On Tuesday, the 30th of September, I attended the first seminar of the 2025/2026 LAMPS Seminar Series, entitled “Coins and Consequences: The Impact of Monetised Taxation on Medieval Egyptian Society.” LAMPS, which stands for the Late Antique and Medieval Postgraduate Society, organises an annual seminar featuring postgraduate students from Edinburgh’s research in the field of late antique and medieval studies. The first seminar in this series was presented by our PhD student, Georgi Obatnin.

In his talk, Georgi shared aspects of his ongoing research and hypothesis. While I won’t divulge these details (you’ll have to wait for his dissertation to be defended!), I’d like to revisit his lecture, which delved into a significant shift we’re exploring within the framework of the Caliphal Finances project.

This shift involves tax assessment, noted by scholars in the 1980s. After 796, based on the analysis of papyrus documents, it appears that taxes were fully assessed in cash, unlike the previous system of cash and kind. The common assumption was to link this to a tax increase.

Georgi challenges this idea by examining the background of the shift. In Egypt’s agrarian economy, peasants depended on the Nile flood, crucial for understanding the cycle of flooding, harvest, and taxation. Without it, or if it was too low or high, the quality and quantity of the harvest—and thus the taxpayer’s ability to fulfil tax duties—would be negatively impacted.

Slide of Georgi’s Power-Point (credit – Georgi Obatnin)

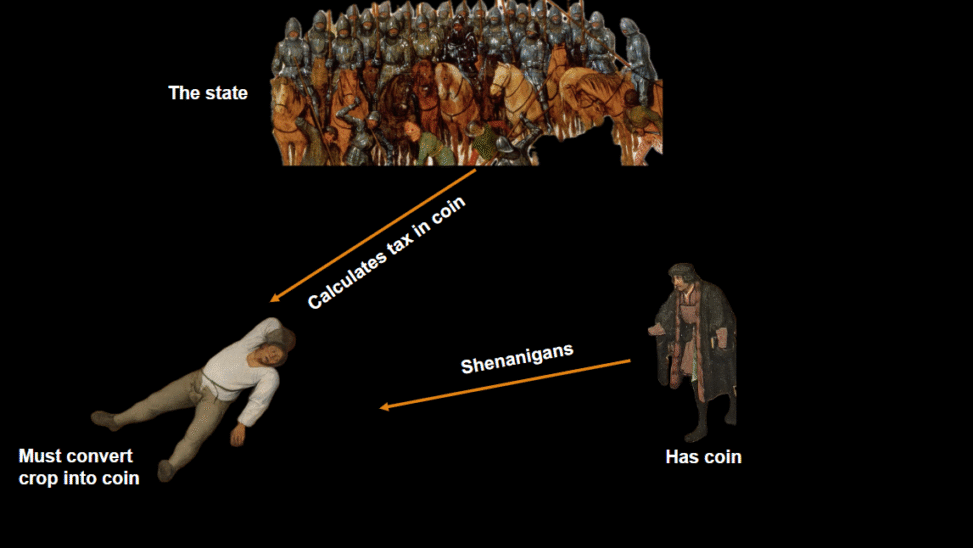

A fiscal cycle includes assessment, collection, and expenditure. Assessment involves state authorities determining ownership. Collection is when taxes are gathered, either in cash or in kind. However, Both can be done in cash or in kind. However, the relation between assessment and collection was not direct. This process is called adaeration, which means commuting the payment into cash if the assessment is made in cash. It means that you could pay with goods, say chicken, to pay your taxes assessed in cash but it entailed adaeration.

The shift Georgi investigates concerns only tax assessment, not collection. A tax assessed in cash wasn’t necessarily paid in cash. However, by introducing assessment in cash, the state forced the market to exist, as selling goods became necessary to obtain money for taxes.

Georgi also explained the Wingate Effect: in an agrarian economy, wheat is ready simultaneously each year, and taxes coincide with the harvest. At harvest time, wheat prices drop. The only way to profit is to have cash available during tax collection and wait to sell the crops.

Bearing this in mind, the shift to cash assessment was significant.

Georgi introduced middlemen—wealthy or powerful figures like monasteries, moneylenders, merchants, local elites, and tax collectors—who played a crucial role in Egyptian society. They were involved in:

- Advance sales

- Lending with harvest as collateral

- Paying taxes on behalf of others

If monetisation increased due to tax assessment in cash, it allowed more room for such activities and, more importantly, for benefitting from it.

Georgi also discussed the implications of long periods of suboptimal floods and fiscal revolts, highlighting these as crucial elements in the background. He argued that the introduction of cash tax assessment was an Abbasid State policy choice.

I’ll leave it there for today to avoid revealing too much of Georgi’s argument, but these insights should give you plenty to ponder as you await his dissertation!

Georgi Obatnin at the LAMPS Seminar

Banner Image: Slide from Georgi Obatnin’s Power-Point for the Lecture “Coins and Consequences: The Impact of Monetised Taxation on Medieval Egyptian Society.”

Leave a Reply