In this post, postdocs Noëmie Lucas and Eline Scheerlinck join forces and explore the relationship between travel and taxation in Abbasid fiscal documents, focusing on 3 tax receipts that may or may not have functioned similarly to travel permits, akin to modern-day passports, for taxpayers in 8th and 9th-century Egypt.

This post is co-written by Noëmie Lucas and Eline Scheerlinck.

To understand this, we first need to step back in time. There is considerable evidence from the Umayyad period—found in Arabic, Greek, and Coptic papyri—that sheds light on the new Arab-Muslim government’s efforts to monitor taxes, taxpayers, and their movements. Even in the immediate aftermath of the conquest, letters from high-ranking officials to local administrators reveal concerns about potential population flight due to taxation, with orders to prevent people from travelling.

A significant administrative archive from the 660s, belonging to the pagarch Flavius Papas of Edfu in southern Egypt, contains documents addressing measures taken by the government to deal with fugitives. By the first half of the 8th century, the government’s interest in controlling movement became even more prominent. The dossier of Basileios, the local administrator of Aphrodito, includes both Greek and Arabic letters from the Arab-Muslim governor, Qurra b. Sharīk, which regularly outline actions to track, apprehend, and punish fugitives.

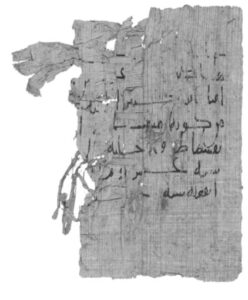

Umayyad Travel Permits

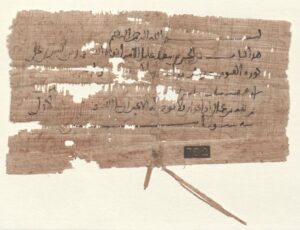

Umayyad Travel Permit in Arabic. P.Pierpont Morgan inv. Ms M. 662 B.35e

Saqqara(?), February -March 729. Naïm Vanthieghem, BASP 53 (2016) 233-238.

Moreover, between 717 and 751, Arabic travel permits and similar Greek documents were issued, allowing individuals to travel for a specified period to earn a living and pay the capitation tax. A Greek travel permit explicitly links these permits to fugitives, stating that the document served as proof of the carrier’s freedom and prevented them from being mistaken for a xenos, a term used in Greek papyri to refer to someone outside their registered district. Government policies are clearly reflected in the 15 published Arabic travel permits, which often mention that the bearer was travelling to work and pay their taxes. Additionally, evidence suggests that providing a guarantee for tax payment was a prerequisite for obtaining a travel permit. These permits were highly detailed, often including physical descriptions of the traveller, much like the photographs in today’s passports.

Interestingly, all of these travel permits date between 717 and 751. After this period, references to fugitives, travel, and their connection to taxation largely disappear from the papyrological record. This raises an intriguing question: Did people no longer need travel permits in the Abbasid period?

Travel by Tax Receipt in the Abbasid Period?

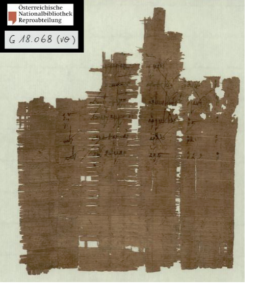

The surviving Arabic and Greek papyri from the early Abbasid era show that the government continued to control people’s movements. For example, Greek fiscal registers from the second half of the 8th century contain marginal notes indicating that some taxpayers had either fled or died (CPR XXII 33, 34). Additionally, a list of arrested fugitives shows that the government was still actively tracking and detaining individuals who had fled to other regions (CPR XXII 35).

Greek list of abandoned lands, with reasons for abandonment. Second half 8th century, Fayyum. CPR XXII 33. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

Some scholars have proposed that by the Abbasid period, carrying a tax receipt may have been sufficient for travel. This hypothesis is based on three published Arabic tax receipts from the Abbasid period, as well as three unpublished ones (Vanthieghem-Pilette, 2016). Ragib (1997) also notes a passage from the History of the Patriarchs, in which the Caliph Hishām (r. 724–743) is praised for issuing tax receipts to all Egyptian subjects to protect taxpayers from unfair treatment. However, how closely this policy was related to travel remains uncertain.

The primary link between the Umayyad travel permits and the three Abbasid tax receipts is the inclusion of a protective formula, not commonly found in other documents until the Fatimid period: “Whomever of the agents of the amir meets him, should show him nothing but good.” In the Umayyad travel permits, this formula protected the bearer from being arrested, suggesting that the agents of the amir—subordinates of the issuing authority—were not to interfere with the traveller. Scholars like Ragib (1997) and Vanthieghem & Pilette (2016) have suggested that these Abbasid tax receipts may have served a similar function to the earlier travel permits.

The three published tax receipts, written on papyrus, are not entirely uniform, though they belong to the same document type. They date from the late 8th to early 9th centuries (784, 812, 821). Two of the receipts are related to the Fayyum, either because the taxpayer resided there or because the tax administrator oversaw the region’s taxes.

Two of the receipts specifically mention the payment of the capitation tax, one for 10 dinars and another for 1/2 dinar (P.DiemFrueheUrkunden 7 and P.GrohmannProbleme 18). However, these amounts are unusual—either too high or too low—since the capitation tax during this period typically ranged between 1 and 4 dinars. In the third receipt (CPR XVI 1), a payment of over 200 dinars is recorded, though the type of tax is unclear. Given the size of this sum, Werner Diem, the editor of the document, suggests it may have been a land tax, though this interpretation remains debatable, as we will point out below.

