As I move towards producing the final monograph for this project, I aim to post occasional rough (sometimes very rough) snippets of writing on all of the sites and topics that will be in the final publication. There may be typos ahead (apologies in advance).

This week I kick things off with my efforts to understand just what that strange artificial hill, the Beckton Alp is actually made of.

The Beckton Alp, one of the four main case study sites of this project, is located in the London Borough of Newham. Beckton take sits name from the Beckton Gasworks established here on the East Ham Levels by the Gas Light & Coke Company (GLCC) in 1868.

Opening 1870, the works would go onto be the largest gasworks in the world and remain today (in much reduced scale as gas storage and distribution centre). The name comes form the companies’ then Governor, Simon Adams Beck. The GLCC was established in 1812 with works in Westminster and gradually amalgamated an merged with other companies until becoming the largest gas supplier in London until its nationalisation in 1948. The gas (called ‘Town gas’ or coal gas) was produced by carbonising coal – heating it in sealed vessels – retorts whereby around 1/3 of the mass of coal was released as flammable gas that was then condensed and purified. What happens to the other 2/3 is equally interesting – the remains of the coal remained as coke while a series of other by-products were left, including coal tar and ammoniacal liquor, of which more below.

By-products

Beckton Products Works (then known as the ‘Tar and Liquor Works’) opened in 1879 on a 90 acre site adjacent to what is now the Beckton Alp and continued operating in until 1969. The opening of the works some nine years after the opening of the Gas Light & Coke Company gasworks itself was undertaken in response to the increasing realisation of the value that could be obtained from processing the two major coal gas waste products, coal tar and ammoniacal liquor. These were later supplemented by reprocessing of other by-products spent oxides (a by-product of from purifying coal gas), cyanogen liquor, and benzole.

Such substances, when further refined into different secondary materials, provided the feedstock for a huge range of industries in the East End and beyond in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There is a long and complex history to the chemical and engineering innovations involved in processing this material (e.g. Townsend 2003; Leslie 2006; Hamper 2006), but broadly speaking, coal tar formed the basis for products including: anthracene (critical in dye stuff making e.g. for aniline dyes including red alizarin), creosote (used as waterproofing/staining for wood), napthalene oil (used in pesticides), carbolic oil (phenols; made into further products like to make plastics) and light oil.

The ammoniacal liquor component was also converted to sulphate of ammonia – a key component in agricultural fertilizers, while the cyanogens were used to make the anti-caking agent, potassium ferrocynaide and the synthetic pigment, Prussian Blue. The sulphuric acid produced in the works was crucial to many different industries in East London but perhaps most notably for using in galvanising steel; galvanised steel wires were used in vast quantities by the major submarine telegraph cable manufacturers on the Thames to the west of Beckton such as W.T. Henley’s Telegraph Works and Silver’s at North Woolwich.

Prior to the opening of the works the coal tar, liquors, and spent oxides were originally simply disposed of as waste material along with waste ash and clinker, prior to innovations in synthetic chemistry in the mid-nineteenth century and the realisation that vast sums could be made from processing them. As realisation of this value grew, those making town gas like the Gas Light & Coke Company (formed in 1812) who had originally dumped or sold off these ‘residual’ by-products began to take an interest in processing them themselves. Hence the eventual opening of the Products Works in 1879.

What ultimately remains after all the complexities of all this processing and re-processing this material varies through time. This is because in such Products works almost everything was reused it seems; one waste product was almost instantaneously transformed into the feedstock for something else. Yet, inevitably there must be something left that cannot be used, most likely in the form of ashes, clinker and waste chemicals.

What lies beneath?

Samantha MacBride has called coal ash a ‘constant material reminder of our past’ in its ultimate persistence in the environment from our long-standing addiction to burning coal (. Even in an era where coal ash is now relatively rare in age absent of open coal fires or (mostly without) coal power stations it remains in vast dumps, mixed into concrete and as ‘breeze’ blocks in construction. So is in the Beckton Alp simply, only, waste ashes from both the gasworks (i.e. leftover from the carbonisation of coal to make gas) and the last remainder of the processes of value extraction of the Products Works? It would seem not.

For one thing, the Alp is heavily contaminated; Iain Sinclair once noted ‘[t]he mound, so they say, is pure arsenic.’ (Sinclair 2003). While slightly fanciful if taken literally, environmental reports do mention arsenic and other heavy metals. Yet contamination is not all that is here. Apparently thousands of tons of clay were dumped on top of the waste from the construction of the British Library, though I am yet to find compelling documentary evidence for this. That said, one source suggest the site was capped with at least 1m of clay by 1979 along with a further 0.3m of topsoil (Wood and Griffiths 1994, 99).

Further investigation as part of the proposed redevelopment plans for Beckton after the Work’s closure in 1969, commissioned a scientific study of the Alp and provide a more comprehensive answer:

The “Beckton Alps” were built up first from spent gas lime, then spent oxide and boiler ash and clinker. Spent sulphuric acid containing sulphonated hydrocarbons and other tar acid impurities has been dumped in a pit near the South end. An area near the north end was covered with “blue” spent oxide with a high proportion of Prussian Blue.

The report goes on to say:

In recent years the tip has been used for dumping soft tar and a large area consists of lagoons of tar which has hardened on the surface but is very soft underneath. Builders’ rubble has also been dumped on the tip in recent months.

(London Dockland Study Team 1973, 59)

Spent oxides are the name given to the varieties of by-products produced from purifying coal gas after carbonisation (ie. Resulting from the coal gas making process, rather than the Products Works). Different forms of this purification were developed over time but as indicated by the report, just quoted, the earliest forms used lime while later processes used iron ore. These materials removed sulphur and other materials form the gas production processes allow its calorific value to be raised and for it to be safely used.

