Keywords: Green open space, urban forest, ecology, health, Jakarta, Indonesia, challenges

According to UNFPA Indonesia (2015), the population of Indonesia living in urban areas has surpassed 50% and is expected to continue growing. UNFPA Indonesia (2015) also argued that the majority of the Indonesian population will not return to living in rural areas but rather in a range of urban settlements. Urbanisation and land use will have a direct impact on nature, biodiversity, and other factors. If not planned and controlled properly, urban development will not be sustainable and will overlook the benefits of nature for its inhabitants that ideally allow both to coexist.

Dogan, D., Bulut, M. B. B., Demirel, O. (2021) summarised publications that elaborate the multifaceted functions of city parks, namely from ecological, recreational, health, educational, socio-cultural, collective memory and place attachment, social equality, security, and land organisation perspectives. Aligned with the argument above, a study conducted by Cox, D.T.C., et al (2018) found that people who choose to spend more time in nature more often, and for longer, are healthier across multiple dimensions of health.

In reality, we still witness it today: water inundation in Jakarta [1], daytime poor air quality in several major cities in Indonesia [2], and others. This can be countered if there is an awareness to create a sustainable ecosystem by bringing nature closer to urban development through urban forests.

As defined by Cities4Forest (2019) “An urban forest encompasses the trees and shrubs in an urban area, including trees in yards, along streets and utility corridors, in protected areas, and in watersheds. This includes individual trees, street trees, green spaces with trees, and even the associated vegetation and the soil beneath the trees. In many regions, urban forests are the most extensive, functional, and visible form of green infrastructure in the city.”

Table 1. Different Types of Urban Forest by Cities4Forest

| Trees on private property

|

Trees on private (leased) land may be protected by law in some regions. |

| Street trees

|

Streets are, in turn, the most prominent type of publicly accessible urban landscape, and trees have long been understood as essential elements of streetscape design often associated with enhancing the experience of living in cities [3] |

| Streets with green infrastructure

|

Green street practices selecting green infrastructure elements, such as bioswales, rain gardens, and permeable pavement, that can be incorporated into a traditional street design to create a “Green Street”. Green street practices capture, retain, treat, and/or infiltrate stormwater runoff from impervious surfaces such as roadways, parking lots, sidewalks, and rooftops. [4] |

| Pocket parks

|

Studies suggests that small urban green spaces such as pocket parks less than 5000 m2 or other forms such as street trees, flower beds or green roofs within the urban context could offer recreational and experiential benefits (e.g. Peschardt et al., 2012; Danford et al., 2018; Mesimäki et al., 2019). [5]

Urban pocket parks refer to urban open spaces, that are small in size, low in expenditure, easy to access, and flexible in shape and location for more livable and comfortable urban areas. [6] |

| Urban Parks

|

Benton, L.M. (2024) Urban parks are designated green spaces within cities that serve recreational purposes and promote environmental awareness. Frederick Law Olmsted advocated urban parks as essential “lungs of the city,” emphasizing their role in enhancing public health and offering respite from the stresses of urban life.

Over the years, the focus of urban parks has shifted from mere pleasure grounds to multifunctional recreation facilities, incorporating diverse amenities like sports fields and playgrounds. |

| Linear Parks

|

An interconnected park typically along rivers, streams, or canals that are connected by pedestrian walkways and bicycle paths. It is a nature-rich and immersive outdoor experience that can offer an inspiring retreat from daily life and enhance personal identity and lifestyle by sparking interactions with nature and with others. [7] |

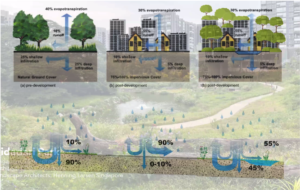

Figure 1. Comparison of green and grey infrastructure’s ability to absorb water. Source: Siura, A. (2025)

The figure above was presented by Anton Siura, a regenerative landscape architect at Eco-Mantra 2025 Webinar: Embracing Regenerative Design on June 26th, 2025. A design that is still far from the reality of development in Jakarta and major cities in Indonesia. The image above conveys development that combines grey and green infrastructure. Where the larger the composition of green infrastructure, the more optimal soil absorption, hence the lower the potential for stormwater runoff.

Nonetheless, as we know trees won’t just grow overnight. Urban Forest requires long-term planning, interdisciplinary professional coordination, and local participation. To secure the ever-growing health and vitality of urban forests, which benefits urban dwellers (FAO, 1998). Some other urban forest challenges identified, such as:

- Green infrastructure requires careful installation and plans for long-term maintenance. [8]

- Regular care (the right policies, plans, regulations, and institutional arrangements can help to sustain healthy urban forests and deliver important benefits to people) [9].

- Land ownership and urban forest zoning limitations. Where zoning aims to create, expand, or maintain urban forests.

- Often economically undervalued, especially in low- or middle-income countries with many urgent planning priorities. [10]

Leave a Reply