This series of interviews shines a spotlight on researchers working on or with the Caliphal Finances project. Each interview showcases the variety of scholarship connected to our research. This week, we feature Lajos Berkes, Greek and Coptic papyrologist, Lecturer in Ancient Greek at the at the Theological Faculty of Humboldt University in Berlin. Lajos recently participated in our workshop Abbasid-Era Fiscal Documents.

Could you briefly tell us about your background and career path?

I studied Classical Philology and History in Budapest and London, after which I wrote a dissertation at the University of Heidelberg on village administration in Egypt from the time of Diocletian to the Abbasids (284–750 AD). After completing my PhD, I was employed as an assistant professor at the Institute of Papyrology at Heidelberg University. In 2015, I was awarded a postdoctoral project by the Volkswagen Foundation to edit Greek and Coptic papyri from the early Islamic period, which included a significant outreach component. In October 2016, I gave up my postdoctoral project in Heidelberg and accepted a permanent position as a lecturer in Ancient Greek at the Theological Faculty of Humboldt University in Berlin, where I have been working ever since.

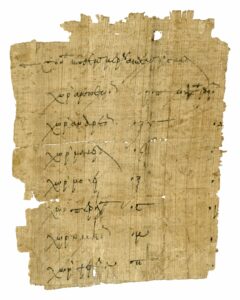

Image provided by Lajos Berkes

Can you summarise your main research areas and current projects?

I am a papyrologist specializing in late Roman, Byzantine, and early Islamic Egypt (ca. 200–1000 AD). I have extensive experience in reading Greek and Coptic papyri and have also gained familiarity with editing Arabic documents. I have also worked on and published studies addressing various aspects of late antique administrative, economic, and social history. More recently, my research interests have begun to expand into the field of early Christianity.

Of my current projects, perhaps the most relevant to readers of this blog is my work on publishing the results of the recently completed AHRC-DFG project: Documentary Snapshots from Seventh-Century Egypt: Local Responses to Regime Transitions, which I conducted with Nikolaos Gonis. This involves preparing two manuscripts. On the one hand, together with our postdoc Élodie Mazy, I am finalizing the re-edition and study of the so-called Senilais Codex, a key source for understanding early Islamic fiscality – especially the poll tax – dating from the governorship of ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀs (641–644 or 658–663/4). On the other hand, in collaboration with Esther Garel and Nikolaos Gonis, I am preparing the edition of a previously unpublished papyrological archive from the time of ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Marwān. This archive consists of Coptic and Greek documents related to Iordanes, the pagarch (i.e., overseer) of the city of Hermonthis (modern Armant), and offers important new insights into a crucial period of early Islamic history.

I am also conducting a study on the many writing exercises on papyrus from the early Islamic period and the insights they offer into multilingual scribal training in late antiquity. Furthermore, I am also excited to complete another long-standing project: the edition of seventh- and eighth-century Greek documentary and literary fragments from the monastery of Kastellion (Khirbet el-Mird), near Jerusalem. Finally, I am working on several unpublished Christian literary papyri, and – together with Gabriel Nocchi Macedo – preparing a new critical edition of the Greek S-recension of the so-called Infancy Gospel of Thomas.

What sources do you typically use in your research? What are their strengths, and what challenges do you face when using them for historical research?

As a papyrologist, I primarily focus on texts written on papyri, ostraca, and other perishable writing materials. Perhaps their greatest strength lies in the unmediated insights they offer into everyday realities. That said, using papyri for historical research is not without challenges, especially in the case of early Islamic Egypt. On the one hand, we face the perennial issue that these sources are fragmentary and often difficult to decipher. As more documents are published, our understanding of previously edited papyri continues to evolve rapidly. This means that one can never fully rely on published texts: a critical approach is essential. Dubious readings must be re-examined, as it is all too easy for entire theories to rest on shaky foundations. On the other hand, the multilingual nature of the documentation – written in Greek, Coptic, and Arabic – poses an additional challenge. While it has become increasingly common for specialists in late antique Egypt to acquire working knowledge of more than one of these languages, few scholars are equally proficient in all three or fully equipped to navigate their extensive secondary literatures. In this field, interdisciplinary cooperation is not optional but essential.