The iron-based process spent oxides were themselves processed en mass to created sulphuric acid in the product works (Townsend 2003) but it seems that much of this material was also dumped, including at Beckton. As well as the Alp, this material seems to be located to the east of the products work. Correspondence between Kubrick’s crew and the North Thames Gas Board during the filming of Full Metal Jacket instructs them to avoid a sealed off area of the site which is marked as ‘spent oxide dump’ for example.

Commemorating contaminants

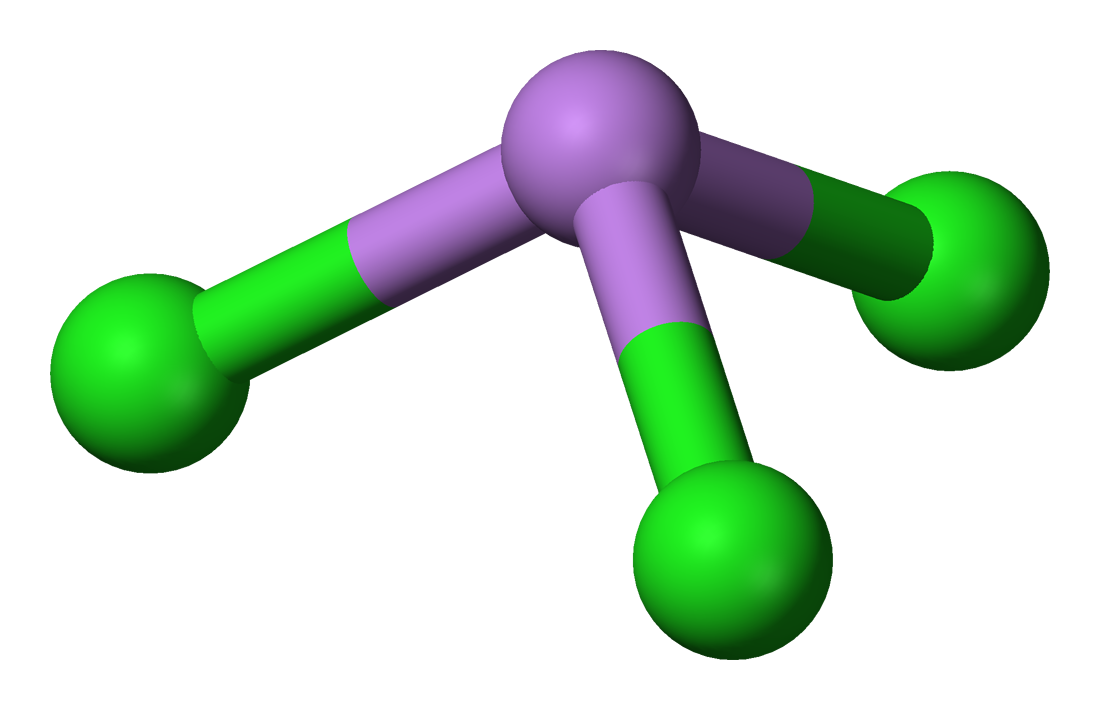

So, under the ruins of the ski slope and a rapidly developing mostly self-seeded ecosystem, the Alp – unsurprisingly – contains numerous chemical toxins. However these toxins are not simply waste but also a reminder of the vast array of products and chemical innovations that took place here. Perhaps recognising this, in an unrealised project for the ‘Big Art Project’ (a 2009 Channel 4 series) Antony Gormley proposed installing a gigantic 35 metre high molecular model of ‘arsenic petrocholride’ (most likely actually arsenic trichloride; others have said gallium arsenide) on the Alp. He said at the time: ‘I like the idea that, somehow, what was hidden beneath in molecular form could be made apparent above in sculptural form.’ (in Hanly, Smith, and Wardle 2009, loc. 00:47:23).

I can’t share the copyrighted clip showing the model of the artwork unfortunately but imagine several of these joined together and 35m high – effectively doubling the height of the Alp! If you can access Box of Broadcast through a university you can view the clip here.

Little information survives on this proposed art project but it would have been quite something! To be continued….

References:

Hamper, Martin J. 2006. “Manufactured Gas History and Processes.” Environmental Forensics 7 (1): 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/15275920500506790.

Hanly, Frank, Neil Smith, and Louise Wardle, dirs. 2009. “Big Art.” Channel 4. https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/00F74AFC?bcast=32345316.

Leslie, Esther. 2006. Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry. London: Reaktion Books.

London Dockland Study Team. 1973. Docklands: Redevelopment Proposals for East London Vol.2, Appendices. London: R. Travers Morgan & Partners.

MacBride, Samantha. 2013. “The Archeology of Coal Ash: An Industrial-Urban Solid Waste at the Dawn of the Hydrocarbon Economy.” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 39 (1/2): 23–39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43958425.

Sinclair, Iain. 2003. “A Circular Story.” The Guardian, October 25, 2003, sec. Books. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/oct/25/featuresreviews.guardianreview27.

Townsend, Cyril. 2003. Chemicals from Coal: A History of Beckton Products Works. London: Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society. http://www.glias.org.uk/Chemicals_from_Coal/.

Wood, A A, and C M Griffiths. 1994. “Debate: Contaminated Sites Are Being over-Engineered. the Case for. (Case against by c.m. Griffiths Follows).” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Civil Engineering 102 (3): 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1680/icien.1994.26765.