Distant with Nature

As a kid growing up in developing countries, where the government focused on development, and raised by a family that was bombarded by media, nature is hostile; for instance, we have periodic flooding, earthquakes, landslides, volcanic activities, you name it. I found myself as a stranger to nature. Green Open Space (GOS), which is expected to be the closest natural environment for individuals to interact with nature, doesn’t seem to exist to its potential. Jakarta’s GOS has significantly decreased in less than two decades, the degradation could be seen from the total GOS recorded between 1982, 2000, and 2013 which accounted for 40%, 20%, and 13% consecutively. Regulation of the Minister of Public Works of the Republic of Indonesia Number 5 of 2008 requires a minimum percentage of green open space provision in urban areas of 30%, consisting of 20% public green open space and 10% private green open space.

Figure 1. Degradation of GOS Landcover in DKI Jakarta between 1982, 2000, 2013 (source: https://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/jli/article/view/14074/10509)

Mass urbanisation and the significant increase in population have destroyed watersheds and urban greenery to build housing, shopping malls, and business centres. Land use changes like this cause groundwater absorbent & albedo removal, and trees that produce O2 and absorb CO2 disappear, not forgetting the extra weight that we put into accommodating new activities. Cities’ sustainability and regeneration strategies mainly focus on man-made and built components of the urban environment (Chiesura, 2004).

GOS acts as the lung of a city, not just because they produce oxygen & absorb carbon dioxide, but they also absorb pollution (air, water, land), manage groundwater & erosion, natural habitat for animals, research opportunities, improve city landscape, recreational, restricted nursery resources, and others. Other studies also prove that GOS benefits social and psychology that are important in increasing urban life quality. Despite the benefits mentioned above, the reality of coexisting with nature isn’t perceived to have direct & tangible economic values (which unfortunately still the main drive in Indonesia’s infrastructure).

Healing trend: the nurturing nature

There is a trend among the ‘Jakartans’, where the young professionals need to escape from their daily lives by hiding in nature (e.g., camping, on a remote island, living on board, etc.). This trend is justified by a paper written by Sudimac, S., Sale, V., and Kuhn, S. (2022) justified, even though urbanisation has many advantages, living in a city is a well-known risk factor for mental health. Mental health problems like anxiety, mood disorders, major depression, and schizophrenia are up to 56% more common in urban compared to rural environments. Given exposure to nature provides attentional restoration and stress relief known as:

- Attention Restoration Theory (ART)

Attention Restoration Theory (ART) (Kaplan, 1989, 1995) suggests that mental fatigue and concentration can be improved by time spent in, or looking at nature.

- Stress Recovery Theory (SRT)

Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) defined as the restorative process is related to the stress-reducing capacity of natural environments that involves an increase in positive emotions as well as a decrease in arousal and negative emotions such as fear.

The study further compared restorativeness and enjoyment perceived between nature walk to urban walk, which result as predicted where nature walk scored higher. Researchers also revealed the mechanism behind the long-term effects of the environment on stress-related brain regions. Leaving us with the responsibility of modifying current and future cities to provide accessible green spaces to improve citizens’ mental health.

Children can benefit from nature too.

A team of researchers from McGill and Université de Montréal’s Observatoire pour l’éducation et la santé des enfants (OPES) found that spending two hours a week of class time in a natural environment can reduce emotional distress among 10 to 20 years old. Combining schooling activities in the park, for instance, regular classes and activities designed to promote mental health like drawing a tree or a mandala, writing haikus, mindful walking, and talking about cycles of life and death in nature. After three months, the teachers noted that the biggest changes in behaviour occurred in children with the most significant problems at the outset, including anxiety and depression, aggressivity and impulsivity, or social problems relating to interaction with their peers. The result suggested that children were more calm, relaxed and attentive in class after time spent in nature. “The intervention was low-cost, well-received and posed no risks, making it a promising strategy for schools with access to greenspaces” Tianna Loose, a post-doctoral fellow at Université de Montréal and the first author of the paper.

