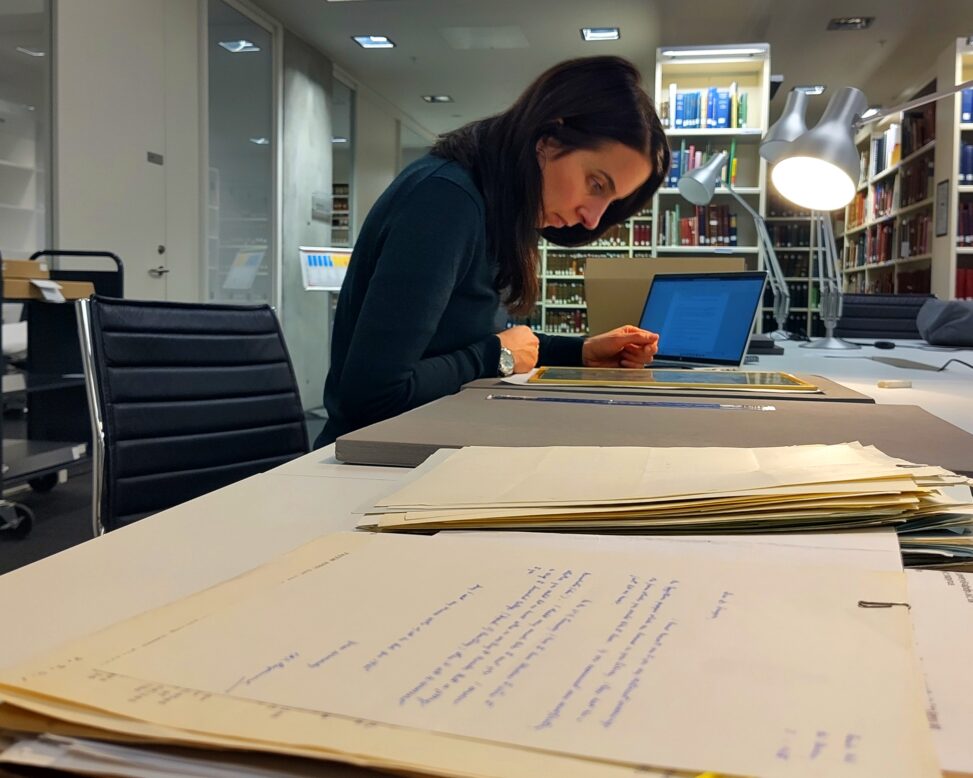

On 11th December last year, PI Marie Legendre and I, postdoc Eline Scheerlinck, left before sunrise for a three-hour train journey north to the Sir Duncan Rice Library of the University of Aberdeen. In the preceding months, I had been in contact with colleagues at the University of Aberdeen’s collections, particularly Senior Information Assistant Michelle Gait. With her help, I was able to both uncover much about the history and contents of the papyri in the Special Collections as well as, together with my Caliphal Finances team members, identify an Abbasid fiscal receipt in Arabic.

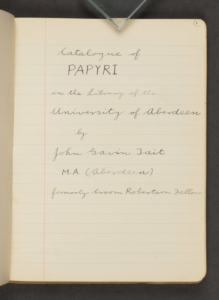

We have already published on our blog a short post on the papyri at Aberdeen, in which I touched upon some of the work that had been carried out on the collection in the first half of the 20th century, specifically the attempts to catalogue the entire collection of papyri in all languages by John Gavin Tait during the second and third decades of the 20th century. Tait had won a scholarship that allowed him to work on this project after graduating in Classics and Mental Philosophy at Aberdeen. Most of what we know about what happened in terms of storing and studying the papyri during this period comes from the nine notebooks filled by Tait at the time.

University 621/1, Tait, John Gavin. Catalogue of papyri, p. 5. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

We learn, for example, that many of the papyri did not remain in Aberdeen continuously, as certain fragments or groups of fragments were sent to various specialists in the UK to study the papyri for their own interest or to provide feedback on their contents and other notable aspects. For instance, in 1916, several Greek literary papyri were taken to the classicist and poet John Maxwell Edmonds (1875-1958) in Cambridge, where they were also placed in new glass frames. In 1919, they were returned to Aberdeen by John Gavin Tait himself, who had left Aberdeen for Oxford for a time to learn papyrological skills from Bernard Grenfell (1869-1926), one of the most celebrated UK papyrologists of the era.

