Week 14: Curatorial Text

Introduction

In this blog post I focus on presentational curatorial texts.

As I started to consider curatorial texts, I decided to complete an analysis of two institutional guides intended to serve as manuals on how to complete exhibition texts, followed by an analysis of four case studies.

The following considerations are based on guides published by the V&A and the Smithsonian Museum, which I will discuss from the position of my own personal speculative project. Though these are not contemporary art galleries, they are public institutions and thus have been subject to the same cultural shift towards audience engagement within the educational turn. They pose valuable perspectives on considering how an audience will engage with an exhibition and the text that accompanies it.

Identifying public

Writing should be completed with a specific public in mind.

With a goal that attempts to contextualise the individual in a collective network, exiled publics would conceptually harm my speculative project. Climate change is an issue that befalls publics beyond societal subdivisions; many groups will find meaning in the exhibition. Further, as climate change has been established as a collective issue, in turn, restoration is only possible through collaborative efforts. Thus, as many people as possible will be engaged. The featured artists are also graduates, so I should not intentionally limit the number of people who can participate in the exhibition when artist exposure is valuable at this career level.

My public will be based on the Getty Museum’s hypothetical individual, the ‘Art Novice’, based on the premise of creating an imaginary figure that presents requirements that, if met, would allow for a universal comprehension:

• Is curious and motivated to learn

• Spends less than 30 seconds looking at an object

• Has underdeveloped perceptual skills

• Is unfamiliar with art terminology

• Expects a quick pay off (‘art should grab me’)

• Senses that their knowledge is limited and limiting to their enjoyment

• Lacks confidence in their ability to make sense of what they see

• Makes emotional and personal associations with the object first

• Wants to connect with the people associated with the object

I believe these qualities align with my established audience, and by keeping this archetype in mind, I think that I will be able to complete a form of writing that best communicates the exhibition to a universal viewer.

Content pathways

Within all subsections of publics and societal groups, people will engage with curatorial texts in different ways. Some will scan the writing, while others will have focused engagement, preferring more details. The Smithsonian guide suggests that both of these preferences can be catered to within one piece of text. By establishing key information at the beginning of paragraphs, readers who only offer the text a cursory glance will be able to get an impression of the curatorial themes. Additionally, as the viewers are estimated to spend only 30 seconds looking at a piece of art or writing before deciding if it is deserving of more attention, a hierarchy of importance will be developed so that the most relevant information is first.

Bringing in the human

There is a disconnect between the viewer and the art object; additionally, the ‘art novice is one who makes connections based on their own personal associations’. Presenting themes through examples and sensory experiences will embrace the tendency to conceptualise an exhibition in a self-referential and object-orientated way. A descriptive material-led text will communicate themes better than a concept-led abstract presentation.

Content

The audience does not need to be told everything. There is a balance between giving enough information to enjoy the exhibition, overwhelming the viewer, and embracing an indeterminacy in the subject that creates a sense of curiosity (a component of the ‘art nouveau’ that should be embraced). Additionally, the tone should be developed in a way that suits the public and complements the curatorial theme. Passive sentences should be avoided, as they make the writing feel academic and esoteric.