The documents follow the general formulaic structure of other Arabic tax receipts from this period, including the issuing authority, the taxpayer’s name, the sum of money, the type of tax, and the tax year. The protective phrase is added just before the date, similar to the earlier travel permits. However, the documents also contain interesting features beyond the protective formula.

The Three Documents

Let’s examine the three published receipts in more detail:

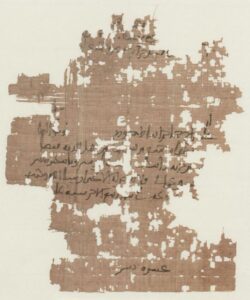

1. P.DiemFrueheUrkunden 7 (784, Egypt)

This document states that it is issued by the governor of Egypt, Mūsa b. Muṣ’ab, who is described as amīl amīr al-Mu’minīn—essentially a subordinate of the caliph. Mūsa is noted as the authority over the taxes of Egypt and all its districts. After this heading, the scribe left a considerable blank space. The document then mentions “…over the kharāj of the people at the head (literally, ‘skulls’ or heads) of the peasants of the kura (district) [blank space in the document] and its surroundings (jawālīha) and its peasants and all those living among the ahl al-dhimma.” Interestingly, the scribe seems to have left a space for the name of the district, which suggests that this document may not have been unique. More with the same formula might have been produced for other districts.

P.DiemFrueheUrkunden 7. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

The editor of this document translated jawālīha as “capitation tax,” and it has been cited as the earliest attestation of this term with that meaning, rather than jizya. However, after careful reading, we concluded that while jawālīha would later come to mean “capitation tax,” the term here better translates as “surroundings.”

Though fragmentary, the document acknowledges a payment of 10 dinars for the capitation tax for the year 168. The protective phrase follows, and the date appears at the bottom. Also, at the bottom of the papyrus is a note indicating the amount paid—10 dinars. As mentioned earlier, the sum of 10 dinars seems unusually high for a single person’s poll tax for one year. Fiscal papyri from the time show that certain individuals would pay or stand guarantor for the taxes of multiple people. This may be what occurred here, though the document does not explicitly state this.

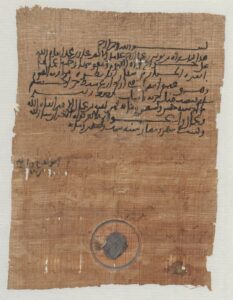

2. P.GrohmannProbleme 18 (812, Fayyum)

This document was sealed and is the only document that explicitly refers to itself as a receipt, stating: “hādhā kitābu barāʾat” (“this is a receipt”). The issuing party, Yūnus b. ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān, describes himself as the agent of the amir ʿAbbād b. Muḥammad. From the document, we infer that Yūnus was a fiscal administrator responsible for taxes in the kura of Fayyūm and its subdistricts, rather than the financial director of the entire province, as editor Grohmann initially suggested.

P.GrohmannProbleme 18. Austrian National Library, Vienna

This receipt has the most in common with the earlier travel permits, as it includes a description of the taxpayer, detailing their profession, domicile, and physical characteristics: he is stocky, light-skinned, eagle-nosed, with narrow curved eyebrows, bald at the temples, straight-haired, and corpulent. This detailed physical description closely parallels those found in the Umayyad travel permits, which also included identifying details of the traveller.

3. CPR XVI 1 (821, Fayyum)

This short receipt, which was sealed, was issued by Ḥasan b. Saʿīd, the subordinate of the amir Muḥammad b. as-Sarī. Similar to the issuing party in P.GrohmannProbleme 18, Ḥasan was a local administrator in the Fayyūm region. However, his position is phrased differently. Unlike Yūnus, who is described explicitly as being in charge of taxation, Ḥasan is simply noted as being ʿala kura al-Fayyūm without any specific reference to tax responsibilities.

CPR XVI 1. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

This document is particularly notable for mentioning an unusually large sum of over 200 dinars, though both the exact amount and the taxpayer’s name are lost due to damage. We do have some doubts about the reading of this high number, i.e. miʾatayni (“for 200”). It is unusual for the type of tax not to be mentioned before the amount, and large portions of the papyrus are missing, which makes definitive conclusions difficult. Additionally, significant sections of the preceding line are also damaged, further complicating the interpretation. If we accept the reading of “200” and that this represents a tax payment, it would be an enormous amount—likely representing taxes for an entire district or multiple taxpayers.

None of these documents explicitly mention travel by the recipient. While the protective phrase could be interpreted as a form of travel allowance, we do not find this evidence conclusive, especially given the variation among the three documents. The protective phrase, while clearly reminiscent of the Umayyad travel permits, may have had a different function in these specific Abbasid documents. The physical description in P.GrohmannProbleme 18 bears some resemblance to the earlier travel permits, but this alone is not enough to support the notion that these receipts served a similar function. More evidence, particularly from unpublished receipts, is needed to fully understand their purpose, and we look forward to discussing them with our colleagues in the field.

Coptic and Greek documents in this post are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”. Arabic documents are cited according to “The Checklist of Arabic Documents”.

This post has been written by Eline Scheerlinck and Noëmie Lucas.

Leave a Reply