The Arabic papyri in the collection were sent to David Samuel Margoliouth (1858-1940), Laudian Professor of Arabic in Oxford at the time and editor of the Arabic papyri in the John Rylands Library in Manchester. He likely sent the Aberdeen Arabic papyri back in 1923, as we have excerpts from his letter detailing the results of his examinations. These excerpts were copied by Tait into his notebooks, which also indicate that the letter was written on 10th January 1923. I quoted Margoliouth’s somewhat lukewarm overall evaluation of the collection in my first post on the Aberdeen papyrus collection.

The Abbasid fiscal receipt in the collection, while a single document of a common type, is a valuable part of our project’s source material, as it can be compared with many others of its type to contribute to broader analyses and pattern recognition. Marie presented her work-in-progress edition of the Aberdeen tax receipt on Monday 13th January at our first lecture in the IMES Seminar Spring lecture series: “‘They have come to a place where there is no one who can read them.’ The many lives of the Aberdeen papyri from Egypt to Python.”

In those early decades, the Coptic papyri were sent to Scottish coptologist Walter Ewing Crum (1865-1944), prolific editor of Coptic papyri and ostraca, as well as the compiler of A Coptic Dictionary (still a key reference today). At that time, Crum was living in Bristol. He also maintained a private collection of papyri and ostraca from Egypt, from which he made donations to colleagues and institutions during his lifetime. He donated ostraca to the library of the University of Aberdeen after Tait had assisted him by sending a Coptic papyrus from the collection for study:

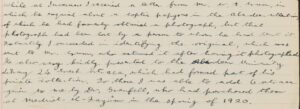

While at Inverness [at home on vacation], I received a letter from Mr. W.E. Crum, in which he enquired about a Coptic papyrus in the Aberdeen collection, of which he had formerly obtained a photograph, but that photograph had been lost by a person to whom he had lent it. Fortunately, I succeeded in identifying the original, which was sent to Mr. Crum, who returned it after having it photographed. He also very kindly presented to the Aberdeen University Library 24 Greek ostraca, which had formed part of his private collection.

University 621/8, Tait, John Gavin. Catalogue of papyri, p. 13. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

From the context of the notes, we understand that Tait was describing events that happened in 1920. The papyrus sent by Tait to Crum might have been the magical text later edited by Crum in 1922 (“La magie copte: Nouveaux textes.” in Recueil d’études égyptologiques dédiées à la mémoire de Jean-François Champollion à l’occasion du centenaire de la lettre à M. Dacier relative à l’alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques. Paris: Champion, pp. 538–544). In a footnote, Crum acknowledges the help of the collection’s librarian that allowed him to have the papyrus photographed. Crum seems to be referring only to the lost photograph, rather than to Tait’s assistance in sending him the papyrus after the photograph was lost. Korshi Dosoo, currently one of two principal investigators of the project Corpus of Coptic Magical Formularies at the Julius Maximilian University Würzburg, is preparing a reedition of the papyrus in a forthcoming publication.

Crum was not the only scholar who donated ostraca to the collections due to a personal favour from or relationship with Tait. His papyrology teacher at Oxford, Bernard Grenfell, also gifted six ostraca to the collection, as Tait recorded in his notebook:

To these I was able to add six ostraca given to me by Dr. Grenfell, who had purchased them at Medinet-el-Fayûm in the spring of 1920.

University 621/8, Tait, John Gavin. Catalogue of papyri, p. 13. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

University 621/8, Tait, John Gavin. Catalogue of papyri, p. 13. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

Tait’s notebooks provide much information about the lives of the papyri during the first 20–25 years after they were donated by the widow of their original collector, James Sandilands Grant Bey. However, the archives of the Special Collections at the Duncan Rice Library in Aberdeen also contain fascinating documents that reveal the later history of the collection.

On our one-day visit, Marie and I tried to view as many papyri as we could, but we also explored the library’s archival material related to the collection, particularly documents from the 1960s and 70s.

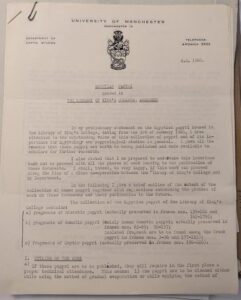

I learned that serious attempts had been made in the 1960s to catalogue and edit the Coptic papyri in the collection by Eve A. Jelínková-Reymond, a British-Czech Egyptologist. After completing her Egyptological studies in Prague, Reymond left the city after the Second World War and pursued further studies in Belgium, France, and the UK. She specialised in later Egyptian languages and scripts, edited papyri in Demotic, and eventually became a lecturer and reader in Coptic at the University of Manchester. An archive of her personal and professional papers is now held there. In 1965, Jelínková-Reymond, who signed all her letters in the Aberdeen archive using only her last surname, proposed a plan to the Library Committee to publish the hieratic, Demotic, and Coptic papyri in the collection.