Case study analysis

Titles

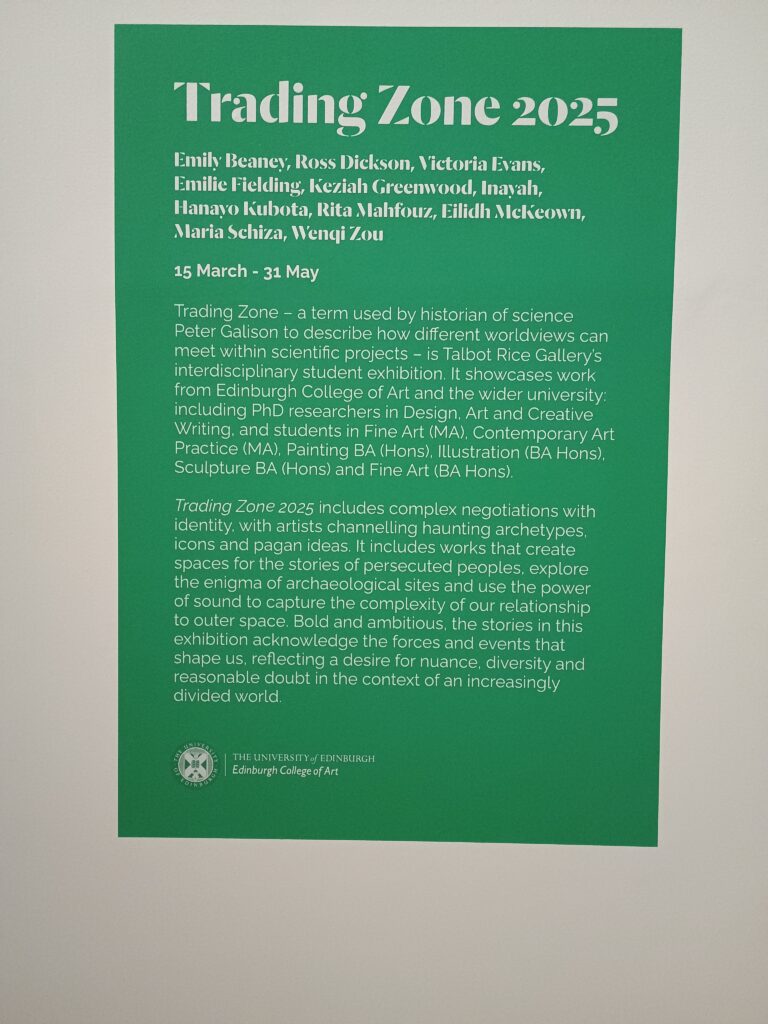

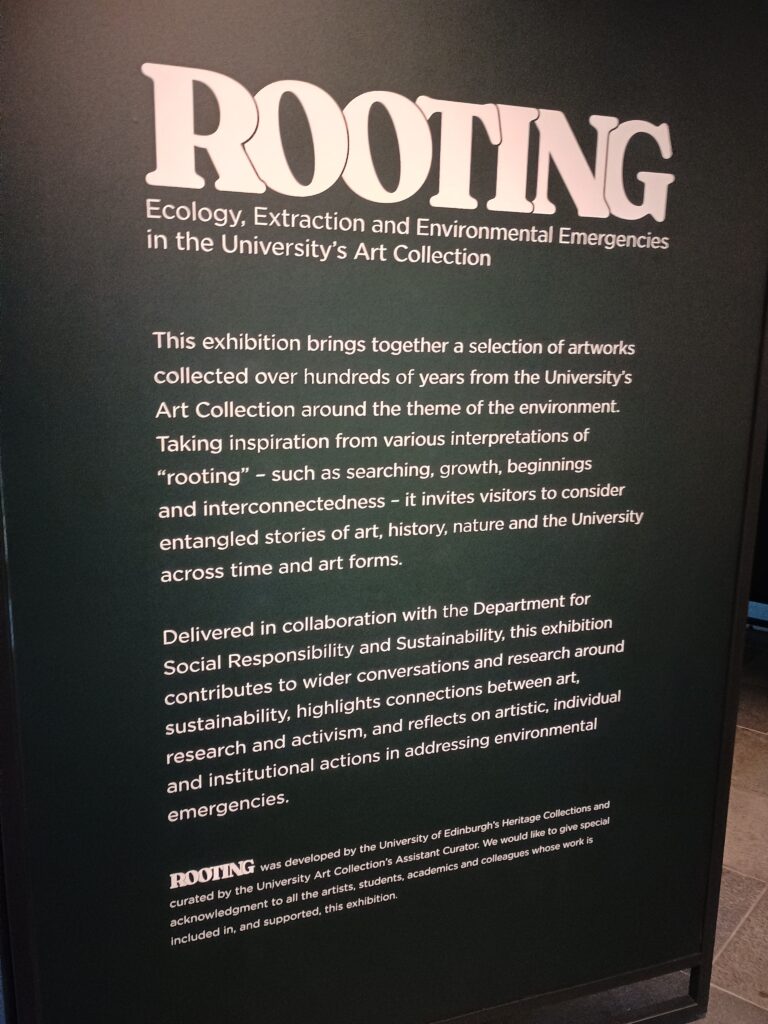

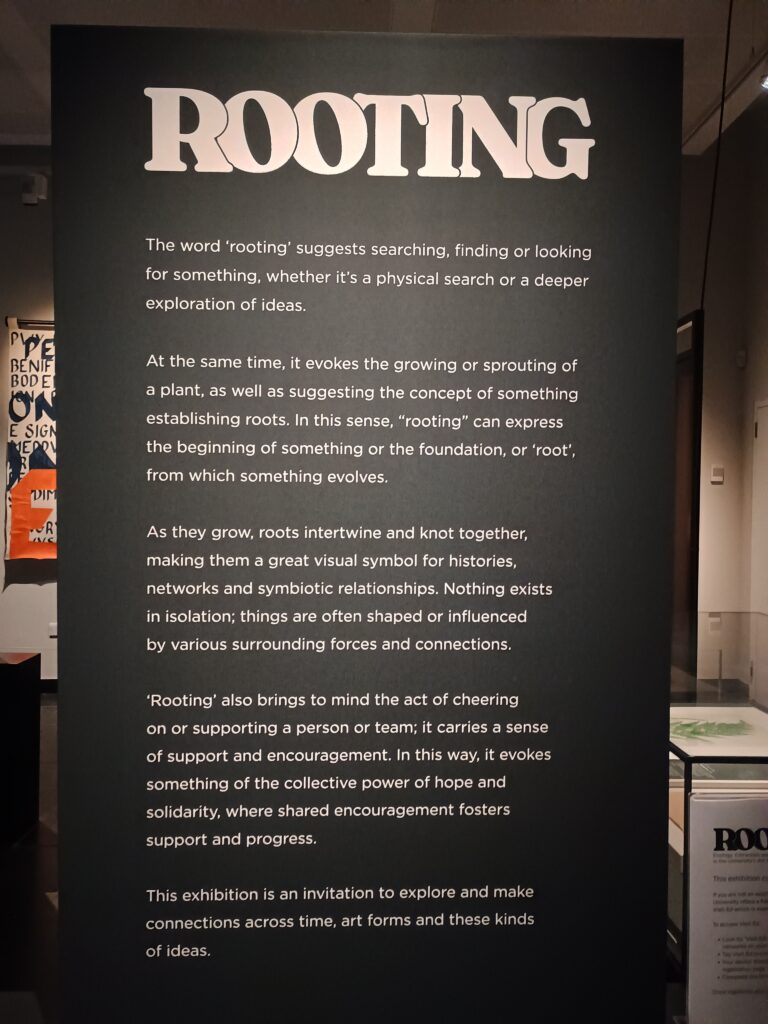

Both the Talbot Rice Trading Zone and Edinburgh Library’s Rooting start their gallery texts with a description of their title. In the case of Trading Zone, this was necessary for two purposes. First Trading Zone was a specific reference to a theorist. The introduction served to cite this thinker and justify the use of it as a title that may have otherwise seemed unfounded. Second, as I wrote in my curatorial analysis of Trading Zone; the framing that the title and wall text provided enabled the exhibition to move away from the narrative/thematic curation that is typical for contemporary exhibitions. On the other hand, Rooting discussed the title as it used the word as a homonym, referring both to the roots of plants and also to the process of building a foundation of knowledge. The title becomes an area of interest because of its linguistic purposes; as a result, it is used to frame the rest of the exhibition text.

