Keywords: waste management in Bali, preferences, challenges, improvements, behaviour, communication, education, campaign

———————————————————————————-

The issue of waste in Indonesia remains a shared problem that has yet to be resolved. Since the issuance of Presidential Regulation No. 97 of 2017, which regulates the National Policy and Strategy for Household Waste and Similar Household Waste Management (Jakstranas), is expected to be completed by 2025. Nonetheless, according to the Waste4Change (2025) webinar, the achievements are still far from the targets: waste reduction is only 19.7% (target 30%); while waste management achievement is 50.1% (target 70%).

If we take the example of Bali Province where the Author resides, according to (SIPSN, 2024), around 593,234 tons of waste were left unmanaged annually (24.13% of the total waste generated in 2023). Unmanaged waste ends up being burned, openly dumped on the roadside, or disposed of in water bodies.

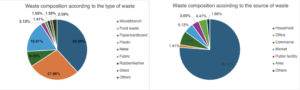

Figure 1. Bali waste composition according to the type and source. Source: National Waste Management Information System (SIPSN, 2024)

To provide an overview of the waste context in Bali, Figure 1 left illustrates the waste composition and sources in Bali Province. Where wood/branches (38.2%) dominated the waste composition, followed by food waste (21.66%) and plastics (16.91%). Meanwhile, Figure 1 right depicts the sources or origins of the waste. Where the largest contributions come from households, markets, retail, grocery, restaurants, hotels, and accommodation (SIPSN, 2024).

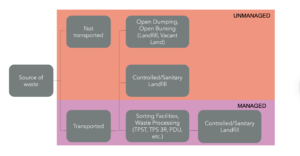

Figure 2. Waste flow scheme in Indonesia. Source: interpretation from Waste4Change webinar.

On June 25, 2025, the Author attended a webinar organized by Waste4Change titled “Financing Fair and Sustainable Waste Management.” One of the speakers, Anissa Ratna Putri, Head of Consultant Ecosystem at Waste4Change described the waste flow scheme in Indonesia, including the province of Bali, is represented by the image below. Where waste is categorized into two categories: managed or unmanaged. What is included in managed waste is waste that is collected and then enters waste sorting and processing facilities (such as TPS3R, TPST, PDU), before proceeding to Controlled/Sanitary Landfill. On the other hand, unmanaged waste is waste that is not collected. However, waste that is collected but does not go through the sorting and processing facilities, but is instead directly taken to Open Dumping, Open Burning (such as in landfills and vacant lots), or Sanitary/Controlled Landfill can also be considered unmanaged waste.

She conveyed that in achieving the Jakstranas target, which is part of the RPJMN 2025-2029 aiming for 100% waste management by the end of the period, there are many challenges to be faced, including leaks, reinforcement, funding sources for facilities (such as transport trucks), and dependence on landfills. To address this, the speaker mentioned that we do not lack technical options, but the crucial points here are the aspects of Governance, Partnership, and Financing. Because the allocation of the regional budget (APBD) cannot cover the entire cost of waste management services, there is a gap that must be filled through waste disposal fees, which can vary by region. Based on the same logic, the higher the waste generation, the higher the financing needed (including waste collection fees). Therefore, efforts to reduce waste generation have become the main focus of this blog.

The author wants to share a case study of the Kopernik experiment, where researchers aim to test the Incentive and Sanction System to Promote Waste Sorting Behavior using the “Nudge Theory” and “Prospect Theory” approaches.

Nudge theory was popularized by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein through their book titled “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness”. Nudge theory aims to change people’s behavior without having to restrict their choices. An important feature of nudge theory is that the intervention to change the behavior should be easy and cheap to avoid by people – thus not putting any economic constraint on them (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). On the other hand, Prospect Theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979 (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) to explain why people tend to avoid losing something. Prospect theory states that humans, in general, tend to experience greater pain from losing an amount (of money) as compared to the pleasure experienced from gaining the very same amount. Meaning, that the pain experienced by losing IDR 10,000 is greater than the pleasure of gaining IDR 10,000.

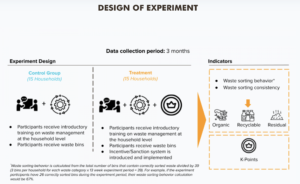

Figure 3. Kopernik’s approach for the research

Results:

- The treatment group had a slightly higher average sorting rate and sorted waste more consistently. Though statistically, this is not a significant result.

- When we compared the sorted waste based on the waste categories, the treatment group performed more consistently in sorting residual and recyclable waste. On the other hand, the control group performed better in sorting organic waste. The average waste sorting behavior in all waste categories across groups was very high.

- The treatment group had slightly higher average K-points at the end of the experiment (39.07) compared to the control group (38.32). This result shows that both the control and treatment groups performed well in terms of waste sorting behavior during the experiment.

- There was a sharp decrease in waste sorting performance across both groups. This was likely caused by a series of religious ceremonies that increased the volume of waste in general, which resulted in more sorting errors.

Another research Author found was conducted by Suryawan, I.W.K, et al (2025) on Hypothetical scenarios for circular bioeconomy preferences in the Bali metropolitan area. Using three different scenarios to examine residents’ attitudes towards different waste management practices. Scenario 1 focused on collecting and separating waste to support existing infrastructure, Scenario 2 emphasised source reduction and participation, and Scenario 3 integrated into a comprehensive circular economy approach. The study reveals significant support for comprehensive waste management practices, with high marginal willingness to participate values for initiatives such as collecting and processing paper waste for energy conversion, independent composting of food waste, and community-based composting of garden waste. These findings highlight the importance of community engagement and tailored strategies in developing sustainable waste management programs. The results provide valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders to design effective circular bioeconomy policies that enhance local economic self-sufficiency and contribute to sustainable development goals.

Leave a Reply