The brain processes sensory information through a network of crossmodal correspondences. And, it integrates multiple sensations too. (See our blog for the scientific approach, the crossmodal correspondences between the senses, Crossmodal brain plasticity and empowering of sensory abilities, and Multisensory processing.) But what it actually perceives and later processes is affected by emotions. Which in turn affects the emotions, for example, the feeling of anxiety.

This time Michal Pieniak, Institute of Psychology, University of Wroclaw, and Professor Thomas Hummel, Smell & Taste Clinic, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Universitätsklinik Dresden, demonstrate how anxiety affects the sense of smell. In his research, Michal Pieniak focuses on connections between olfaction and both cognitive and emotional functioning, and Professor Thomas Hummel on the diagnostics and treatment of olfactory / gustatory loss, the mechanisms involved in irritation of the upper airways, the olfaction in neurodegenerative disorders, and the interactions between the olfactory, trigeminal, and gustatory systems. Between them, they have more than 800 scientific publications. And have received several scholarships and awards (e.g., the 32nd edition of the START program, Foundation of Polish Science, and the European Chemoreception Research Organization (ECRO) for “Excellence in Chemosensory Research”).

The sense of smell helps humans detect dangers in their environment. For example, the smell of smoke or natural gas warns us about potential threats to our safety. If someone can’t smell these odors, they might have more accidents or injuries at home. This is a common problem for people who have lost their sense of smell1. Therefore, being able to accurately detect odors is crucial for our safety and health.

People who experience anxiety, such as generalized anxiety, tend to focus more on things that might be threatening2. This attention to threats can apply to many types of dangers, but sometimes it is more specific. For example, people with social anxiety pay extra attention to faces showing negative emotions3. However, it is not well understood how anxious people perceive smells and if their attention to threats extends from visual objects to odors.

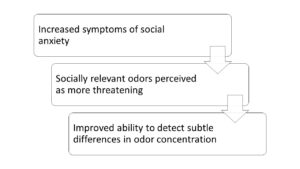

Recently, we teamed up with a research group from Macquarie University in Sydney, led by Prof. Mem Mahmut, to investigate this question. We tested 127 university students who reported their levels of social and generalized anxiety symptoms. They participated in tasks measuring their sense of smell accuracy and perception of odors. Some odors were general, like rose, turpentine, and motor oil, while others were socially relevant, like perfumes, artificial flatulence, and unpleasant body odor. We found that students with higher levels of generalized anxiety were better at detecting subtle differences in intensity of general odors than those with lower anxiety levels.

Similarly, students with social anxiety were better at sorting socially relevant odors according to their intensity, what was related to the perceived threat of these odors. This suggests that socially anxious individuals see socially related odors as more threatening, which helps them notice subtle differences in odor concentration.

Since our study was correlational, we cannot say for sure whether anxiety causes heightened smell sensitivity or if heightened smell sensitivity leads to anxiety. Additional research, including neuroimaging studies, will help us better understand the relationship between smell and anxiety disorders.

Considering previous findings and results of our study we can conclude that:

– Our sense of smell is essential for detecting environmental dangers and maintaining safety.

– Anxiety can affect how people perceive and respond to odors, with those experiencing anxiety perceiving odors as more threatening and being more sensitive to certain smells4.

See our blog for Activities; especially 43-45.

Some suggestions for further listening, reading, and watching:

Anxiety and Sensory Processing Disorder – Which Comes first?

How Anxiety Affects the Mind and Body

How anxiety warps your perception

Sensory Anxiety: Not Your Ordinary Anxiety

Sensory Problems Caused by Anxiety

_______________

1Santos, D. V., Reiter, E. R., DiNardo, L. J., & Costanzo, R. M. (2004). Hazardous Events Associated With Impaired Olfactory Function. Archives of Otolaryngol-Head & Neck Surgery, 130(3), 317-319. DOI: 10.1001/archotol.130.3.317

2Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (2005). Attentional Bias in Generalized Anxiety Disorder Versus Depressive Disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29(1), 29-45. DOI: 10.1007/s10608-005-1646-y

3Lee, H.-J., & Telch, M. J. (2008) Attentional biases in social anxiety: An investigation using the inattentional blindness paradigm. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 46(7), 819-835. DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.001

4This research was funded by the National Science Centre in Poland (grant 2022/45/HS6/00651).