Category: School of History, Classics and Archaeology

Rachel is a Master’s in History student. In this blog, Rachel talks about the differences between undergraduate and postgraduate study, a normal day, and the best place for lunch! When applying to graduate school, there’s the burning question that arises: “How is graduate school different from undergraduate school? And, maybe more importantly, what do graduate […]

Kit is a third-year MA History student. In this blog, Kit discusses the courses they studied so far. I started my MA in History at the University of Edinburgh in the autumn of 2021. I am now in my 3rd year (after having to take a one year interruption of study) and looking forward […]

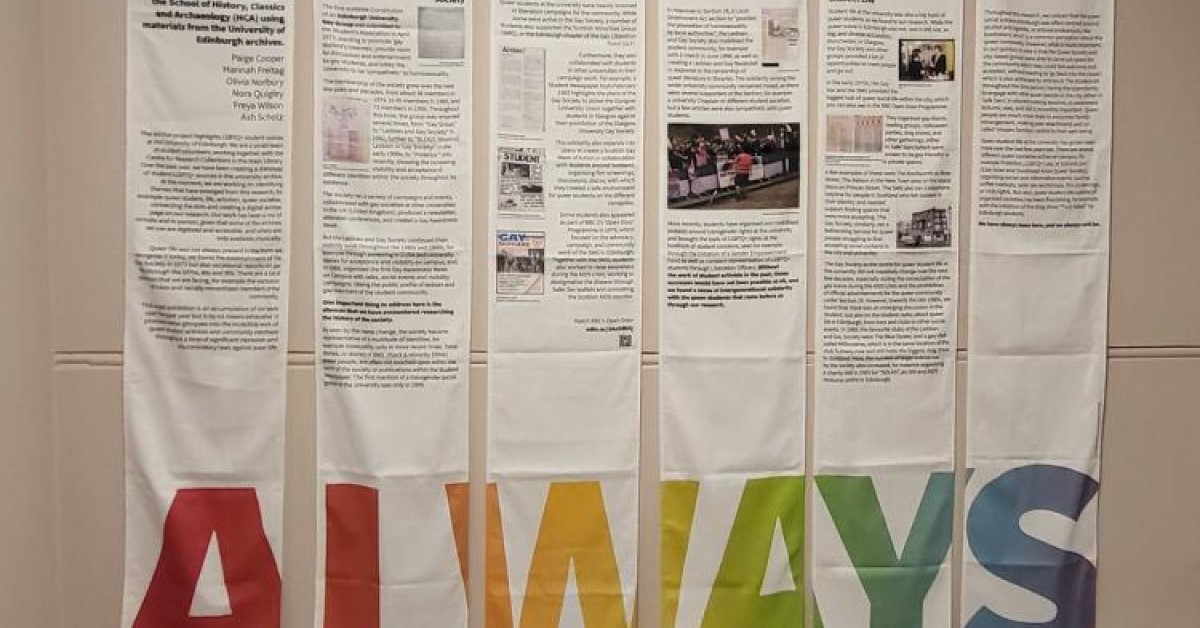

What does it mean to be queer in Edinburgh? Ash is a fourth year History and Politics student, and student ambassador. Ever since arriving at the university as a queer person, I have felt that there such a wide array of queer events, LGBTQ+ societies and groups in the city, but the amazing queer […]

Dr Henry (Indiana) Jones Jr once said, “If you wanna be a good archaeologist you gotta get out of the library!”, which is exactly what some of our first year archaeology students did recently. The School of History, Classics and Archaeology is lucky enough to have a wealth of archaeological sites on its doorstep. A […]

In this blog post, Tessa Warinner, wellbeing adviser at the School of History, Classics, and Archaeology, discusses ‘Burnout’ – a rising concern in academia. Tessa discusses what it feels like, its prevalence, impact, and signposts helpful resources for managing it. This post belongs to the Hot Topic theme: Critical insights into contemporary issues in Higher Education. I’m […]

In this post, Rose Day, Learning Technologist at the School of History, Classics, and Archaeology (HCA), highlights the HCA TEL Learn Ultra Showcase. The showcase features some of the innovative courses and provides insightful commentary from course organizers and learning technologists who played pivotal roles in their development. This post also belongs to the Spotlight on Learn […]