As part of my research on Abbasid fiscal history and historiography, I examine fiscal-related narratives to understand how they inform us about fiscal practices and its history. This blog post explores one of these narrative units, known as akhbār (singular: khabar), and investigates how a better understanding of its making can impact our knowledge of fiscal history.

The khabar is taken from al-Ya’qūbī’s Taʾrīkh*. It recalls a story set during Hārūn al-Rashīd’s reign in 184/800 in Iraq. Coming back to Baghdad after spending some time in Raqqa, Hārūn al-Rashīd’s took the following decision:

Al-Rashīd pursued officials (al-ʿummāl), wealthy landowners (al–tunnāt), village chiefs (dahāqīn), owners of estates (ḍiyāʿ), land agents (al-mubtāʿīn lil-ghallāt), and holders of tax-farms (al-muqbilīn), for they owed accumulated sums (amwâl mujtami’a). He put ‘Abdallāh b. al-Haytham b. Sām in charge of collecting the money from them, which he did by means of various forms of torture This was in the year 184. Al-Rashîd came down with a severe illness in that year, but recovered from it. When al-Fudayl b. ‘Iyād visited him and saw that people were being tortured for payment of the land tax (kharâj), he said: “Relieve them, for I heard the Messenger of God say: ‘He who tortures people in this world, God will torture him on the Day of Ressurection.’” So al-Rashîd ordered that torture should not be used against people, and torture was banned from that year on. (al-Yaʿqūbī, Taʾrīkh, The works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī, vol. 3, 1163)

This khabar first interested me due to the names mentioned at the beginning of the account, which provide information about the taxpayer society or at least give some indication about those from whom taxes were collected. Even though there is no geographical context in al-Yaʿqūbī’s when this khabar is reported, the fact that dahāqīn are mentioned leaves little doubt about where the action took place: most probably in Iraq. Moreover, al-Ṭabarī and al-Dīnawarī’s accounts confirm this assumption, as will be revealed below.

About the protagonists of the khabar:

- Hārūn al-Rashīd is an Abbasid caliph who ruled between 170/786 and 193/809. He is the father of al-Amīn and al-Ma’mūn who were opposed to each other in the succession of their father during the fourth fitna. Concerning taxation, let’s note that the famous Kitāb al-Kharāj of Abū Yūsuf was dedicated to Hārūn al-Rashīd.

- ‘Abdallāh b. al-Haytham b. Sām: Unfortunately I have not found any information about him so far.

- Al-Fuḍayl b. ʿIyāḍ (m. 187/803) was a hadith transmitter and a zāhid who is notably known for giving ascetic addresses to Hārūn al-Rashīd. And this is what he does in that account, he rebuked the caliph’s behaviour and recalled to him the divine punishment to be expected by those who act wrongly on earth.

Al-Fuḍayl acts like a religious instructor using a saying of the Prophet: من عذب الناس في الدنيا عذبه الله يوم القيامة . This hadith, at least its meaning is also mentioned for example by Abū Hilāl al-‘Askarī (m. v. 400/1010) in his book of Caliphs who left it to a qadi’s judgement specifically in his preamble focusing on the fairness of the ruler; and the question of equity ( الظلم ظلمات يوم القيامة). It reminds us that, in the genre of what is called “mirror for princes”, a link is made between good decisions of the ruler and good governance or just rule.

