Category: Archaeology

Students on our MSc in Human Osteoarchaeology spend a lot of time looking at bones, funnily enough. But recently, they got the chance to make them… in felt. Why? We’re glad you asked! Felting is an ancient technique which, traditionally, created a textile by matting together wool using only heat, moisture and agitation. Examples of […]

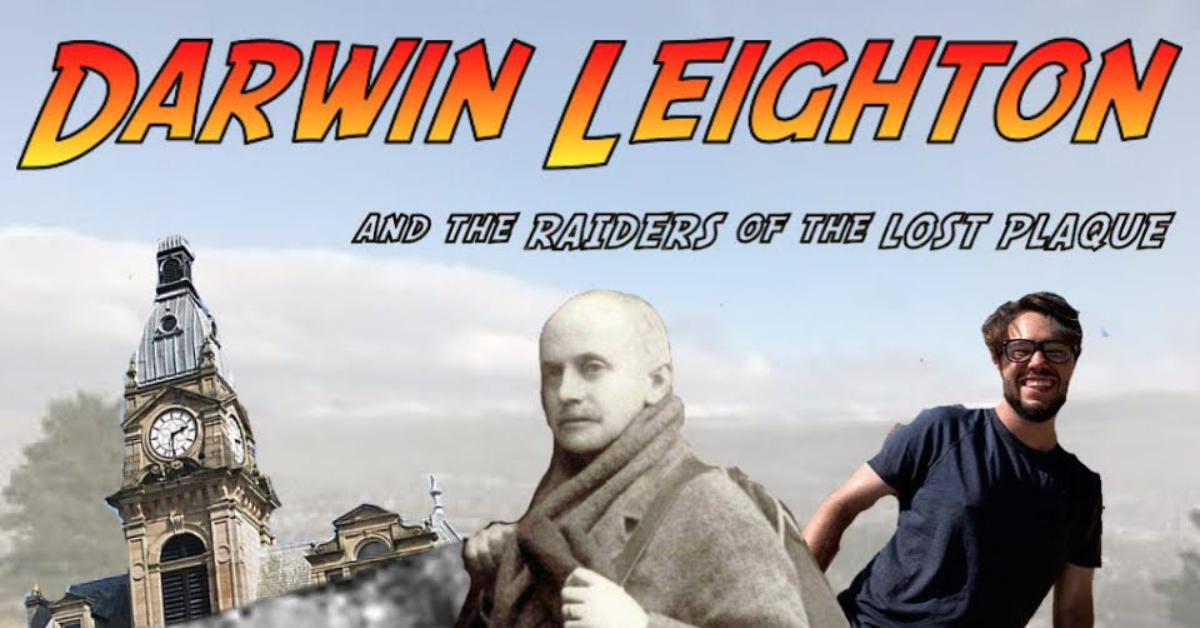

Dr Henry (Indiana) Jones Jr once said, “If you wanna be a good archaeologist you gotta get out of the library!”, which is exactly what some of our first year archaeology students did recently. The School of History, Classics and Archaeology is lucky enough to have a wealth of archaeological sites on its doorstep. A […]

In this blog post, Tessa Warinner, wellbeing adviser at the School of History, Classics, and Archaeology, discusses ‘Burnout’ – a rising concern in academia. Tessa discusses what it feels like, its prevalence, impact, and signposts helpful resources for managing it. This post belongs to the Hot Topic theme: Critical insights into contemporary issues in Higher Education. I’m […]

In this post, Rose Day, Learning Technologist at the School of History, Classics, and Archaeology (HCA), highlights the HCA TEL Learn Ultra Showcase. The showcase features some of the innovative courses and provides insightful commentary from course organizers and learning technologists who played pivotal roles in their development. This post also belongs to the Spotlight on Learn […]

Tanvi shares her experience of being an international student, and the supportive community of School of History, Classics and Archaeology. Student life in Edinburgh is colourful and multifaceted, and this is something that the University has continued to provide throughout my time as a student here. My experience at the School of History, Classics and Archaeology […]

Before Indiana Jones, there was Vere Gordon Childe. The great man – Indiana Jones – recommends him to his students as he skids across a library on the back of a motorbike, but not even he had access to the Vere Gordon Childe Teaching Collection. The Vere Gordon Childe Teaching Collection is a unique collection. […]

When History and Archaeology student Tom’s outreach project fell foul of Covid, he looked closer to home for inspiration and Footnotes was born. One day in December I was trawling through reports written by the commercial archaeology firm Oxford Archaeology North about the archaeology that they had found in my local area. Commercial archaeologists survey […]