She had examined all the papyri in person in 1964, and her proposal included technical conservation work such as cleaning and reglazing the papyri. Reymond offered to handle both the technical and philological aspects of the project. Her proposal also requested financial recompense for her efforts, including accommodation in Aberdeen.

Eve A. Jelínková-Reymond (1923-1986): proposal for the publication of the Egyptian-language papyri. 8th February 1966. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

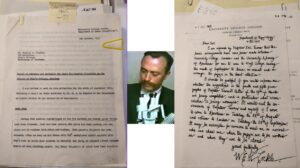

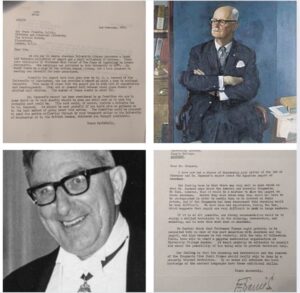

At the time, the Librarian, Douglas Simpson, sought advice from knowledgeable colleagues in the UK. First, he wrote to Frank Francis, Director of the British Museum, asking for input on Reymond’s plans, how the library should proceed, and what the project might cost. Simpson also raised the issue of how Reymond would access the papyri for her research (letter of 3rd February 1965):

“The [Library] Committee would be prepared to send the entire collection by road transport either to the University of Manchester or to the British Museum, whichever you thought preferable.”

Frank Francis advised against this approach (letter of 18th February 1965):

“We feel that it would be a mistake to allow the papyri to leave Aberdeen. We have also had experience, during the war, which suggests that papyri are very difficult to pack in large numbers.”

Francis did not provide more specific reasons for his recommendation but advised Simpson to hire a technician or restoration specialist for the cleaning, restoration, and mounting of the papyri. He also indirectly advised against letting Reymond handle the technical work:

“By no means all scholars who have knowledge of the ancient languages have these additional skills.”

Aberdeen Librarian Douglas Simpson to Frank Francis, 3rd February 1965. Frank Francis to Douglas Simpson, 18th February 1965. University Collections, University of Aberdeen. Portrait of Douglas Simpson by Alberto Morocco. University of Aberdeen.

The second person Simpson consulted was Eric Gardner Turner, a Greek papyrologist at University College London, who had published the Greek papyri in the collection in 1939. Turner arranged for Mr. Cockle, Greek papyrologist himself, and more importantly, a technical specialist who had worked on papyri for Turner at UCL, to travel to Aberdeen to clean and remount the entire collection. Aberdeen would cover rail fare, accommodation, and “a month’s salary at a rate of something like £70 or more, plus an honorarium” (In his letter of 9th March 1965, quoted here, Turner estimated the total cost at £150). This would also include the expense of new sheets of glass. Turner believed Cockle could complete the work within a month.

However, as often happens in such projects, Turner grossly underestimated the time required. In September 1965, Cockle managed to clean only 28 of the 220 glass frames in the collection. In his report dated 5th October 1965, Cockle described the condition of the collection:

“The great part of the dirt adhering to these papyri is the dirt and dust of the Egyptian desert, and it appears that when the collection was originally relaxed and mounted some forty years ago, very little of this dirt was removed. However, since that time, due to the excessive heat in their storage place in the librarian’s room, many of the wooden bearers of the frames have warped, many glasses have cracked, binding strips have come off, and the papyri [have] become exposed to the harmful influence of heat and dust.”

Cockle also detailed his work and made recommendations for the future storage of the papyri.

W.E.H Cockle, Report 5th October 1965. W.E.H. Cockle to Douglas Simpson, 7th July 1965. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

It remains unclear whether Cockle was able to return to Aberdeen to continue his work. Although Reymond visited the collection again, her plan to publish the Egyptian-language papyri, beginning with the Coptic texts, never came to fruition. Correspondence in the library’s archive reveals unfortunate misunderstandings between Reymond and Aberdeen library staff during the 1960s and 70s.