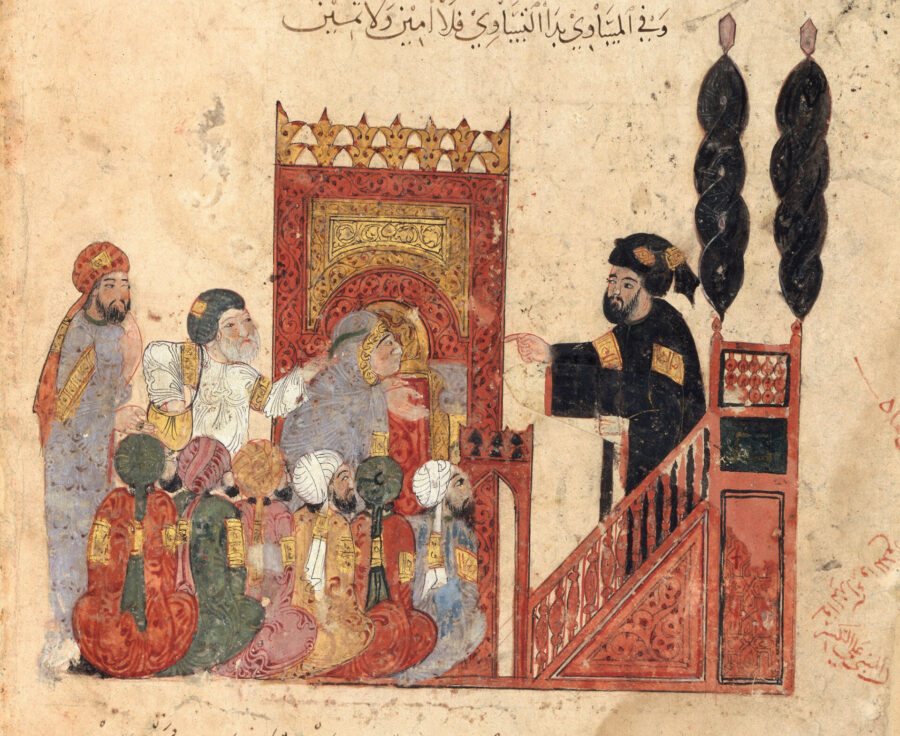

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

The “making” of a fiscal-related khabar

About the Situation of the khabar within al-Yaʿqūbī’s Taʾrīkh

The account is located in a section, which mostly deals with oaths of allegiance and Hārūn al-Rashīd’s succession:

- First, in 183, the oath of allegiance taken to al Ma’mūn as heir apparent after his brother al-Amīn is reported and it is indicated that this oath (bay’a) was received from all the people.

- Then a mention of al-Rashīd appointing religious scholars to instruct his sons

- Then comes the khabar that is the focus of this blog post and occurred in 184

- Then in 186/802, Al-Rashīd took residence in al-Rafiqa (that is in Syria, in Raqqa)

- The same year he led the pilgrimage accompanied by his two sons and in Mecca he dictated to both documents about the succession that are reproduced entirely in al-Yaʿqūbī’s Taʾrīkh.

Transmission

There is no isnād that tells us the story of the transmission of this khabar and of any of this section as well. That is of course coherent with the rest of the Tārīkh of al-Yaʿqūbī. To have an idea of the possible transmission canals from which al-Yaʿqūbī received the account, we have to look at his introduction. He explains there that he composed his work relying on authorities (ashyākh) that preceded him (Al-Yaʿqūbī, Taʾrīkh, vol. 2, 2: ʿulamāʿ, ruwwāt, aṣḥāb al-siyar wa-l-akhbār wa-l-taʾrīkhāt). Then, he gives the list of those authorities (wa-kāna man rawaynā ʿannu mā fī hadhā l-kitāb (al-Yaʿqūbī, Taʾrīkh, vol. 2, 3)) and I believe that among the authorities he mentions, this account could have been transmitted by one or few of the following:

- al-Madāʾinī (d. e. 223/843)

- al-Haytham b. ʿAdī (d. between 206/821 and 209/824)

- al-Wāqidī (d.207/822), a historian active during the reigns of Hārūn and al-Ma’mun.

- Isḥāq b. Sulaymān b. Ali al-Hāshimī who held various offices under Hārūn al-Rashīd (for example governor of Mosul (776), governor of Egypt (793-794), in 795 he is appointed in Basra to his father’s old position of governor at the time of the event. He wrote a Kitāb al-Taʾrīkh wa l-siyar.

- Or Abu l-Bakhtari Wahb b. Wahb al-Qurashi (d.200/815) who served as a judge under Hārūn al-Rashīd and was a traditionist, genealogist and historian.

The information we have about these authorities, their dates of death, where they spent time, and what themes and periods they are known to have transmitted about allow me to assume that they could have transmitted at some point the khabar about Hārūn al-Rashīd and the arrears of taxes.

Intertextuality

I tried to trace this khabar in other sources to assess possible intertextuality. According to what I have been able to read, this khabar, in this form, is not present in any other medieval works. However, elements of it can be traced elsewhere.

Let’s first consider the first part of the khabar:

Al-Rashīd pursued officials (al-ʿummāl), wealthy landowners (al–tunnāt), village chiefs (dahāqīn), owners of estates (ḍiyāʿ), land agents (al-mubtāʿīn lil-ghallāt), and holders of tax-farms (al-muqbilīn), for they owed accumulated sums. He put ‘Abdallāh b. al-Haytham b. Sām in charge of collecting the money from them, which he did by means of various forms of torture.

