This series of interviews shines a spotlight on researchers working on or with the Caliphal Finances project. Each interview showcases the variety of scholarship that is connected to our project’s research. In November 2024, the Caliphal Finances team had the pleasure of spending two days with Matthew Gordon and Eugénie Rébillard. In this interview, you learn more about Matthew Gordon’s research.

Could you briefly tell us about your background and career path?

I completed, in May of this year (2024), 35 years of university teaching. I began my academic career at Boston College (1989-1994) and the Rhode Island School of Design (1992-1994) before taking up a tenure-track position in the History Department at Miami University, a public institution in Oxford, Ohio. I was raised in Beirut, Lebanon (1958-1975), the son of two former faculty members of the American University of Beirut. Following a two-year stint with the Peace Corps in Marrakech, Morocco, I moved to New York City, where I eventually received my Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from Columbia University (1993). I have been very happily married to Susan Wawrose for 35 years; we have two grown children, Jeremiah (31) and Katharine (28).

Photo by Matthew Gordon

Can you summarise your main research areas (and current projects)?

My principal field is the social and political history of the medieval Islamic Middle East, with a particular interest in early Abbasid culture and society, the history of Samarra, slavery in early Islamic society, and Egypt under the Tulunids. I have published two monographs, The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (2001) and Ahmad ibn Tulun, Governor of Abbasid Egypt (2021); an edited volume, Concubines and Courtesans: Women and Slavery in Islamic History (2017); and served as a co-editor of a team translation of the works of al-Yaʿqūbī (The Works of Ibn Wadih al-Ya‘qubi, An English Translation, Brill, 2018). I have also published a number of research articles, book reviews, and short textbooks, including The Rise of Islam (Westwood, CT., 2005). I am presently at work on two projects: a co-translation, with Mathieu Tillier, of al-Kindī’s Tasmiyat Wulāt Miṣr, and a monograph tentatively entitled Al-Balawī and the Tulunid Household, a study of elite families and their networks in the early Abbasid era. I remain committed, as well, to the study of slavery as a central social and economic feature of Middle Eastern history in the early Islamic period.

|

|

What sources do you typically use in your research? What are their strengths, and what challenges do you face when using them for historical research?

My research draws mainly on edited texts produced in Arabic by scholars, historians, poets, and essayists writing across Islamic history but mainly in the first centuries of the Abbasid period. For different projects, I have drawn on a variety of such works: the Ta’rīkh of al-Ṭabarī and other related chronicles and works of geography (Samarra and the Turkic military); Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī’s K. al-Aghānī, al-Tanūkhī’s Nishwār al-muḥādara, and other adab works (the qiyān and Abbasid-era culture and slavery more generally); and, now, the writings of Ibn al-Dāya and al-Balawī, along with later works, particularly those of al-Maqrīzī (Ibn Ṭūlūn and his household). Neither a numismatist nor a papyrologist, I rely as well on the invaluable work of fellow scholars in both fields as well as art historians, archeologists, and epigraphists. We are fortunate indeed to have a wealth of material culture from the Abbasid period to draw on, in good measure as a check on the written works. A good number of edited documents from Tulunid Egypt have been made available since the nineteenth century and bear close reexamination, and I very much look forward to the appearance of new editions that allow us to develop a fuller appreciation of this period of Egypt’s history.

Tulunid dinar, © Stephen Album Rare Coins https://en.numista.com/catalogue/pieces86587.html

How do fiscal theories, practices, and institutions feature in your work? How are you approaching these topics? In your opinion, what is a key argument or prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that needs to be challenged?

The field of fiscal history is new to me. In my work on the Tulunid era, I have addressed salient questions, particularly as they relate to Ibn Ṭūlūn’s decision, in his capacity as governor, to upend fiscal and political relations with the Abbasid imperial center. But from discussions with the ERC Caliphal Finances team in Edinburgh (November 13-14, 2024) and my own work, both in translating al-Kindī’s Wulāt and reading accounts of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn’s tenure in office (254-270/868-884), I am struck by how many questions remain to be resolved, regarding Egypt but the fiscal history of the caliphate as well. Regarding the fiscal administration of Egypt, in particular, I look forward to the results of the work being carried out by the ERC team. I would close with a recent comment by Petra Sijpesteijn (from her chapter, “The Early Islamic Empire’s Policy of Multilingual Governance,” in the new volume, Navigating Language in the Early Islamic World, Brepols, 2024):

“This field [empire studies] has shown the fallaciousness of trying to ‘clean up’ the fuzziness of historical processes in such environments by replacing the complex interplay of trial and error and the back and forth of administrative developments that typically involve government bureaus and officials across the governmental hierarchy with the tidy assumption of a single order and a top-down command structure.” (p. 56).

I read the comment to mean that for historians of the Abbasid era, a best approach combines social and fiscal history, alongside an abiding appreciation of the inclinations – ideological, political, cultural and religious – of the writers of the medieval texts.

A big thank you to Matthew Gordon for sharing his research with us this week! To read more of these interviews with friends of the Caliphal Finances project, click here.

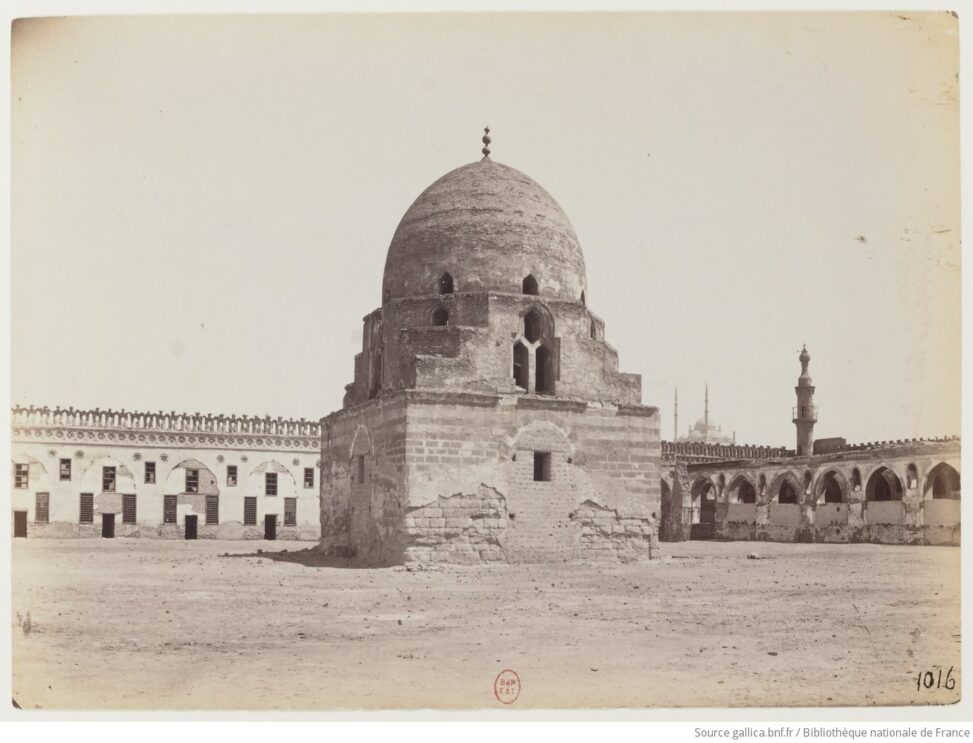

Banner Image: Ibn Tulun Mosque by Facchinelli, Beniamino (1839-1895). Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, BOITE FOL B-EO-1717 http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb43671734v

Leave a Reply