Theme Development: Themes and Ethical Coniserations.

Introduction

During my week 5 individual tutorial, we discussed the need to refine the thematic and conceptual framework of my speculative project. Ecology as a framework is unique in the way that it has resisted aesthetic, medium, and ambition homogenisation. Instead, there is great variety in the ways that artists, and academics alike have communicated their unique messages, spanning disciplines from the philosophical (Bennet, 2015), and scientific (Simmard, 2021), to the poetic (Farrier, 2019), and indigenous (Kimmerer, 2013).

Mapping Themes

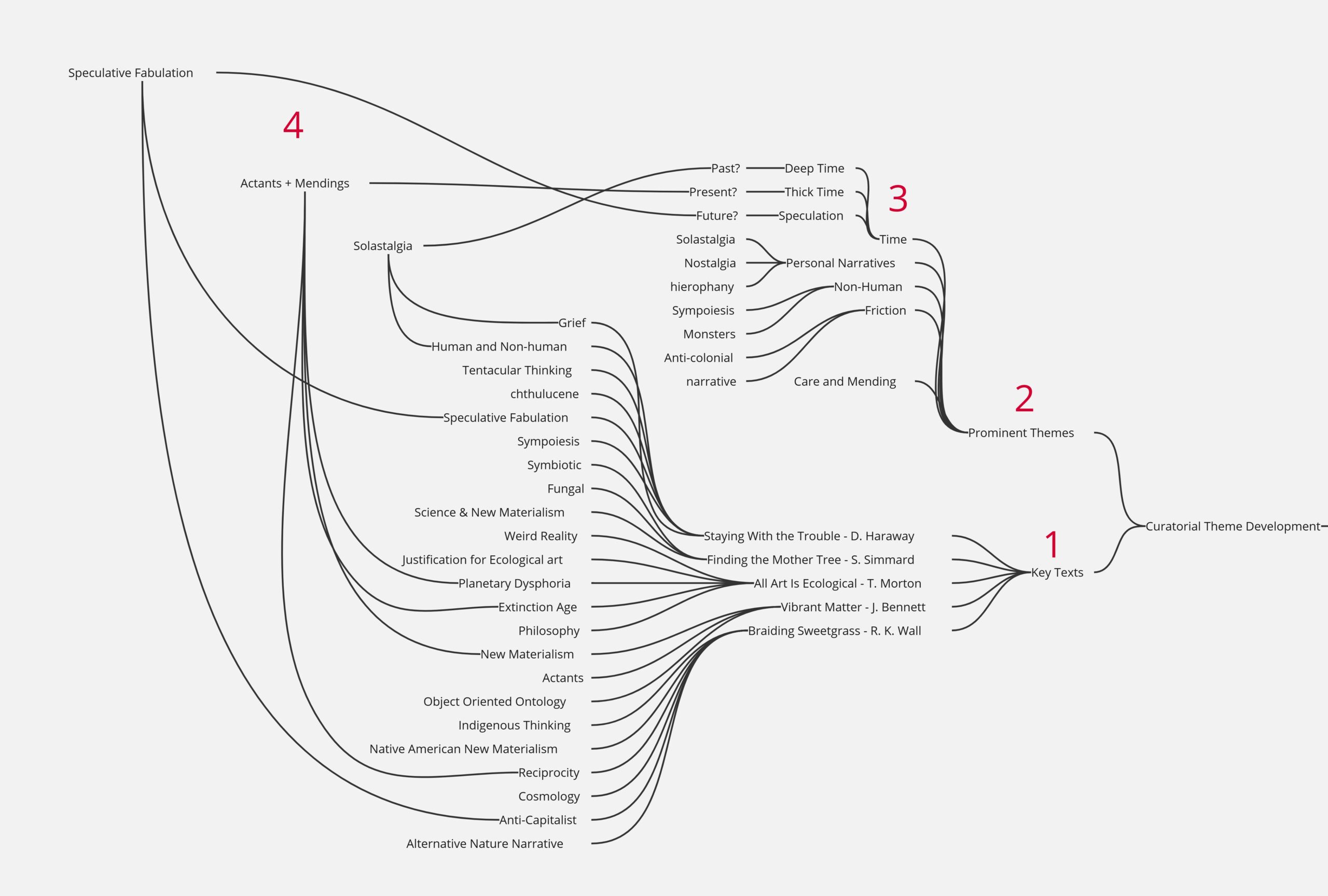

Inspired by James Kleggs curatorial diagrams presented in Week 4 I decided to imitate his process and map out curatorial influences

- To make sense of this noise I selected 5 texts that I believe span inclusively (but not comprehensively) across the subject of ecology and climate change. Seen below, I have plotted a diagram, identifying the key themes that are raised within each perspective.

