On our blog, we are exploring various types of papyrus documents that allow us to study the Abbasid fiscal system, as they form the core of the Caliphal Finances project’s sources. E.g., in this blog post, I, postdoc Eline Scheerlinck, focus on tax receipts, tax demand notes, and fiscal records. Those documents constitute the working papers and communications with taxpayers produced by the fiscal administration at various levels. Here, I highlight Greek scribal exercises found among the fiscal documents, which provide evidence of scribes practising phrases and numerals for use in fiscal administrative documents.

In this post, I will examine an example of another type of papyrus document that reveals information about the functioning of the fiscal system: administrative letters.

The papyrological record includes correspondence between administrators of various levels discussing fiscal matters. These letters can be top-down, where an official addresses their subordinate, or, less commonly, bottom-up, where a lower official addresses their superior. The Egyptian papyri offer a wealth of administrative correspondence from the 7th and early 8th centuries, as the dossiers and archives of several local officials have been discovered in Egypt and subsequently edited. Administrative correspondence from the Abbasid period is less prevalent and more dispersed, but there are still interesting examples that shed light on the fiscal system and its operation.

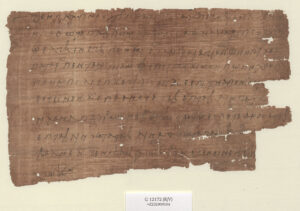

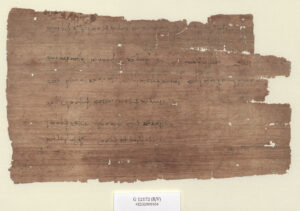

The letter in the image below, published as P.Christ.Musl. 16, was written in Coptic in 758 or 759 in the Fayyum, and is now housed at the Austrian National Library in Vienna. It was sent by the village authority Beliamin, son of Pecōsh, and the scribe Makari, both from a village named Hōki. They addressed Yaḥyā b. Hilāl, who was then the district administrator of the Fayyum. In the letter he is called both pagarch and amir, offices and titles that we will discuss in a future blog post. After the letter was sent, it was reused, likely at the office of the district administrator where it was received, for Greek scribal practice, repeating common personal names and names of villages in the Fayyum (published as Stud.Pal. X 172).

P.Christ.Musl. 16, letter from village authorities to the district administrator, about the taxes of the year 140/758.

This is my translation of the Coptic letter:

“+ In the name of God, firstly. It is I, Beliamin, son of Pecōsh, the lefpōshn (village authority) of Hōki and Makari, the scribe of…, we write to our lord, the amir Yaḥyā, son of Hilāl, the pagarch of our district, Fayyum, agent of Mūsā, son of Kaʿb, the governor of the land of Egypt. Our lord sent us an order, that what we sent to the treasury is in… of Chaēl the zygostatēs and his colleagues. And here is what we have sent to the treasury, per instalment and per day…to you for the taxes (in cash) of the 12th indiction year, year 140, namely, these. + Written…of the village Hōki.”

So, what did the village authorities wish to communicate to the district administrator? The letter concerns the taxes for the year 140 Hijri. Beliamin and Makari were responding to a letter containing an order or request from the district administrator. Although they indirectly cite or paraphrase the district administrator’s letter, it is not entirely clear what he actually instructed them to do. It seems that he wanted to know the exact amounts of taxes that Beliamin and Makari had collected in their village and sent to the local tax office of a certain Chaēl, who held the fiscal office of zygostatēs, an official involved in tax collection and tax burden distribution, and who will also be discussed in a future blog post. Beliamin and Makari responded to this order by ostensibly detailing the amounts of taxes they had collected for each instalment, on each day, thus providing a thorough account. The letter concludes without any greetings, simply ending with the date and mention of the village Hōki. On the verso, the side of the papyrus later reused for scribal exercises, a registration note was written in Greek indicating that the letter came from the village of Hōki and was written in Coptic (“From the village Hōki, Egyptian”). Someone in the office of the district administrator Yaḥyā ensured that the letter was correctly archived, and it appears that noting the language of the correspondence was also important in this archival practice.

Stud.Pal. X 172, Greek scribal exercises on the back of P.Christ.Musl. 16. Towards the bottom, a Greek archival note for the Coptic letter on the other side.

Interestingly, the detailed list of taxes, “per instalment and per day,” is not provided on this piece of papyrus, although the letter seems complete. The writers refer to the list of taxes with the phrase “namely, these” (ete nei ne), as if the list should follow next. However, what follows is a cross and the date, marking the end of the letter. The actual detailed list of taxes is not included. It is likely that the detailed list was sent on a separate sheet of papyrus, as suggested by the editors. However, examining the other side of the papyrus, it appears that the papyrus might have been cut, suggesting that this piece of papyrus was originally longer, and the list of taxes from the village of Hōkis may have been provided beneath the letter, which would better align with the wording of the text.

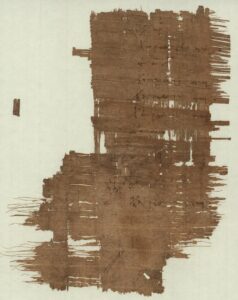

An example of a list, compiled about 30 years after our letter was written, and very close to what Beliamin and Makari professed to send the district administrator, is in fact known to us. Although the text is fragmentary, it seems to record tax payments within a specific instalment, recorded day by day over the span of five days. This document, published as CPR XXII 23, is also part of the papyrus collection of the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

CPR XXII 23, fiscal records listing specific successive days in the context of a tax instalment.

As we continue to analyse these documents, they offer invaluable insights in the administrative challenges and the meticulous record-keeping practices that shaped the multilingual Abbasid fiscal system. Letters between fiscal administrators tell us about their various roles and hierarchies, but also about the ways working documents and informative messages were transferred and archived.

Coptic and Greek documents in this post are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”.

Banner photo credit: Marie Legendre.

This post has been written by Eline Scheerlinck.

Leave a Reply