This series of interviews shines a spotlight on researchers working on or with the Caliphal Finances project. Each interview showcases the variety of scholarship connected to our research. This week, we feature historian Alasdair Grant from the University of Hamburg. Alasdair is part of the SCORE project’s team, with whom we have been collaborating since the early days of Caliphal Finances, for example, in the context of our co-organised workshops “Trouble with Taxation.” Alasdair is also a contributor to this blog, and we are delighted to publish his interview this week!

Could you briefly tell us about your background and career path?

I grew up in a quiet, monocultural corner of Aberdeenshire, where my early interests centred around the architecture and history of the many castles in the local area. (My first job was as a tour guide in one of them.) I had the good fortune to attend a school where Latin and Classical Greek were taught, but where ‘History’ passed within a year or two from the Romans to the Industrial Revolution. Ever the contrarian, I wanted to study the bit in between, and in 2011 I left for the University of St Andrews with the intention of becoming a specialist in the Latin literature of early medieval Britain.

I never forgot Greece and Rome, however, and the Tin Islands continued to tussle with shores of the Mediterranean for my affections. As soon as I discovered the bequest of the Byzantinist Sir Steven Runciman in the university library, I fell in love with the complex and capricious world of crusader Greece. Feeling self-conscious about my level of Greek, however, I decided to focus at first on the northern Italians, who played such a major role in the history of Byzantium and the Crusades; this formed the topic of my first publications. As a postgraduate, I finally plunged myself confidently into the Aegean and wrote a doctoral thesis at Edinburgh on captives and slaves from the ever-shrinking world of late Byzantium, since published as Greek Captives and Mediterranean Slavery, 1260–1460.

Alasdair (Credit: Marie Helen Ferdelman)

During my master’s degree at Oxford, I had the opportunity to take an intensive beginner’s course in Arabic; I decided it was a chance I couldn’t pass up. Four years later, I had a similar opportunity to take up Classical Armenian via St Andrews, which I similarly couldn’t miss. I was never sure what role these languages, if any, would have in my career, but in late 2020 I saw an advert for a job at the University of Hamburg. Hannah-Lena Hagemann was looking for someone to work on Armenia as part of her new project, ‘Social Contexts of Rebellion in the Early Islamic Period’ (SCORE, 2020–26). Nearly five years later, the rest is historiography: my current role is as a postdoctoral Research Associate in the project, which is now into its final year. Since 2024, I have in addition been a Young Academy Fellow of the Academy of Sciences in Hamburg, and, since the beginning of 2025, I have also worked as acting assistant to the chair of Byzantine Studies at the University of Mainz.

What is your current role, and what does it involve?

In the SCORE project, I work as part of team that examines a range of case studies focused on the eighth century CE: my colleagues focus on the Khārijites, Zaydīs and provincial notables, respectively, while I work on a series of revolts by the Armenian nobility under Umayyad and Abbasid rule. Unrest in the early Islamic Empire tends to be read reductively and prescriptively as the product of religious difference or tribal tensions; a key objective of SCORE is therefore to (re-)insert socioeconomic analysis into this rather under-developed field of study. I try to account for a whole range of factors in my research, including the Church, landscape, demography, and narrative patterns, but the red thread running through everything has been taxation – and specifically the question of who gets to control the extraction of wealth.

During my time in Hamburg, I’ve also tried out what might be described as ‘teaching-led research’, convening courses on Christians under Muslim rule, trade, and rebellion. I’ve especially enjoyed some of the more speculative conversations we’ve had: How important is dogma to religion? When does rebellion become revolution? Was there capitalism before industrialisation? The experience has pushed me to explore new literature and, more importantly still, to clarify and more clearly express my own ideas in writing and speech.

Can you summarise your main research areas and current projects?

My main research interests lie in the socioeconomic history of the eastern Mediterranean and Caucasus. I am particularly interested in times and places where my main context of study, the Christian East, was in interaction with Islam and/or Western Christendom. In terms of subject matter, I started with the military and commercial expansion of Latin Christendom, then moved to captivity and slavery (the subject of my PhD), subsequently rebellion, and in future I hope to undertake a project on historical demography. The vagaries and insecurities of the current job market have been challenging, but they have at least forced me to keep my interests broad: my first academic job, post-PhD, involved curating an exhibition on Scottish–Greek connections at the time of the Greek Revolution (1821–32), and I continue to research and publish on this topic when I have time.