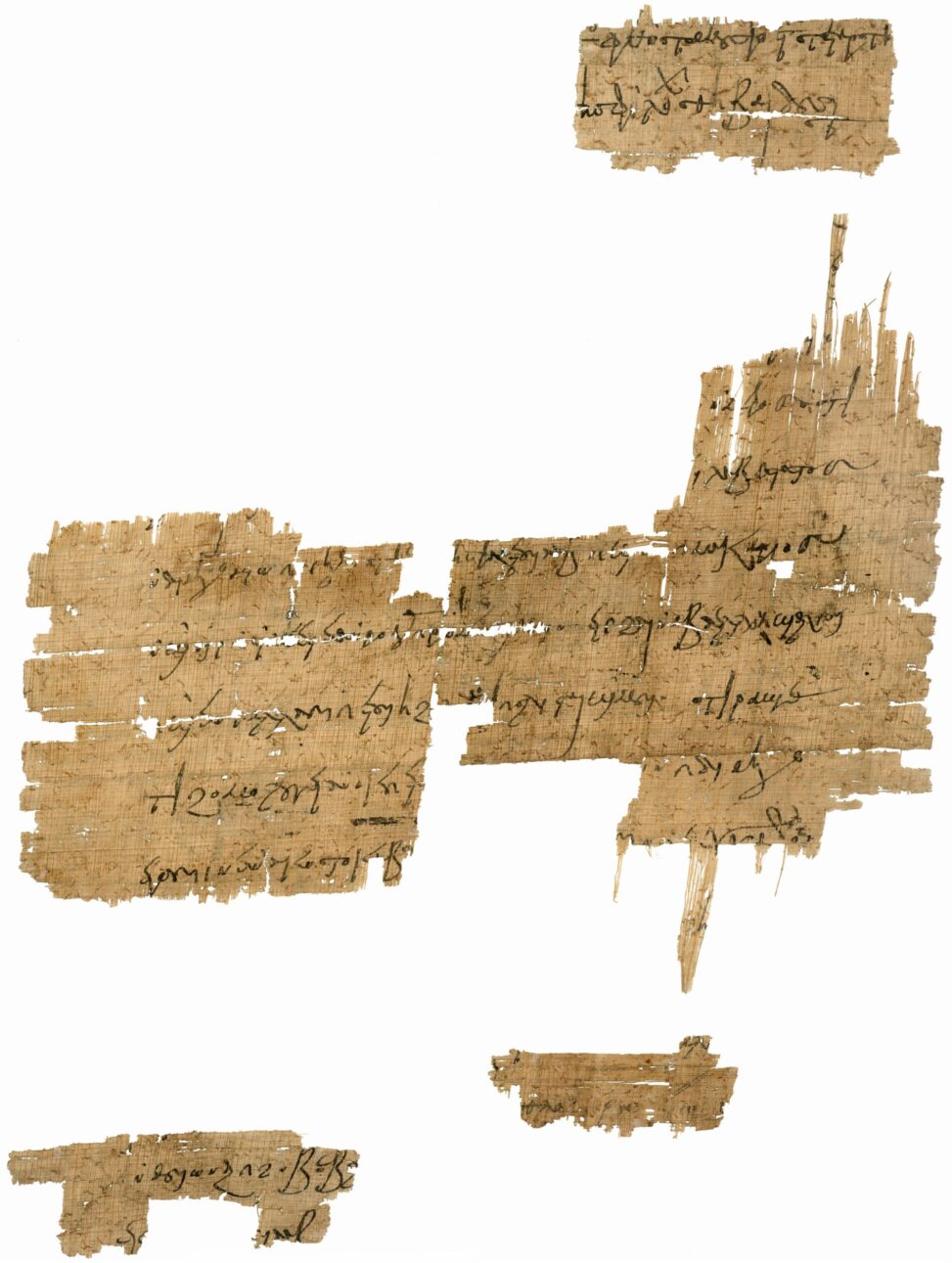

P.Heid. XI 501: Greek account listing villages belonging to the tax district of an Arab official (Fayyum, eighth century) (Foto: Elke Fuchs; © Institut für Papyrologie, Universität Heidelberg)

How do fiscal theories, practices, and institutions feature in your work? How are you approaching these topics?

Fiscal institutions and practices are omnipresent in the study of documentary papyri. Greek papyrology has developed a solid methodology for analyzing fiscal concepts, with a primary focus on chronology, terminology, and prosopography. In my research, I follow this approach while also making a concerted effort to treat Greek, Coptic, and Arabic papyri in conjunction – a strategy that has often yielded interesting results. In recent years, I have become increasingly interested in the study of scribes, as I believe that examining their roles allows us to gain a much clearer understanding of how fiscal practices operated on the ground.

In your opinion, what is a key argument or prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that needs to be challenged?

A general problem in the field is the frequent disconnect between historical and papyrological research. Papyrus editions are often cryptic to outsiders, and some papyrologists focus more on the philological analysis of texts than on their historical contextualization and interpretation, which makes these editions difficult for non-specialists to use. Moreover, papyrologists often concentrate on case studies and tend to be skeptical of broader theoretical frameworks. This attitude is perhaps understandable, given the significant methodological challenges involved in deciphering and editing individual documents or studying archives. Conversely, there is a growing trend to diminish the value of text editions as proper scholarship and to prioritize theoretical approaches instead. I believe there is ample room to establish a more productive middle ground between papyrological and historical research, one that acknowledges the importance of both philological and theoretical approaches.

A big thank you to Lajos Berkes for sharing his thoughts with us this week! To read more of these interviews with friends of the Caliphal Finances project, click here.

Banner Image: P.Heid. XI 462: A Coptic legal document from 787/788 AD drawn up between a priest and a Muslim official (Foto: Elke Fuchs; © Institut für Papyrologie, Universität Heidelberg)

Leave a Reply