration of Absence

The dates of al-Layth’s absences are well recorded, as are the names of his deputies while he was away:

- 12 October 799 – end of January 800

- 3 October 801 – 23 January 802

This indicates an absence of about three and a half months. Using the al-Thurayya project tools, I estimated that the journey from Egypt to Iraq took around five weeks, suggesting that al-Layth did not stay long after delivering the revenues before returning to Egypt. The destination of the revenues is worth discussing, as it impacts the duration of the journey.

Destination of the Revenues

The text does not specify where al-Layth delivered the revenues, only that they reached the caliph. From 180/796-797, Hārūn al-Rashīd had settled in Raqqa. During his pilgrimage in 186/802, he left ʿUthmān b. Nahīk al-ʿAkkī in charge of the Treasury in Raqqa, indicating that the city housed the main governmental institutions. It is therefore likely that al-Layth delivered the revenues to Raqqa rather than Baghdad. According to al-Thurayya’s project, the journey from Fusṭāṭ to Raqqa took about 27 days, slightly shorter than to Iraq.

The Fiscal Convoy

The account offers clues about what was transported. It mentions that “each time that al-Layth closed the kharāj of a year (closed the collection year) and completed the accounts, he left with the revenues and the accounts”. In other words, after collecting the taxes, the second step was to verify that the correct amount had been collected. It is noteworthy that the governor not only brought the revenues himself but also carried the accounts, for verification purposes at the imperial level too.

These accounts concerned the revenues, this « māl » that Layth is said to have moved. These revenues included a substantial amount of coins but it appears that fiscal revenues were often accompanied by other artifacts, sometimes referred to as gifts (hadāya). al-Layth b. Faḍl is said to have brought “al-māl wa-l hadāya” (money and gifts) which means that not only coins were transported but other gifts, among those embroidered textiles (ṭirāz).

Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l’Islam, OA 6649 – © 2007 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Claire Tabbagh

From this example, it could be argued that the transfer of tax revenues from a province to the central treasury, regardless of its frequency, destination, or the nature of the convoy, was part of the regular fiscal administration. However, these routine activities are rarely the focus of universal histories, annalistic accounts, or even administrative histories like al-Kindī’s Kitāb al-Wulāt. Based on my exploration of the corpus so far, such activities are typically only recorded when an irregularity occurs.

In al-Layth b. Faḍl’s case, the irregularity may stem from his portrayal as an exceptionally efficient administrator, whose successful transfer of revenues was noted as evidence of his proficiency. The perception of his actions as exceptional is worth further investigation, which I continue to explore in my research.

Banner image: Detail from the Catalan Atlas

This post has been written by Noëmie Lucas.

Leave a Reply