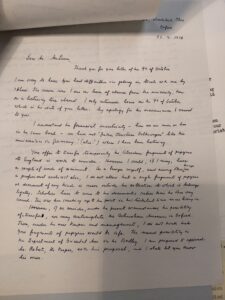

However, by the end of the 70s, it seemed that both Reymond and the library were still keen on publishing the papyri. In 1978, Reymond wrote to Colin McLaren, who held the position of Archivist and Keeper of Manuscripts at the library. McLaren had apparently offered to send the papyri to England for her to study. Reymond strongly opposed this:

“As a lawyer myself, and among other things as a professional archivist also, I do not allow that a single fragment of papyrus or document of any kind is move [sic!] outside the collection to which it belongs legally. Scholars have to come to the documents rather than the other way round.”

Somewhat contradictorily, she added that if the papyri were to be sent to Oxford, where she was based at the time, they should be sent to the Bodleian Library rather than the Ashmolean Museum.

Eve Reymond to Colin McLaren, 13th July 1978. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

Although the publication of the non-Greek papyri at Aberdeen did not progress as planned, a significant step was taken in 1975 to make them more accessible to scholars without requiring either the papyri to travel or scholars to visit in person. In October 1975, the library received a letter from Greek papyrologist Revel Coles at the University of Oxford. He informed the library about the “International Photographic Mission,” an initiative backed by UNESCO with the aim of establishing photographic negative archives of published Greek papyri in papyrological centres: Brussels, Cologne, Oxford, and Cairo. The project sought to send out teams to produce the large number of negatives required, allowing institutions to maintain their own set of negatives while also contributing to centralised archives. In his letter of 31st October 1975, Coles explained that one advantage of this approach was that “having pre-existing negatives speeds up the business of supplying prints to scholars for their research.”

Looking back, it seems the mission was not fully realised. The project’s main focus seems to have been photographing the collection of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where, according to the website of the “International Photographic Archive of Papyri,” approximately 6,000 published Greek papyri were photographed in the 1970s and 80s. The fact that the Aberdeen collection was included in this initiative seems almost coincidental. When Coles wrote to the library in the autumn of 1975, the project had some funds remaining, which needed to be spent before the year’s end. While photographing a large collection would have exceeded the available resources, a smaller collection, such as Aberdeen’s, was feasible within the budget.

An even more determining factor may have been that Coles’ in-laws resided in Monymusk, Aberdeenshire, and he planned to visit them in December anyway. Although the larger mission primarily focused on photographing published Greek papyri, Coles offered to photograph the entire Aberdeen collection, including unpublished material. As he explained, still in his letter of 31st October 1975:

There are, I believe, rather more papyri than Eric Turner actually published; we would photograph all the inedita as well if you were agreeable, but only in duplicate—one set for yourselves and one to join our Oxford archive—since it is harder to keep control of unpublished material when negatives go out of the country.

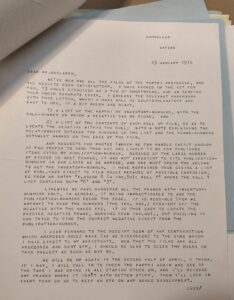

Coles and his team, which included his wife and two students, completed the work. On 23rd January 1976, Coles wrote to Archivist Colin McLaren, confirming that the negatives had been processed and sent to Aberdeen from Oxford. He noted:

“I have packed up the set for you, 13 rolls disguised as a tin of shortbread, and am sending them under separate cover.”

Revel Coles to Colin McLaren, 23rd January 1976. University Collections, University of Aberdeen.

These photographs, taken with a 35mm Nikon camera, preserved black-and-white images of the unpublished Arabic papyri. Thanks to these photographs from 1975, as well as Margoliouth’s notes copied by Tait in his notebooks in 1923, both digitised by colleagues at the Special Collections of the University of Aberdeen, we were able to identify an Abbasid fiscal receipt. Our PI Marie Legendre presented this receipt and her edition-in-progress of it during our lecture in the IMES Seminar Spring 25 on 13th January.

This visit to the University of Aberdeen’s Special Collections not only shed light on the intriguing history of the Aberdeen papyri but also underscored the enduring value of meticulous archival work. By piecing together the lives of these documents and the scholars who studied them, we continue to uncover connections that enrich our understanding of the past while paving the way for future research. This work also reminds us that historical documents are not static relics; they are dynamic sources of insight, whose stories are continuously rewritten as scholars engage with them anew.

Leave a Reply