As SCORE comes to its conclusion, I am trying to bring together my work of the last few years to write a second monograph, provisionally entitled Armenian Rebels in the Early Islamic Empire, 630–900. This book pursues two main aims: first, to contextualise and analyse afresh the four major and several smaller rebellions that took place in this period; second, to relate this context and analysis to the question of state formation within the early Islamic Empire. Recently, for example, I have become particularly interested in the relationship between tax, rent, military service and the developments formerly known as feudalisation, which has sparked an ongoing series of rich conversations with the Caliphal Finances team and Edinburgh colleague, Nik Matheou. In parallel to this, I am also involved in editing a couple of multi-author volumes: one, Between Rebels and Rulers in the Early Islamicate World: Power, Contention and Identity came out early this year (2025) with Edinburgh University Press (co-edited with Hannah-Lena Hagemann); another, on Armenia, is in progress, as are two themed issues emerging out of our second SCORE project conference, ‘How Rebellion Ends’.

What sources do you typically use in your research? What are their strengths, and what challenges do you face when using them for historical research?

The historian of medieval Armenia faces two systemic challenges: one is the paucity – or, better, uneven nature – of the sources; the other is the way in which these sources have been and are read. Armenia lacks the papyri of Egypt, and it is unlikely that its climate has preserved documents like those discovered in west Central Asia. It does, however, boast a rich tradition of sacred and secular literature, some of which was written during or close to the time of the events and persons that it describes. That said, scholarship has traditionally privileged narrative historiography at the expense of all other genres, and some of those historiographical texts have received far more attention than others. In Armenia, historiography emerged overwhelmingly from the patronage of powerful noble families, sometimes being written by members of them, and should be understood as representing their class and partisan biases.

In scholarship on rebellion in Armenia, especially (but not only) that written under the Soviet Union, these texts were traditionally invoked to tell a story of popular resistance against foreign imperial oppression. Recent work in the Anglophone and Francophone worlds, however, has tended to stress plurality among the Armenians and to privilege examples of cross-cultural contact and fluidity. Both models are ideological and reflect the cultural imperatives under which they were and are constructed. A further problem is that scholarship written in Armenian and Russian is barely read by scholars in the Atlantic world, who are consequently poorly informed about what their colleagues have already done and are still doing. To some extent, scholarly differences also concern questions of Armenian exceptionalism or singularity and hence also touch upon nationalism; but the degree to which Armenia was typical or exceptional in the history of the early Islamic Empire will be further illuminated only when Armenia can be properly compared with other provinces: for this, we will require a series of structural concepts and definitions, and they will likely need to be constructed in dialogue with (or even derived from) other, better theorised fields.

Mount Ararat and Little Ararat from Sałmosavank‘, Armenia (Credit: Alasdair Grant)

In your opinion, what is a key argument or prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that needs to be challenged?

Early Islamic Studies is a field heavily based on philology and focused on the intellectual history of terms for and narratives about (1) confessional groups and (2) administrative institutions. These issues have their place, but there is a real risk that the entire historical endeavour is reduced purely to questions of source criticism and discourse analysis – and, indeed, the focus on these two subjects reflects the emphases of the sources themselves. Fiscal history is a victim of these biases: tax is, surely, an economic institution, but early Islamic taxes seem to be studied as if the most important thing about them were the etymology of their name. When we try to understand the form and function of these taxes, we assume that we cannot say anything that we cannot find in our sources; but those sources are themselves, of course, open to multiple and contradictory interpretations. We must therefore stop obsessing over taxes and start seriously studying tax.

The prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that most needs to be challenged, therefore, is that economic structures can be studied without economics. At its simplest, this means reinserting expenditure into the history of taxation, where issues of assessment and collection usually occupy far greater scholarly attention. An early medieval state did not invest in assessing and collecting taxes unless it wanted to spend them on something, and if we paid a little more attention to Francia or Wales, we might stop taking the very existence of the early Islamic fiscal system for granted, let alone its complexity.

This bias towards the levying of tax reflects, in my understanding, the effects (and costs) of the ‘Cultural Turn’. In the 1960s and ’70s, it looked like History was going to become a team-based social science, but a wave of source scepticism and existential angst meant that this direction was all but abandoned and has never since been taken back up. Since the 1980s, therefore, we have tended to prefer cultural readings of history (e.g., the effect of taxation upon language of just government) over economic readings (e.g., the tax-to-GDP ratio in the early Islamic Empire). The reality, however, is that most of us would not even know how to attempt to approach the second issue, while anyone can have a go at the first; rather dishonestly, we consequently sometimes claim that the first type of question is more important, when in fact both matter.

