On Thursday 13th November, I, Postdoc Research Fellow Eline Scheerlinck, gave a lecture in the “Egyptian Christianities” series, organised by Zachary Chitwood (University of Munich) and Claudia Sode (University of Cologne). You can find a full programme of this fascinating series, which runs until February 2026, here as well as at the bottom of this post.

My lecture, “Protecting Tax Evaders, Securing the Revenue: The Paradox of Local Governance in the Early Islamic Egyptian Countryside,” delved into issues of taxation in the Egyptian villages of the 7th and 8th centuries. The protagonists of my talk were the rural elites, chief among them the village heads and other village authorities, their responsibilities in fiscal practice, and the documents which they produced. One particular genre of documents, the Coptic protection letters, presents a testimony of the complex relationships of power and dependency in the Egyptian countryside, with taxation playing an important role.

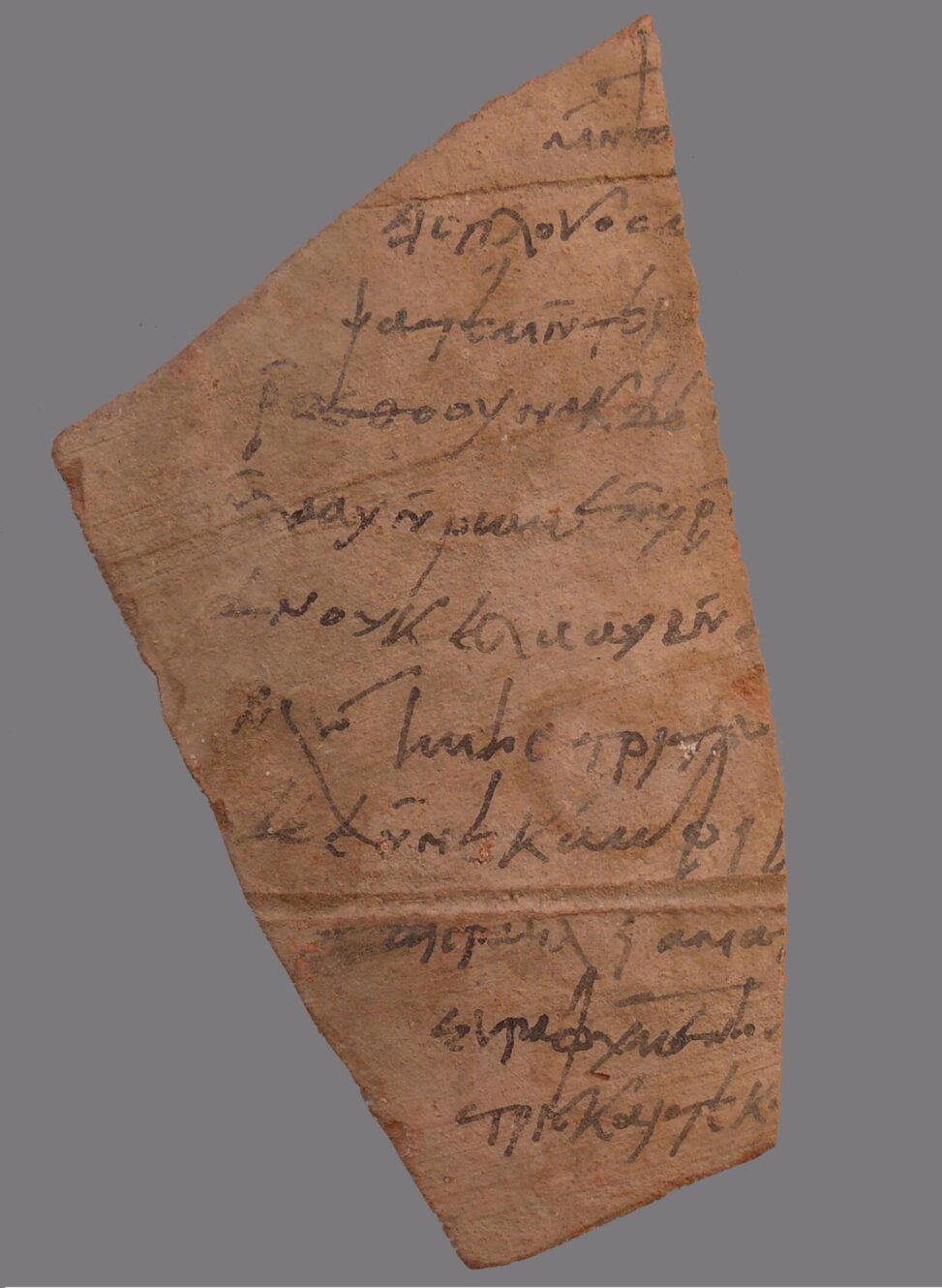

Examples of Coptic Protection Letters

In my lecture, I explored how the Coptic protection letters were instrumental in resolving issues of tax evasion in the villages. We focused specifically on the area of Western Thebes, including the village of Jeme and the monastic settlements in the area, since this is where the large majority of the Coptic protection letters come from. These letters, issued by local elites such as village heads and monastic leaders, provided amnesty to those who had fled due to unpaid taxes or unresolved disputes, allowing them to return without fear of prosecution. This mechanism was not a top-down mandate but a bottom-up development, which existed before the Arab-Muslim conquest but which intensified in the first half of the 8th century, that supported the provincial administration by ensuring a steady flow of revenue.

I argued that these letters were not merely private agreements but were deeply embedded in the social and fiscal fabric of village life. They reveal the intricate networks of power, where rural elites acted as intermediaries between the local communities and the central authorities. Through this mechanism, village elites could negotiate partial tax payments, thus securing immediate funds and ensuring long-term economic stability.

Remains of the monastery of Apa Paulos, Deir el-Bachit, Western Theban area, Egypt. Several Coptic protection letters were found at/were connected to this monastery. Photo by Roland Unger.

Moreover, these letters highlight the dual role of rural elites in both enforcing and mitigating fiscal policies. While appearing to act against the provincial directives by protecting tax evaders, the elites were actually supporting the empire’s goals by maintaining social and economic continuity in the villages. This pragmatic approach prevented the larger issue of displacement and reduced administrative burdens on the central government.

Ultimately, my research shines a light on the symbiotic relationship between local governance and the broader fiscal system in Early Islamic Egypt. By adapting central policies to suit local realities, the village elites not only reinforced their own positions of power but also contributed to the empire’s stability and success. This nuanced understanding of the Coptic protection letters challenges the simplistic view of rural elites as mere agents of the state, revealing their crucial role in the empire’s resilience.

In my lecture, I presented topics, arguments and findings from the PhD dissertation “Protective Interventions by Local Elites in Early Islamic Egypt” that I wrote within the ERC project “Embedding Conquest: Naturalising Muslim Rule in the Early Islamic Empire (600–1000),” led by Petra Sijpesteijn at Leiden University.

Below is the programme of the “Egyptian Christianities” series.

Banner image: O.Bachit. o Nr., a Coptic protection letter found at the Monastery of Apa Paulos, Deir el Bachit and dated to the 730s. © Koptische Ostraka Online, München, Münster 2011-2014.

Leave a Reply