On our blog, we have explored various sources for studying Abbasid fiscal practices, including literature, inscriptions, coins, and papyrus documents from the fiscal administration. In this post, I aim to highlight a perhaps less obvious source of information on the fiscal system: private letters on papyrus. Unlike other papyrus documents—such as lists, registers, tax demands, tax receipts, writing exercises, or correspondence between administrators—private letters were not direct products of the fiscal administration. So, what traces did the fiscal apparatus leave in documents from the private sphere?

It is worth noting that distinguishing between the private and public spheres in these documents can be quite challenging. Determining whether a document is “official” or “unofficial” is often complex. In many cases, attempts to differentiate between the two are unproductive, as both individuals and the documents they produced often straddled the line between public and private roles.

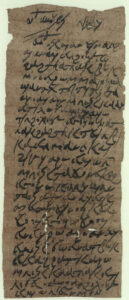

CPR XXXIV 64 recto. Austrian National Library, Vienna. K 3223.

The first letter I wish to discuss is CPR XXXIV 64, which is currently housed in the Austrian National Library in Vienna and which has been tentatively dated to the ninth century. The address is positioned at the top: Abou al-Eid is writing to Piheu. The phrase “with God”, which opens both the address and the letter itself, is found in multilingual letters from Egypt in the ninth and tenth centuries. A clear hierarchical distinction exists between the writer and the recipient, as the former issues several commands and appears to reprimand the latter. The central issue in the letter concerns a man named Aspak. It seems Piheu gave Aspak a gold coin (holokottinos) which should have been withheld for tax payment. The letter mentions a “tax levy” (ⲉⲧⲓⲗⲟⲅⲏ, Greek: λογή), and the writer instructs Piheu to recover the gold coin from Aspak and provide him with an equivalent amount of wheat instead.

Interestingly, the writer advises Piheu to take “the men of Maiouma” with him to retrieve the coin. Maiouma was a village in Middle Egypt, in the district of Hermopolis. These “men” were likely local authorities, possibly involved in tax collection. Their presence was probably intended to exert pressure on Aspak to surrender the coin.

CPR XXXIV 64 verso. Austrian National Library in Vienna. K 3223.

Neither the writer nor the addressee is given a title or profession indicating a role within the administration. However, this is typical of Coptic letters from this period and does not necessarily imply that this is a private letter. What suggests that this letter was written in a private context, rather than as part of the fiscal administration, is the writer’s numerous commands related to agricultural work, and even the indication that he would come personally to sow or plant wheat fields.

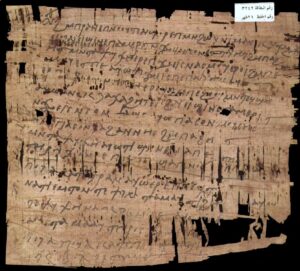

P.Christ.Musl. 25 recto. Berkes, Lajos, ed., Christians and Muslims in Early Islamic Egypt. Ann Arbor, MI: American Society of Papyrologists, 2022, p. 165. Fig. 30.

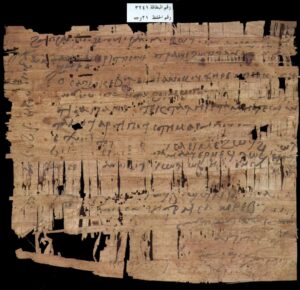

The second letter I wish to highlight briefly is P.Christ.Musl. 25, a papyrus containing a draft letter from one woman to another. Zachaheu is writing to Trashe, and it also contains writing exercises. It forms part of the Coptic collection at the National Library and Archives of Egypt (Dār al-Kutub) and has been tentatively dated to the ninth or tenth century. One side of the papyrus consists almost entirely of greetings and blessings, while the other side contains fragmentary remains of a request for assistance. The writer’s difficulties appear to be financial, as she references payment of the dapanē tax. Unfortunately, due to the fragmentary condition of the text, the exact meaning remains unclear.

P.Christ.Musl. 25 verso. Berkes, Lajos, ed., Christians and Muslims in Early Islamic Egypt. Ann Arbor, MI: American Society of Papyrologists, 2022, p. 166. Fig. 31.

In conclusion, while private letters may not be direct products of the fiscal administration, they offer valuable glimpses into the fiscal realities of the Abbasid period, blurring the lines between public and private spheres. These documents highlight how taxation and administrative practices permeated everyday life, even within personal correspondence.

Coptic and Greek documents in this post are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”.

Banner image credit: Marie Legendre.

This post has been written by Eline Scheerlinck.

Leave a Reply