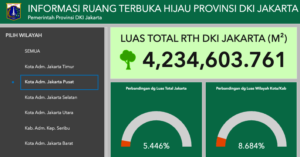

Figure 1. Interactive data of green open space (RTH) areas in DKI Jakarta. Source: Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta (accessed on August 15, 2025)

According to data from the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta, the area of green open space in DKI Jakarta is equivalent to 5.4% in line with the article by Prakoso, P., Herdiansyah, H. (2019) which is far below the target of Law Number 26 of 2007, which is 30% of the administrative area. As a matter of fact, the current total area has decreased to 36.03 km2 compared to the article citing Novianty, Neolaka, & Rahmayanti (2012), which was 59.25 km2. Currently, Central Jakarta is the municipality with the largest green open space area, namely 4.2 km2 (8.68%).

My previous blogs, “Urban Forest Benefits and Challenges” and “Urbanisation vs. Nature: The Battle for Green Spaces in Jakarta” highlighted the urgencies and benefits of green open space (RTH) in urban areas, especially Jakarta, Indonesia. UNFPA Indonesia (2015) predicts that the population of Indonesia living in urban areas has surpassed 50% and is expected to continue growing. This monograph also argued that the majority of the Indonesian population will not return to living in rural areas but rather in a range of urban settlements. Will all areas be developed without regard for ecology and biodiversity, as is currently happening in Jakarta?

According to Prakoso, P., Herdiansyah, H. (2019), the problems with fulfilling green open space in DKI Jakarta consist of:

- Technical aspects related to land conversion are based on the Jakarta government’s lack of control over land use allocation in DKI Jakarta Province.

- Economic aspect of land acquisition, research by Subarudi & Samsoedin (2012) indicates that to fulfil the 30% green open space (RTH) target, the Jakarta government needs to acquire 13,748.12 hectares of land, costing Rp 13.748 trillion.

- Policy and political aspects include green development policies that receive full and consistent attention and support from political parties.

To address the above issues, Prakoso, P., Herdiansyah, H. (2019) offer the following solutions:

- Improve regulations to facilitate the addition of green open space.

- Incorporate policies for expanding or fulfilling green open space in Jakarta into the Jakarta Long-Term Development Plan (RPJP).

- Make environmental aspects the basis for providing and managing green open space, such as the principles of sustainability, continuity, harmony and balance, and other principles.

- Promote public-private partnership (PKBU) schemes to develop and meet green open space targets.

- Optimise existing land and gradually engage with community participation, such as in areas along rivers, waterways, lake and reservoir boundaries, along coastlines, along toll roads, along railway lines, and areas under high-voltage overhead lines.

- The community plays a role in optimising the surrounding land for green open space development. Community participation can be carried out to reduce the costs of creating and releasing land for green open space, through the financing mechanism carried out by the DKI Jakarta Regional Government. It is hoped that there will be cooperation with the community and entrepreneurs to allocate green open space in their respective areas.

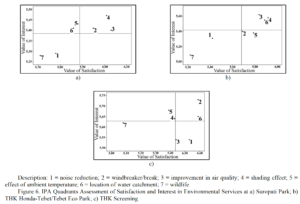

Oktavia, R.C.D. et al. (2023) analysed the environmental satisfaction and interest of visitors and residents around green open spaces. This research sampled urban parks and urban forest parks in three different locations in Jakarta: Penjaringan Urban Forest Park (North Jakarta), Suropati Urban Park (Central Jakarta), and Tebet Eco-Park Urban Forest Park (South Jakarta). The table below shows very interesting results, indicating that visitors are aware of the importance of environmental services provided by Urban Parks (TK) and Urban Forest Parks (THK), represented by noise reduction, windbreaks, air quality, shade effect, micro-temperature effect, water catchment location, and wildlife habitat. In terms of visitor satisfaction with environmental services, Tebet Eco-Park and Suropati TK scored higher than Penjaringan THK. Certainly, location, facilities, management, and other factors play a significant role in visitor satisfaction.

Table 1. Assessment of Visitor Satisfaction and Interest in Environmental Services Provided by Urban Parks and Urban Forest Parks

Source: https://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/konservasi/article/view/46628

Researchers also conducted an assessment using a Cartesian diagram to determine which aspects needed to be maintained (quadrant 1), prioritised as high priority (quadrant 2), low priority (quadrant 3), and excessive (quadrant 4). Once again, the geography of the green open space area certainly plays a significant role in determining priority levels and visitor needs. However, it’s interesting that across all three results, the wildlife indicator consistently ranked as a low priority compared to the other indicators.

Figure 2. Cartesian diagram result to categorise visitors’ satisfaction and interest in environmental services provided by urban parks and urban forest parks. Source: https://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/konservasi/article/view/46628

Figure 3. (A) Comparison of green open space area percentage between Singapore and Jakarta between 1985 and 2020 (B) Singapore population growth (C) Jakarta population growth (D) Singapore GDP per capita trend from year to year

Source: (A) https://jpi.or.id/en/graphics/city-stats-green-open-space/ (B) https://data.who.int/countries/702 (C) https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/indonesia/jakarta (D) https://id.tradingeconomics.com/singapore/gdp-per-capita

To meet the green open space target, ensuring that urban development can be integrated with the provision and maintenance of green open space and green buildings, Indonesia needs to learn from its neighbour, Singapore. The figure above shows that Singapore has successfully increased and maintained its green open space over time, despite its population and economic growth.

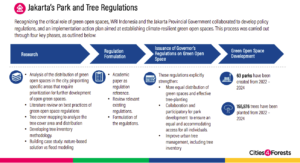

According to JPI, in DKI Jakarta, one government agency is responsible for carrying out the green open space management function, namely the DKI Jakarta Provincial Parks and Urban Forestry Agency. On the other hand, there is an initiative from the World Resources Institute (WRI) Indonesia called Cities4Forest, in collaboration with the DKI Jakarta Provincial Government, to encourage the use of nature-based solutions (NbS) in a number of programs since 2019. The image below explains the support and framework of Cities4Forest, specifically for DKI Jakarta Province.

Figure 4. Cities4Forest‘s scope of support and framework for DKI Jakarta Province. Source: Tjokorda Nirarta Samadhi (2025) presentation at Eco-Mantra 2025 Webinar: Embracing Regenerative Design on June 26th, 2025

Leave a Reply