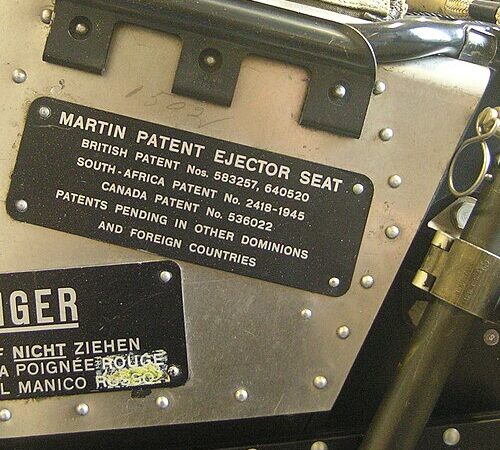

I remember the first time I realised there was a name for the feeling I had every time I prepared to open my mouth at work. The fear that this was going to be the moment when everyone realised that I had no right to be there and that I was going to suddenly lay bare the truth about my substandard thoughts. Realising that it wasn’t just me was reassuring, comforting. It didn’t make it any easier to do it, but over time I gathered evidence that I had interesting things to say and that even when I got things wrong, it didn’t trigger the University Ejector Seat. Imposter Syndrome – I accepted this without thinking too much about what it implied. I was grateful to know that I wasn’t alone in my self doubt.

Many years later I was speaking at an event for women in science. The topic of imposter syndrome came up and I listened to the audience talking about how difficult it was to maintain their confidence. All I could see were incredible, talented, clever women who were pushing themselves to be better, to grow and to learn. I started to see that Imposter Syndrome only flared for me when I put myself outside my comfort zone. Rather than being something to acknowledge and try to work around, I reframed it as a badge of honour. Celebrate this as evidence that we are pushing forwards. I was proud that I still put myself into situations where I felt that uncertainty – it was a sign I was stretching myself to improve.

Over time, I became more familiar with my roles and responsibilities. These feelings receded, only to come roaring back when I started a new role here at the University. Despite many years of success in my previous role, I felt exposed and again, nervous about confirming what I was sure everyone else suspected; that I wasn’t up to it. But this time I was equipped with the knowledge that this was a sign that I was growing again. It was going to be ok and I would start to feel like I belonged here once I had gathered enough evidence that I was a positive, contributing colleague. I felt like I had accepted Imposter Syndrome and worked out how to use it for my own benefit.

A few months in, someone in my institute asked me what I knew about Imposter Syndrome as they had heard people talking about it. “Aren’t we lucky that we don’t have this? It must be awful to walk into a room and feel like you don’t belong there.” I laughed and explained that I felt like this EVERY DAY. I was stunned that he (gentle reader, it was a man) didn’t feel like this and I asked him if he was ever in a situation where he doubted he had credibility in the eyes of others. “No, never.” My relationship with Imposter Syndrome began to change. Why was I feeling this when he wasn’t? We were a similar age, had the same qualifications, were in not dissimilar roles. Hmmm, was it possible that I had gone through the world with a different experience? (Spoiler: Yes.) Did this make me look on Imposter Syndrome with slightly less positive emotions? (Spoiler: Yes.)

I did some reading around Imposter Syndrome and looked for the first time at the power of the words. Syndrome implies a medical condition – a weakness or failing in the individual. Imposter implies a difference and sense of not belonging. Nothing in that phrase conveys what leads to imposter syndrome – the systematic undermining and excluding of some groups and individuals. I had already started to see the world differently after an encounter with Jocelyn Bell Burnell some years before when the ESOF conference was in Dublin. Rather than go to the glitzy keynote (from memory with Bob Geldof) instead I saw there was a chance to have a conversation with Jocelyn and I grasped it. There were very few of us there – perhaps a dozen – and we ranged in age from our twenties to seventies. Jocelyn asked us about our experiences in science and I noticed an interesting trend.

The youngest women were very positive, didn’t really see any discrimination, felt they were accepted in their own right. The 30-somethings were almost as convinced, but were starting to notice they were the ones having to make difficult decisions about family and work. They remarked that the insecure years when you need to give ALL to a scientific career seemed to coincide with the years when you might want to start a family. Those in their 40s were a little more blunt. They were the ones who had had to make difficult decisions and sacrifices for their careers. Those with families were expected to do the bulk of the childcare and caring (at the time I was in this group and although I was able to dodge these expectations through the support of my partner, others never allowed me to forget they were there.) The fifty-somethings were angry that although they had mostly moved through the intensity of early years child care, they were expected to pick up other domestic responsibilities (elder care now starting to feature). They were far behind colleagues who hadn’t had to make these choices and struggling to catch up. If they showed any anger or frustration they were written off as women of a certain age. Needless to say the 60 and 70-somethings were FUMING. Their pensions were impacted by the years of reduced salaries, they hadn’t fulfilled their potential and they were alarmed by what they had heard from their younger counterparts because it felt like very little had changed. Although women were now far more numerous in science, science hadn’t shifted to accommodate them.

This is what creates a sense of not belonging – it echoes the thoughts of my earlier post on welcome. You will feel like you belong if you are the same as the norm. If you aren’t, every time you walk into a room, every time you voice an opinion, every time you let your “life” show you feel your difference. As a result we lose so much.

I’m grateful for the conversation that led to the scales falling from my eyes where imposter syndrome is concerned. From that point on I’ve looked for ways to change the system, rather than the individuals who don’t fit into it. I don’t know how much difference I’ve made and I know there’s still a long way to go, but reframing imposter syndrome as a symptom of a failing system rather than failing individuals was a key moment. I was reminded of this a few weeks ago when the second of the amazing poets that this blog has featured so far spoke at the “The University and the World: Restoring Wholeness in Fragmented Times” event that featured in the Welcome blog. Pepita Mwanga, a spoken word poet and the Impact Coordinator for the Scholars Network spoke about the development of her thinking about imposter syndrome in a way that reminded me of my changing attitude. I’m delighted that she’s going to reflect with me on imposter syndrome in a companion piece to this which will appear soon.