Tag: 2023

Lockdown taught us that you don’t really need to be somewhere physically to get the work done, right? History student Olivia might disagree. When I started university, I didn’t really spend much time in the William Robertson Wing – the home of the School of History, Classics and Archaeology, or HCA as it’s usually known. […]

Seth is from Belgium and has recently completed his first year of studying History and Scottish History. Starting university is always daunting but doing so as a ‘Mature Student’ can be even more so. Of course, even in this case one size does not fit all, as the term ‘Mature Student’ covers anyone starting university […]

Amidst the excitement of the coronation of King Charles III, Dr Alasdair Raffe – Senior Lecturer in History – takes a look at the story of Scotland in it all. “Some aspects of the coronation of King Charles III on Saturday 6 May 2023 have been updated to reflect modern tastes – the oil with […]

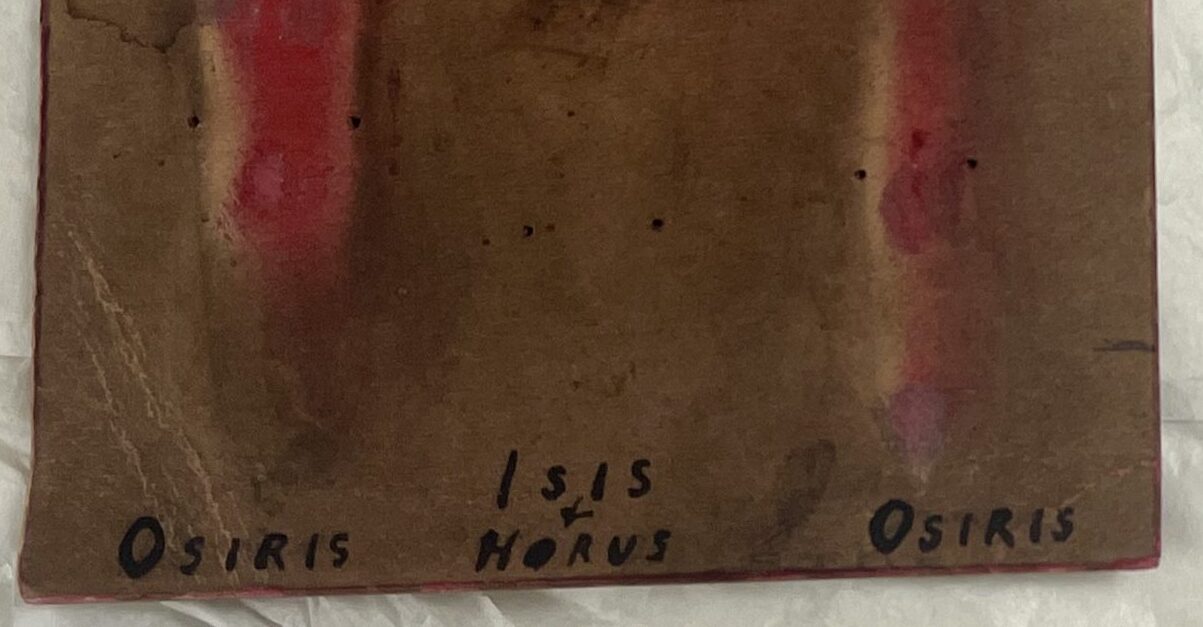

Before Indiana Jones, there was Vere Gordon Childe. The great man – Indiana Jones – recommends him to his students as he skids across a library on the back of a motorbike, but not even he had access to the Vere Gordon Childe Teaching Collection. The Vere Gordon Childe Teaching Collection is a unique collection. […]