In a previous post, team members Noëmie Lucas and Dalia Hussein discussed the various roles involved in the fiscal administration hierarchy of Abbasid Egypt. Using a range of source material, with a focus on tax receipts written in Arabic, they explored the complex hierarchy from the qusṭāl, who collected tax and issued receipts, to the ṣāḥib al-kharāj, responsible as head of the fiscal administration for tasks like transferring collected taxes from the province to the central treasury in Iraq. In this post, I (Eline Scheerlinck) will highlight an official appearing in Greek and Coptic documents under the title of zygostatēs. There may be a connection between this official and the qusṭāl of the ninth-century documents discussed by Dalia and Noëmie, which we’ll examine at the end.

One goal of the Caliphal Finances project is to edit documents related to the fiscal system to broaden the source base for this project and the field in general. Together with Jennifer Cromwell from Manchester Metropolitan University, I am preparing an edition of a small Coptic list on papyrus from the Cambridge University Library. This list records three men with the title of zygostatēs alongside two other men. This prompted a deeper examination of the zygostatēs office, its history, and its role in Early Islamic, and of course particularly Abbasid, fiscal practice.

The office of zygostatēs was established in the 4th century CE, and the meaning of the word, “weigher,” aptly describes the role: they were responsible for weighing solidi or golden coins and assessing their value. Originally attached to cities, they later served as treasurers for large landowners, such as in Oxyrhynchus and the Fayyum, and engaged in various financial transactions beyond weighing coins. By the mid-seventh century, Greek papyri indicate that the zygostatēs had fiscal responsibilities. Several 7th-century receipts note tax payments “through the order of the zygostatēs”: dia pittakiou tou zugostatou.

The early 8th-century archive of Basileios, district administrator of Aphrodito, includes references to zygostatai. Two appear repeatedly in the fiscal account P.Lond. IV 1412 as officials facilitating tax payments from Aphrodito and surrounding villages to the treasury (P.Lond. IV p. 81). The editor of this account still considers coin weighing and payment assessment part of their duties (P.Lond. IV p. 85). The account P.Bal. 287, written in Greek in 725 and found at the monastery of Apa Apollo of Deir el-Bala’izah, records three zygostatai linked to districts along the Nile Valley, seemingly associated with payment orders (pittakion). In the 7th and 8th centuries, zygostatai appear as officials mainly involved in transferring taxes from districts to the provincial treasury, with their original weighing function possibly still part of their duties.

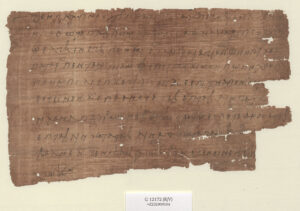

P.Christ.Musl. 16, letter from village authorities to the district administrator, about the taxes of the year 140/758. National Library of Austria, Vienna.

Although published Greek papyri don’t document zygostatēs activities after the first half of the 8th century, Coptic papyri trace them into the early Abbasid period. P.Christ.Musl. 16 (image above), a Coptic letter from 758, addressed by the head of a Fayyum village to Yaḥyā b. Hilāl, the district administrator, mentions a zygostatēs named Chaēl. The letter states that it provides a list of daily tax payments in response to an enquiry from the district administrator, although the list itself is not preserved. For a detailed exploration, see our post “Please Find Attached the List”: Insights in Early Abbasid Fiscal Administration from a Coptic Letter, which includes an English translation. While the interpretation of the letter is not always straightforward, it seems that the senders of the letter had sent an amount of taxes to the local treasury (tablion) from where it would be sent to Fusṭāṭ to the provincial treasury. The zygostatēs then, is mentioned in connection with this local treasury and could very well be interpreted as the official either at the head of it or in another way connected to it, as we have seen that his responsibilities seem to be related to transferring collected taxes to the central treasury. Here, the zygostatēs is not depicted as directly collecting taxes but as engaging at a subsequent stage after taxes leave the village, aligning with the absence of zygostatai as issuers of tax receipts.

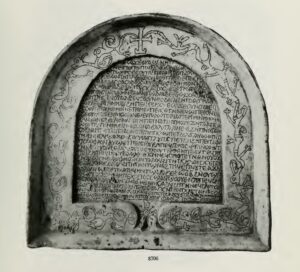

The latest attestation of a zygostatēs is on a Coptic funerary inscription dated 786 (SB Kopt. 781, l. 15: “Kosma zygos(tatēs)”), located in the Coptic Museum in Cairo. My search for further zygostatai in Greek and Coptic papyri from the Abbasid period has reached a temporary halt, though I hope for future discoveries (if any readers know of later references to this official, please reach out!).

So what is the connection between the zygostatēs and the qusṭāl? The qusṭāl is primarily known as a tax collector in ninth- and early tenth-century Arabic tax receipts from Ushmunayn or unknown provenience. It has been argued that qusṭāl derives from zygostatēs through Syriac, although another link with Greek would be from augoustalis, itself from the Latin augustalis. Whatever the case may be, while both played roles in Abbasid fiscal practices, particularly in tax collection, these roles were not identical. In Arabic receipts, the qusṭāl receives taxes directly from taxpayers, whereas the zygostatēs seems involved at a later stage, during intra-provincial tax transfers.

SB Kopt 781: Coptic funerary inscription on a marble stele, mentioning Kosma the zygostatēs on l. 15. Coptic Museum in Cairo, 8727. Image: Plate LV in O.Cair.Monuments.

This brief exploration of the zygostatēs in late antique and early Islamic Egypt highlights their evolving role in financial and fiscal practice as well as the complex networks of agents, mechanisms and procedures that constituted the Egyptian fiscal system at any given moment.

Banner image: Zygostates Alleniana. Photo credit Jorge Gastin. Image accessed at https://orchidroots.com/display/summary/orchidaceae/216173/ on 13th April 2025. The orchid genus zygostates is said to be named after the official, because the projections on either side of the column of these flowers were thought to resemble a balance. I’ll leave it to the reader to judge the aptness of the name.

Coptic and Greek documents in this post are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”.

This post has been written by Eline Scheerlinck.

Leave a Reply