Urban Planning Case Study: Jakarta

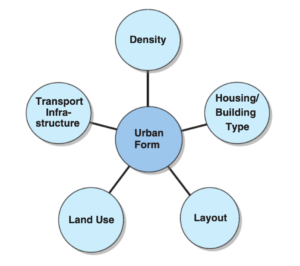

Figure 2. Urban form elements (source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226686462_Elements_of_Urban_Form)

Dempsey N., et al (2010) Chapter 2 Elements of Urban Form noted Urban Form generally encompasses several physical features and non-physical characteristics including size, shape, scale, density, land uses, building types, urban block layout and distribution of green space. These are categorized as five broad and inter-related elements that make up urban form in a given city. These elements of urban form have been identified on the basis that they are claimed to influence sustainability and human behaviour. However, this assumption might differ for developing countries’ urban form.

Measuring the subject’s satisfaction towards development is crucial, as it is for when we are building something that is not perceived positively by its subjects. Mulligan, Carruthers, and Cahill (2004) broadly interpret Quality of Life (QoL) as the satisfaction that a person receives from surrounding human and physical conditions. While Urban Quality of Life (UQoL) can be considered as the QoL in cities. Access to spatial resources, such as a good neighbourhood and district, green spaces, and rivers is an essential aspect of QoL in cities (Streimikiene, 2015). Given a dynamic result when scholars trying to find the correlation between urban form and UQoL in a developing country context, Komalawati, R. A., Lim, J. (2020) tried to unravel this question “Do dense and mixed-use areas tend to have a higher level of UQoL compared to other groups?”. They separated the research subjects into three groups:

- Group HH: respondents who live in superblock apartments (described as compact, dense, and mixed-use areas), denoted as High Density and High Mixed-Use (HH)

- Group HL: respondents who live in public housing apartments (described as compact and dense areas, but with single land use of residence), denoted as High Density and Low Mixed-Use (HL)

- Group LH: respondents who live in single detached-house residences (described as dispersed area, but mixed-use area), denoted as Low Density and High Mixed-Use (LH)

Figure 3. Urban quality of life variables/indicators of the study (source: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/12265934.2020.1803106)

LH > HH > HL

The result showed that residents who live in low-density and high mixed-use (LH) areas perceived comparatively better UQoL than residents living in high-density and high mixed-use (HH) or high-density and low mixed-use (HL). Mixed use plays a more important role in improving residents’ UQoL than does density.

Since the population is already dense and land plots are no longer available, how can we slow down this rapid change? Besides extreme socio-economic contrasts, traffic congestion, pollution & urban heat traps, the decline originally designated as catchment, & green open space is just history now. If we tie it back to the initial topic of significant relations between nature and mental health, according to research data from I-NAMHS in 2022 analysing Indonesian children mental health aged 10-17 years old, roughly 13 million teenagers have mental health problems, and 2 million have mental problems. This is rather a serious mental health issue for teenagers according to I-NAMHS. Another finding from this research was suicidal behaviours and self-harm non-suicidal behaviours over the past 12 months were reported by those with mental health problems teenagers. It’s probably worth noting that 58% of respondents reside in Java & Bali Island.

Reflection points

Figure 4. Serenity of morning activities taken in Mount Gede Pangrango National Park, West Java, Indonesia (source: https://pefc.org/news/winning-photos-show-the-magic-of-indonesias-forests )

In the context of devastating climate change where it affects anyone in many aspects, be it health, food security, or hostile habitat (not only humans but other living creatures). Indonesia used to be 80% tropical forest in the 1960s (RAN, no date), and it seems like only natural and low-cost to restore it. I’m not saying we should erase humanity and urbanisation, is there a win-win solution for us to accommodate nature-based and urbanisation in adaptation to climate change? Have we strategised the development in the right way? Or is Jakarta as a special purpose city setting a bad example of catastrophic development that we should prevent being adopted in other cities?

Leave a Reply