We are, however, unlikely to work out how to bring economics back into early Islamic tax history unless we look beyond Islamic Studies. We should bring lessons from the study of other pre-modern fiscal systems to bear on the early Islamic Empire, so we can model how things may have looked when we have no evidence. Where we do have evidence, we should be using it to test models and assumptions brought from elsewhere. History, in short, should start with questions, not sources; and if it does start with sources, it should certainly not end with them.

A big thank you to Alasdair Grant for sharing his thoughts with us this week! To read more of these interviews with friends of the Caliphal Finances project, click here.

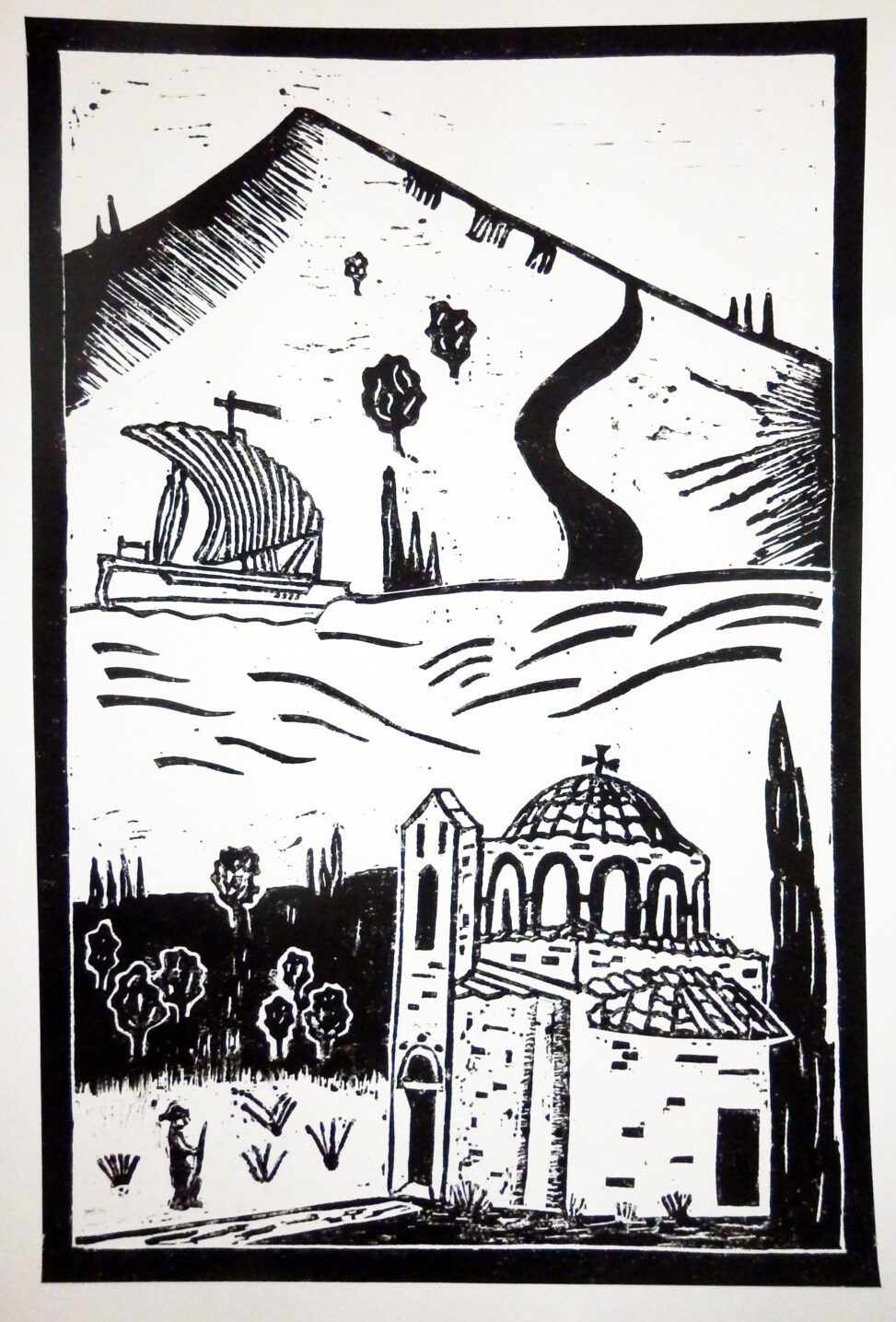

Banner image: Lino Cut Specially Designed for the Cover for Greek Captives and Mediterranean Slavery (Edinburgh, 2024) (Credit: Ann-Marie Grant)

Leave a Reply