Sometimes the brain gets it all wrong. It misinterprets the information from one or more of the senses. This phenomenon is commonly known as sensory illusions.

Revisiting S.B., who regained his eyesight after more than 50 years of being blind. Using vision, he now recognised simple shapes and ordinary objects as well as their size. But he closed his eyes in traffic. Perhaps more complex visual information overwhelmed him. Perhaps it did not match his memories from when he was still blind. Or perhaps both. (See our blog for the scientific approach, Vision, haptic touch, and hearing and Sensory mismatch.) A related issue is that of conflicting information within and between the senses. Did S.B. show an effect on sensory illusions based on or including visual information?

When S.B. was still blind, he would have been familiar with both tactile and auditory illusions.

But what about visual illusions?

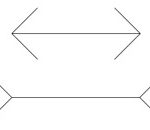

Visual experience is not necessary to show an effect on all visual illusions1. Indeed, S.B. would have encountered some of them when he was still blind. Simply because certain illusions are both visual and tactile. And S.B. would, therefore, have shown an effect on these illusions immediately after he had started using vision. For example, on the Müller-Lyer Illusion2,3.

The Müller-Lyer Illusion consist of two horizontal lines that are identical in length: one with inwards-pointing and one with outward-pointing fins. People who show an effect on this illusion, perceive the line with the outwards-pointing fins as longer than the other line. The Müller-Lyer Illusion is found both in people who are born fully sighted and in people who are born blind. As well as in children (born with very low or no vision; 8–16 years old) after only 48 hours of seeing4. But this was not the case for S.B., who regained his eyesight at the age of 525.

S.B. showed a very weak effect on the visual Müller-Lyer Illusion.

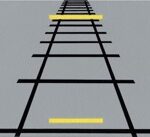

For other visual illusions, visual experience is sometimes necessary and sometimes not. An example is the Ponzo Illusion. The Ponzo Illusion consists of two parallel lines that are converging. These two lines are crossed by several horizontal lines that are identical in length. Almost like a railway track that disappears into the distance. People who show the Ponzo Illusion perceive the crossing lines as becoming shorter and shorter the more the vertical lines converge.

The Ponzo Illusion does not show and effect in people who rely on their sense of touch. And prior visual experience does not change that6. This illusion is not tactile. At the same time, the visual Ponzo Illusion is found in children (born with very low or no vision; 8–16 years old) after only 48 hours of seeing4. The illusion is visual, but prior visual experience is not necessary. In a parallel vein, the Ponzo Illusion has been translated into an auditory format. This auditory version of the illusion occurs in people who are fully sighed and wearing a blindfold. But not in people who have been blind since before they were 20 months old7. The Ponzo Illusion is not auditory without prior visual experience. S.B. who had been visually impaired from before he was two years old should, therefore, have shown an effect on the visual Ponzo Illusion immediately after he had regained vision. Or on a similar illusion.

Instead of judging the length of two lines as in the Ponzo Illusion, S.B. was asked to describe the relative sizes of four men. People who have been fully sighted since birth typically perceive the men as increasing in height. S.B. described: “They don’t look far away, it’s just as though the men were standing underneath (? the buildings). The first man looks smaller, but the last three look the same.” 5 S.B. showed a very weak effect on the visual Perspective Size Changes Illusion. (Gregory & Wallace, 1969, p. 22)

After having regained vision, S.B. would also encounter multisensory illusions that include visual information. These illusions consist of conflicting information from vision, touch, hearing, smell, and/or taste. The brain now has to decide how to deal with this. It most often turns to previous learning. An alternative would be to ignore the visual information. Indeed, multisensory illusions that include visual information do not exist without vision. And also not if the visual information is not associated with the other sensory information in a certain way, for example, the lip movements and the sound of spoken words. Prior visual experience is necessary.

Immediately after having regained vision, S.B. would not show an effect on multisensory illusions that included visual information. But his susceptibility to them would probably increase as he learnt to associate and integrate visual information with other sensory information. (See our blog for Crossmodal correspondences between the senses and Multisensory processing.) That is, if he did not close his eyes.

Now, challenge your senses.

Tactile illusions:

Auditory illusions:

- Barberpole Illusions

- Speech to Song Illusion

- Trinton Paradox Illusion and Hearing Lyrics where there are none

Visual illusions:

- Dalmation Illusion (picture and video)

- Schroeder Staircase Illusion

- Spinning Dancer Illusion

See our blog for Activities; especially 65-67.

Blog post author: Dr Torø Graven

1. Bean, C H (1938) The blind have “optical illusions.” Journal of Experimental Psychology, 22(3), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061244

2. Heller, M A, … [et al.] (2002). The haptic Müller-Lyer illusion in sighted and blind people. Perception, 31(10), 1263-1274. https://doi.org/10.1068/p3340

3. Millar, S, & Al-Attar, Z (2002) The Müller-Lyer illusion in touch and vision: Implications for multisensory processes. Perception & Psychophysics 64(April), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194709

4. Gandhi, T, Kali, A, Ganesh, S, & Sinha, P (2016) Immediate susceptibility to visual illusions after sight onset. Current Biology, 25(9), R358-R359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.005

5. Gregory, R L, & Wallace, J G (1969) Recovery from Early Blindness A Case Study. Experimental Psychology Society Monograph, No. 2. https://www.richardgregory.org/papers/recovery_blind/recovery-from-early-blindness.pdf

6. Heller, M A, & Ballesteros, S (2012) Visually-impaired touch. Scholarpedia, 7(11), 8240. http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Visually-impaired_touch

7. Renier, L, … [et al.] (2005) The Ponzo Illusion with Auditory Substitution of Vision in Sighted and Early-Blind Subjects. Perception, 34(7), 857-867. https://doi.org/10.1068/p5219

y need to physically pick up objects – ranging from those who immediately touch objects to those who are reluctant even with prompting.

y need to physically pick up objects – ranging from those who immediately touch objects to those who are reluctant even with prompting.