This blog post pursues the exploration of one fiscal-related narrative. After having investigated the making of this khabar (Part 1), I will focus on its interpretation within the broader structure of al-Yaʿqūbī’s work.*

The khabar under investigation:

Al-Rashīd pursued officials (al-ʿummāl), wealthy landowners (al–tunnāt), village chiefs (dahāqīn), owners of estates (ḍiyāʿ), land agents (al-mubtāʿīn lil-ghallāt), and holders of tax-farms (al-muqbilīn), for they owed accumulated sums (amwâl mujtami’a). He put ‘Abdallāh b. al-Haytham b. Sām in charge of collecting the money from them, which he did by means of various forms of torture This was in the year 184. Al-Rashīd came down with a severe illness in that year, but recovered from it. When al-Fuḍayl b. ‘Iyād visited him and saw that people were being tortured for payment of the land tax (kharāj), he said: “Relieve them, for I heard the Messenger of God say: ‘He who tortures people in this world, God will torture him on the Day of Ressurection.’” So al-Rashîd ordered that torture should not be used against people, and torture was banned from that year on. (al-Yaʿqūbī, Taʾrīkh, The works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī, vol. 3, 1163)

When taxation talks about just rule

From Taxation to the “king’s body”

It is noteworthy how this khabar shifts from the issue of taxation to the question of the king’s body, with the mention of al-Rashīd’s illness and the potential torture he might face on the Day of Resurrection. Al-Rashīd’s illness could be interpreted as divine punishment for the unjust actions of his delegate, ‘Abdallāh b. al-Haytham b. Sām, who tortured people to collect taxes. Although it was not al-Rashīd himself who ordered the torture, his delegate’s actions reflected on him due to the delegated power.

In the medical thought of the time, disease was often seen as a reflection of an imbalance in the humors of a person, caused by an excess, deficiency, or corruption of one of the humors. This brings to mind the concept of the “King’s Two Bodies” by Ernst Kantorowicz, where the illness of Hārūn al-Rashīd can be viewed as a manifestation of an imbalance at the state level. Since the king’s body is both natural and political, the illness in the political body manifests in the natural body.

A Discourse on Just Rule

The purpose of this khabar is linked to a discourse on just rule. However, this conclusion is reached from an atomistic perspective, considering the khabar in isolation without fully accounting for its immediate textual environment. As I noted in Part 1 of this blog post, the khabar is part of a section in al-Yaʿqūbī’s Taʾrīkh that includes two accounts about the oaths of allegiance of al-Amīn and al-Ma’mūn—one brief account before the khabar and a much longer one afterward (spanning seven printed pages of Arabic). In this context, the khabar about taxation and al-Fuḍayl’s guidance to al-Rashīd can be seen as an interpolated clause in a broader narrative about oaths of allegiance.

This placement suggests that the khabar might be evidence of al-Rashīd’s just rule, as it demonstrates his willingness to listen to the advice of the ‘ulama and correct wrongs. The fact that this story is situated between two accounts of oaths of allegiance further reinforces the idea that it contributes to a discourse on good governance. Indeed, bay’a documents are particularly valuable for studying the nature of the relationship between rulers and the ruled.

Bay’a as a Contract

Let’s take a moment to consider the concept of bay’a. Bay’a is not just an “oath of allegiance”; it is a contract between the ruled and the rulers, as evidenced in al-Yaʿqūbī’s section. The Arabic root of bay’a implies a transaction between two parties, similar to a sale.

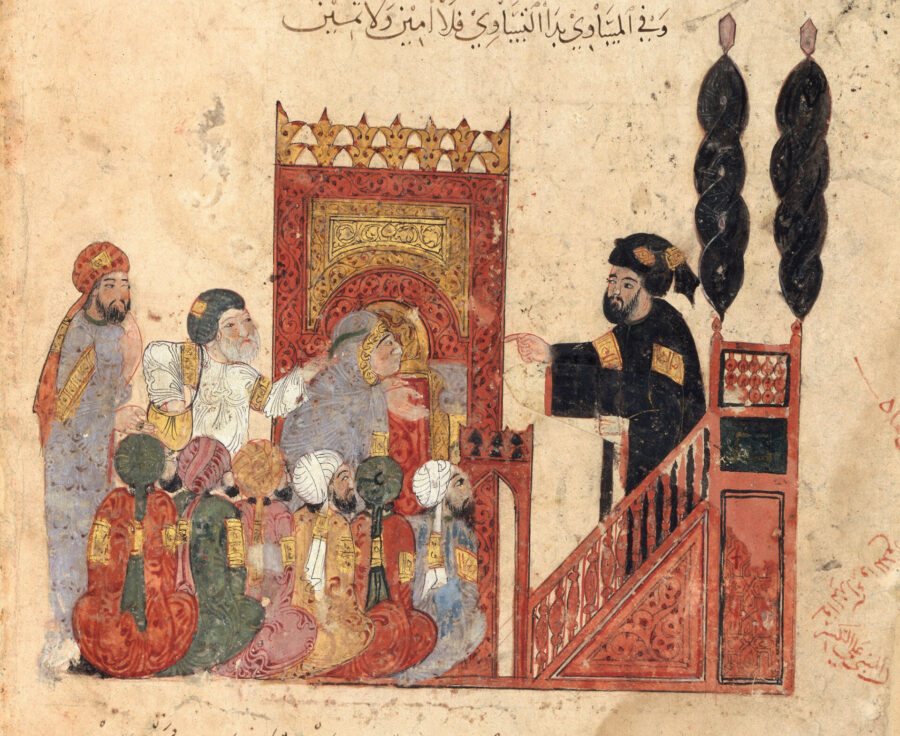

Ali Receiving the Bay’a, illustrated folio from a manuscript of Maktel-i Ali Resul of Lami‘i Chelebi – end of sixteenth century. © cc – Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, The Edwin Binney, 3rd Collection of Turkish Art at the Harvard Art Museums