The decision of Hārūn al-Rashīd to collect arrears of taxes is mentioned in both al-Tabari’s Taʾrīkh and in al-Dīnawarī Kitāb al-akhbār al-Ṭiwāl:

| Al Ṭabarī (vol. 8, 272 & Trans in vol. 30, 173) | Al-Dīnawarī (p. 370) |

| Among the events taking place during this year was Harun’s entering the City of Peace in Jumada II, returning thither from al-Raqqah by boat down the Euphrates 629 When he reached the city of Peace, he instituted punitive measures against the people regarding arrears of taxation from previous years and, according to what has been mentioned, ‘Abdallah b. al-Haytham b. Sam assumed the task of extracting these arrears, by imprisonment and flogging. |

فلما كان أوان الحج، حج، فقضى نسكه، وجعل منصرفه على الرقة، فأقام بها، وولى يزيد بن مزيد أرمنية، ثم قدم من الرقة سنة أرب وثمانين ومائة حتى وافى مدينة السلام، ونزل قصره بالرصفة، وأخذ عماله بالبقايا، ثم سار من مدينة السلام

|

- In al-Ṭabarī’s, the account is less detailed about those subjected to these punitive measures. We only read al-nās where al-Ya’qūbī mentions different groups of people. It is usually very complicated to know to whom the collective “al-nās” refers in narrative sources. In this specific case, the cross-reference gives us a hint of it. The appointment of Abdallāh is also mentioned, as well as the fact he resorted to violence to achieve his goal.

- In al-Dīnawarī(d. 896)’s text, the account of the decision of Hārūn al-Rashīd, the appointment of ʿAbdallāh, and the use of violence is summarized in a very short sentence: “He took arrears of taxation from his ‘ummāl” focusing only on the decision of al-Rashīd regarding the arrears of taxes. Nothing is said about violence or the person in charge of the recovering of the taxes.

One can however observe that the account in both cases is inserted into a similar group of short information about Hārūn al-Rashīd’s reign: mostly his whereabouts, from al-Raqqa to Baghdad notably, and some appointments he made.

As for the second part of the khabar, notably the interaction between Hārūn al-Rashīd and al-Fuḍayl b. ‘Iyad, I could not find it anywhere else, at least with these wordings and contextualization.

When al-Fuḍayl b. ‘Iyâd visited him and saw that people were being tortured for payment of the land tax (kharâj), he said: “Relieve them, for I heard the Messenger of God say: ‘He who tortures people in this world, God will torture him on the Day of Ressurection.’

Accounts about an interaction between both men can, however, be found in other sources. The earliest after al-Ya’qūbī’s Taʾrīkh is Murūj al-dhahab of al-Mas’ūdī where we learn that the caliph summoned religious authorities notably Sufyân b. Uyayna, a muhaddith and faqih of the Hijaz who died in 196/811, and al-Fuḍayl. Al-Fuḍayl asked Sufyan who is the Commander of the Faithful and he pointed out al-Rashīd. The caliph wept and gave every man in the room a large sum of money that al-Fuḍayl did not accept.

As for later accounts of the purported personal interaction between al-Fuḍayl and Hārūn, Deborah G. Tor, who devoted an article to al-Fuḍayl “God’s Cleric: al-Fuḍayl b. ‘Iyād and the Transition from Caliphal to Prohetic Sunna”, explains that they “may simply be exegetical elaboration of the significance” of al-Yaʿqūbī and al-Masʿūdī’s reports. Her hypothesis seems to be right when we look at later accounts of the interaction between the ascetic and the caliph. There is a short account of an encounter between Hārūn and al-Fuḍayl in al-Tawḥīdī (d.414/1023), al-Basâ’ir al-Qudamâ’. The other accounts are actually the same adduced in several variants.

We find it in later sources like Abū Nu’aym (d.430/1038), Ḥilyat al-Awliyā, Ibn al-Jawzi (m.597/1200); ‘Uyūn al-Ḥikāyāt or al-Dhahabī, Siyar (m.748/1348). Their account is very long, with 4 printed pages in the edition of Ḥilyat al-Awliyā of Abū Nu’aym. I would like to mention one common feature of these accounts

The account is usually related on the authority of al-Faḍl b. Rabī’ (d. 207/822–3 or 208/823–4) who is a well-known figure of al-Hādī, Hārūn al-Rashīd, and al-Amīn’s reigns since he held various offices during that time. In 179/ 795-6 he was appointed ḥājib (chamberlain) of al-Rashīd so he had a privileged position to witness his public and private life. He might have been the witness of the events mentioned in al-Ya’qūbī’s work and he might have transmitted that to Abū ʿUmar al-Jarmī, who is also mentioned in the isnād of the long khabar about the interaction. Abū ʿUmar al-Jarmī was a grammarian from Basra who died around 840.

MSS 745.1–3 | Hajj certificate 17th–18th century AD. Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art (Khalili Family Trust) British Museum.