- Then drawing on my own experiences of ecological art, as well as wider reading, I plotted further key themes that I believe are prominent to contemporary ecological arts discourse.

- From here I expanded my terms into subsections of more specific terms.

- Using both these branches of my diagram I was able to connect sections to examine the ways that these theories and contrasting viewpoints can work in harmony.

Action:

The diversity of artistic manifestations of ecology and climate is one that resists conceptualisation at first, however, as originally brought forth by Timothy Morton, the experience of strangeness is a symptom of living in, and with, the current state of ecology and crisis. Additionally, this confusing reality within practice does not need to be an antagonistic one, instead, as Nathan Snaza explains “before there is cognition there is an exposure to a set of relations that disorients, and in disorientating sets part of self into motion” (in Carstens, 2020, p.77). This concept echoes Anna Tsing’s term ‘Friction’ (2015) iterating the way that contrasting narratives lead to an advanced understanding of our own actions with a focus on how we progress into the future, ‘friction causes heat’ (Haraway, 2012)(Tammi, et al., 2024). In taking an anti-climate change, and anti-colonial (as discussed in previous blogs) position with this exhibition, the inclusion of a variety of narratives, and perhaps, contrasting ideological visions is necessary to instil this speculative project with a mobilising potency.

Starting from this point I can identify the necessary elements of my speculative project’s narrative that can be fulfilled by artists and artworks. Firstly, I noticed that within ecological theory there is an emphasis on time. Originally applied by John McPhee, the term ‘deep time’ is used to refer to the expansive scale existence of non-human, in comparison to anthropocentric notions of time (1981). In Contemporary Art this has been incarnated with the use of ancient materials, creating an intimate connection with the deep past. Secondly there is also a movement to imagine the future. Haraway uses the term ‘Speculative Fabulation’ (Carstens, 2023). The aim of these pieces is to make the audience imagine what they do and don’t want the future to look like, and then take action to realise this (Pierce, 2016, p. vii- x, in Gogh, and Morris, 2020, p. 11). These art pieces can take the form of either hopeful or apocalyptic future imaginings of a world in the future where humanity has either survived through compromise, and the form of tentacular thinking that is encapsulated by the Chthulucene, or an apocalyptic desolation of nature. Finally, the third form of art is that which is firmly planted in the present, focusing on the way that we interact with ecology in contemporary society, as well as weaving together past and future narratives through a possibility driven present.

Ethics:

The term ‘Anthropocene’ arises in conjunction with the themes of ecology and climate change. However, this name, though widely used, is contested. The literal meaning translates to ‘Era of Human’. The issue arises when this term becomes associated with the climate crisis, and as such, indiscriminately extends the blame of ecological harm to the entirety of humanity. However, this is a western viewpoint that does not acknowledge that the structures that have led to the dominant geological changes being caused by some humans, are the same as the ones that have subjugated bodies, cultures, and indigenous wisdoms. This has resulted in alternate naming suggestions to are current epoch, such as ‘Capitaloscene’ and ‘Plantationoscene’, drawing attention to the role of capitalism, and the plantation, respectively, in acting forces on the climate (Morton, 2018). To accurately represent the issues associated with ecology I will need to include artists that bring an anti-colonial objective, as well as ideas that relate to marginalised groups that may struggle to find institutional representation.

Bibliography:

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things.

- Carstens, D. and Gray, C. (2023). Doing Academia Differently: Taking Care of Humans, Technologies and Environments in the Digital Age. 7(1), pp.8–26

- Demos, T. (2013). Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology. Third Text, [online] 27(1), pp.1–9. [Accessed 18 Nov. 2024].

- Farrier, D. (2019). Anthropocene Poetics. U of Minnesota Press.

- Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Kimmerer R. W. (2003). Gathering Moss: a natural and cultural history of mosses. Corvallis, Or: Oregon State University Press.

- Kimmerer, R.W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, pp.205–215.

- McPhee, J. (1981). Basin and Range. Macmillan.

- Morris, A. and Gough, N. (2020). Post-Anthropocene imaginings: Speculative thought, diffractive play and Women on the Edge of Time. In: B. R, ed., Post-Qualitative Research and Innovative Methodologies. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic, pp.172–186.

- Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World

- Morton, T. (2018). Being Ecological. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press.

- Tammi, T., Riikka Hohti and Saari, M. (2024). Imagination switch – Friction and thick time in speculative worldmaking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, pp.1–14.

- Tsing, A (2015). Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton: Princeton University Press.