Before the khabar about tax arrears, we find the bay’a of the ruled toward al-Ma’mūn:

Al-Rashīd had the oath of allegiance (al-bay’a) taken to his son al-Ma’mūn as heir apparent after (his brother) Muḥammad (al-Amīn) in this year 183. The oath of allegiance to him was received from all the people, even from the people of the markets. Eight years separated the oath taken to Muḥammad and that taken to al-Ma’mūn (2:501)

This bay’a binds the ruled to the ruler, committing them not to revolt and not to question his legitimacy. Conversely, the ruler is also bound by this contract, as evidenced in the documents al-Amīn and al-Ma’mūn wrote during the pilgrimage. These documents, dictated by al-Rashīd, outline the conditions of each son’s power and emphasize the binding nature of the oath.

These documents state the conditions of the power of each of them. It is supposed to be an oath that binds. That is why we read the following sentences, for example in the kitāb of al-Amīn

وجعل لي البيعة في رقاب المسلمين جميعا

[Hārūn al-Rashīd] has made the oath of allegiance to me obligatory for all Muslims

واخذ له علي وعلى جميع الناس البيعة

I make the oath of allegiance to him binding upon myself and upon all the people.

And also at the end of the document, just before the mention of the witnesses:

فان اضمرت او نويت غيره فهذه العهود والايمان كلها لازمة واجبة على وقواد امير المومنين وجنوده واهل الآفاق والامصار وعوام المسلمين براء من بيعتى وخلافتى وعهدى

If I ever harbor any such thought or intend anything other than this, all of these covenants and oaths shall ensue and take their effect on me; and the officers of the Commander of the Faithful, his armies, the people of the provinces and garrison cities, and ordinary Muslims shall be released from the oath of allegiance to me, my caliphate, and my covenant

The bay’a emphasizes the conditions of the contract, that are stipulated in the oath and the vocabulary speaks, in a way, for itself; not only the term of bay’a, you also have the term of ‘ahd (covenant) as in the extract. In a way, we can say that a bay’a states the duties of the subjects and the duties of the rulers. In that context, the fact that the narrative about taxation is to be found within this section can explain that, like a bay’a, taxation binds the rulers and the ruled. This is the reason why it enables to factor in a discourse on just rule.

Kitāb al-Kharāj, Incipit, Feyzullah 1287

This khabar is like an interpolated clause in a general discourse about governance. It also emphasizes the figure of Hārūn al-Rashīd as a religious ruler who could listen to advisers and tried to ensure good governance or just rule after him (though he massively failed). The caliph had the right to levy taxes but also the duty to ensure that it was done with respect of the taxpayers and their abilities to pay because excessive taxation is a sign of unjust rule. At this point, we can of course mention the treaty of Abū Yūsuf, which offers developments about all of this. A close study of fiscal-related akhbār in narrative sources can also provide a lot of understanding of the role of taxation from the point of view of good governance or just rule.

Taxation and Governance

The narrative about taxation can be seen as part of this larger discourse on governance, much like the bay’a itself. Just as the bay’a outlines the duties of both the subjects and the ruler, taxation also binds the rulers and the ruled. This connection supports a broader discussion on just rule, highlighting that while the fiscal system was not questioned, criticisms were directed at how taxes were collected and distributed.

During the early Abbasid period, significant debates occurred regarding the redistribution of fayʾ (taxes collected from kharāj lands and non-Muslims). An interesting example of this debate can be found in the epistle of the judge of Basra, ʿUbayd Allāh b. al-Ḥasan al-ʿAnbarī (m. 168/785), addressed to Caliph al-Mahdī and preserved in Wakiʿ’s Akhbār al-Quḍāt. This text emphasizes the importance of defining those entitled to a share of the fayʾ and advocates for its redistribution to the entire Muslim community.

From a historian’s perspective, taxation is an inclusive political theme when assessing just rule, as it concerns the entire society. Governance can be evaluated from various viewpoints: the taxpayer, the beneficiary, or the ruler. The collection of taxes and the redistribution of revenues were central to the state’s prerogatives, as reflected in political wills such as the one al-Manṣūr wrote to his son al-Mahdī:

“Give Muslims the share of their wealth to which they are entitled, increase for them their share of the fay’, pay them their stipends regularly, and provide their living allowance promptly, year by year and month by month. Attend to the cultivation of lands by easing the burden of the land-tax. Win the people over with pleasing conduct and reasoned policy.” (2/474)

Bibliography of the studies mentioned in Part 1 and 2

El-Hibri, Tayeb. Reinterpreting Islamic Historiography, Harun al-Rashid and the Narrative of the Abbasid Caliphate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Kantorowicz, Ernst. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton University Press, 1957.

Tor, Deborah. “God’s Cleric: Fuḍayl b. ʿIyāḍ and the Transition from Caliphal to Prophetic Sunna,” in Islamic Cultures, Islamic Contexts: Essays in Honor of Professor Patricia Crone, ed. Behnam Sadeghi, Asad Q. Ahmed, Adam Silverstein, and Robert Hoyland. Leiden: Brill, 2014, 195-228.

Banner Image: BnF, Arabe 5847, f. 18v, ark:/12148/btv1b8422965p

*This blog post derives from a presentation I gave on the 28th of October 2021 for the online conference Expectations of Justice and Political Power in the Islamicate World (ca. 600-1500 CE), organized by the ERC project Embedding Conquest.

This post has been written by Noëmie Lucas.

Leave a Reply