The context of the account of the encounter is the following: Hārūn was leading the hajj and was seized with spiritual doubt. Therefore, he asked for someone who could give him guidance. To sum up the account, al-Faḍl took al-Rashīd to see religious authorities of the time but no one succeeded in satisfying Hārūn’s spiritual needs. Eventually, he reached al-Fuḍayl’s house but al-Fuḍayl did not demonstrate any desire to meet with him. The meeting finally took place during which, and here I quote Deborah Tor who summarizes it in few words, al-Fuḍayl “reproves Hārūn and launches into several anecdotes, all involving the idealized and exemplary conduct of the caliphal ancestor al-ʿAbbās and of ʿUmar II, as well as an admonishment regarding the solemnity and heavy responsibility of the burden of rule and the ever-present danger – for rulers who fail to execute satisfactorily their obligations toward the Muslims – of burning in Hellfire forevermore.” (Tor, 217). Then the caliph wept. Al-Fuḍayl in the end refused to accept any money from the caliph. This admonishment and guidance regarding governance and just rule echo the khabar we find in al-Yaʿqūbī’s book even though it goes into more detail.

It seems to me that there is kind of a “model story” with regards to “a recognizable caliph-scholar interaction”. I borrow the expression to Tayeb el-Hibri. The latter mentioned the relationship between Hārūn al-Rashīd and ascetics in a section entitled “The ascetic caliph” in his book Reinterpreting Islamic Historiography, Harun al-Rashid and the Narrative of the Abbasid Caliphate, where he wrote:

The format usually runs as follows: an eminent religious scholar who has few or no ties with the state is brought before the caliph to offer his educating comments. Suddenly, the scholar takes the opportunity to make some harsh criticism of kingship and political authority in general. The scholar briskly evokes the theme of death and the horrors of the afterlife and describes the tragic transiency of human life…. (27)

What he describes matches the khabar, subject of this blog post. And I could draw a line between the khabar about tax arrears and how sources deliver an image of a pietistic caliph when it comes to Hārūn al-Rashīd (El-Hibri, 28). The khabar in al-Yaʿqūbī’s book does stress that aspect of a religious caliph and we cannot ignore it all the more so as the khabar is situated in a section where the pilgrimage is mentioned and where the behaviour of the caliph is, in a way, praised.

However, I have to consider the khabar in its entirety. When considering the first part and then the second part of the same khabar and how they interact with other sources, it looks like this account is a concatenation of two different accounts:

- A report about the decision of Hārūn al-Rashīd to collect arrears of taxes. This is the one that can also be read in al-Ṭabarī and al-Dīnawarī. This report refers to a fiscal practice for which we have evidence elsewhere and for other periods (notably in Egypt in the ninth century). It points to a challenge that the Caliphal authority was facing when it came to tax collection.

- An account of the interaction between Hārūn al-Rashīd and the ascetic al-Fuḍayl b. ʿIyad. The latter rebukes Hārūn’s decision and addresses some just rule advice.

This observation is strengthened by the difference in tone between both parts of the khabar:

- A first part that we can call quite “factual” and which stresses a political decision and an appointment.

- A second part, which reported an interaction between the caliph and an ascetic figure and recalls his sayings.

What is missing however in the sources other than al-Yaʿqūbī that I have read is the illness of the caliph and his final decision to ban the use of torture. The illness of the caliph seems to serve as a transition between the two parts of the khabar. It links the decision of the caliph about arrears, the wrong behaviour of his delegate, and the admonishment of al-Fuḍayl altogether. In Arabic, the causal relationship is noticeable by the use of ‘fa-‘ between the mention of the illness of the caliph and the beginning of the story of the interaction between Harun and al-Fudayl:

واعتل الرشيد في تلك السنة علة شديدة اشقى منها فدخل اليه الفضيل بن عياض فراى الناس يعذبون في الخراج فقال ارفعوا عنهم انى سمعت رسول الله يقول من عذب الناس في الدنيا عذبه الله يوم القيامة فامر بان برفع العذاب عن الناس فارتفع العذاب من تلك السنة.

It is not only a juxtaposition and I believe that the use of fa is here meaningful.

Here ends the first part of this blog post, stay tuned for what comes next….

Banner Image: BnF, Arabe 5847, f. 18v, ark:/12148/btv1b8422965p

*This blog post derives from a presentation I gave on the 28th of October 2021 for the online conference Expectations of Justice and Political Power in the Islamicate World (ca. 600-1500 CE), organized by the ERC project Embedding Conquest.”

This post has been written by Noëmie Lucas.

Leave a Reply