Trading Zone Exhibition Text (2025), Talbot Rice Gallery, Photographed by Harry Mayston

Rooting Exhibition Text (2025), Edinburgh University Library, Photographed by Harry Mayston

Rooting Exhibition Text 2 (2025), Edinburgh University Library, Photographed by Harry Mayston

Exhibition goals:

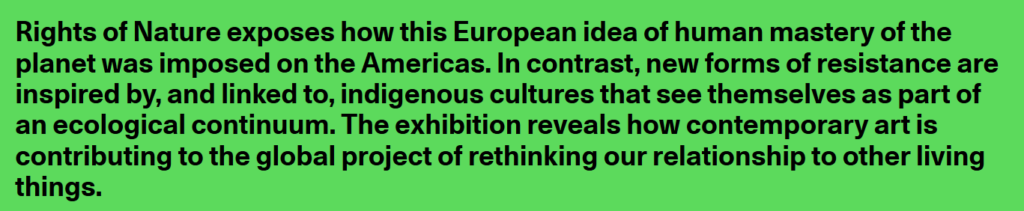

The goal of the exhibition is stated at the end of curatorial texts.

For these socially engaged ecological exhibitions, the exhibition goal provides a lens from which to view the exhibition as the viewer anticipates the result. By ending the text with the goal, it acts as a conclusion for the text but also suggests that it is a conclusion we should reach at the end of the exhibition.

Rights of Nature (2013), Nottingham Contemporary, Screen Capture sourced from:https://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/whats-on/rights-of-nature/

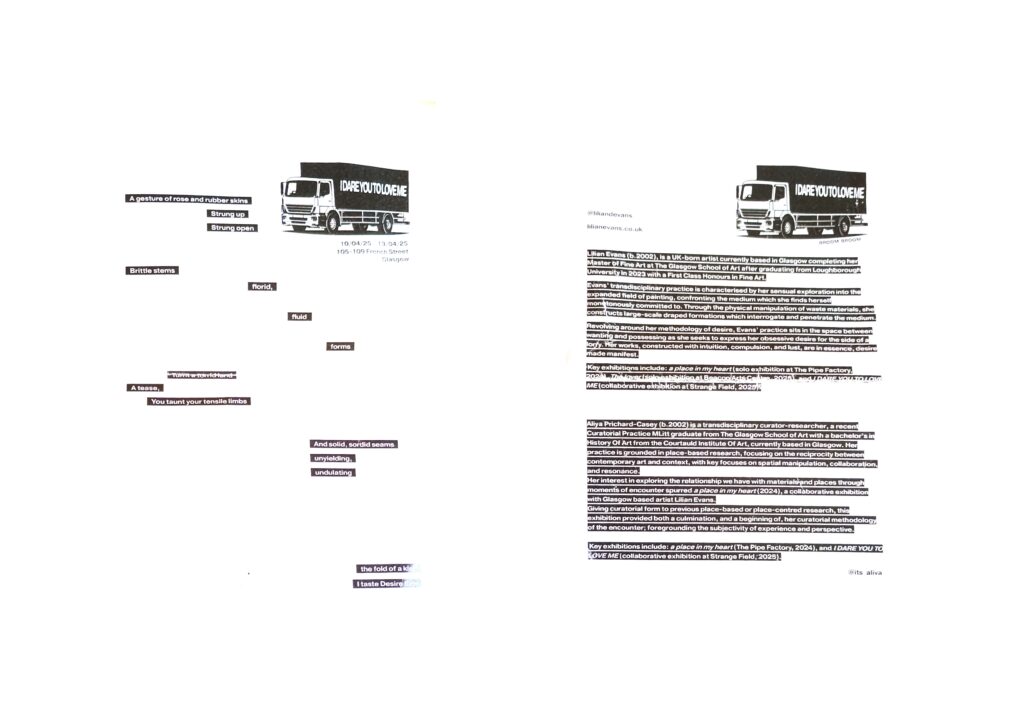

Exhibition Voice

In the I Dare You to Love Me Exhibition, the curatorial text comprised two parts. The first is poetic, iterating the writing that is displayed in the exhibition. It is a purely thematic piece that does nothing to explain the exhibition. It acts as an extension of the exhibition, as an experimental form of exhibition voice that abandons convention in contributing to the tone of the exhibition. Alongside a change in graphic layout, the second piece of writing is more conventional for a solo exhibition, discussing the work of the artist as well as providing a small biography. The change in layout signifies the change in tone.

Evans, L. and Prichard-Casey, A., I Dare You To Love Me Curatorial text (2025), Strange Field Gallery, Photographed by Harry Mayston

Application to individual speculative project

Like the Talbot Rice Gallery and Rooting, I believe that the focus on the etymology of ‘weird’ and the manifold meanings that it inherits through the focus on historic definitions, as a result, require explanation.

The exhibition goal will be incorporated at the end of the text. Like Rooting and Rights of Nature, the socially engaged exhibition benefits from the clear statement of how the audience should anticipate the exhibition. With themes of ecology that the ‘art novice’ viewer’ will be unlikely to be educated on, a direct approach will be best. Alongside the position at the end of the text acting as a conclusion, it means that the curatorial writing will start with the title and theme and end with the exhibition goal; thus, even the skim reader will be able to gain an impression of the most vital parts of information.

Lastly, I liked the idea of having a 2-part exhibition text. One part that forms a more experimental section, acting as an embodiment of the curatorial message, rather than a description. This may take on the form of a creative or descriptive piece of writing. A creative format would be able to make material/example-based references that would make the curatorial themes more accessible to the viewer who benefits from object- and self-referential writing. The second section would be more detail-orientated and take on the more conventional form of curatorial texts. The tone will be distinguished through graphic design choices, using specific fonts to signify creative tonal writing and a traditional sans serif font to solidify the informational standard components of the text.

Bibliography

- Evans, L (2025). lilian evans. [online] lilian evans. Available at: https://lilianevans.co.uk/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2025].

- Nottingham Contemporary (2013.). Rights of Nature. [online] Available at: https://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/whats-on/rights-of-nature/. [Accessed 23 Apr. 2025].

- Talbot Rice Gallery (2025). Trading Zone 2025 | Talbot Rice Gallery. [online] Available at: https://www.trg.ed.ac.uk/exhibition/trading-zone-2025. [Accessed 23 Apr. 2025].

- The Smithsonian Institute (2015). The Smithsonian Institution’s Guide to Interpretive Writing for Exhibitions.

- Talbot Rice Gallery (2025). Trading Zone 2025 | Talbot Rice Gallery. [online] Available at: https://www.trg.ed.ac.uk/exhibition/trading-zone-2025. [Accessed 23 Apr. 2025].

- The University of Edinburgh. (2024). Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions. [online] Available at: https://library.ed.ac.uk/heritage-collections/museums-and-galleries/exhibitions-whats-on. [Accessed 23 Apr. 2025].

- V&A (2013). Gallery Text at the V&A: a Ten Point Guide.