Project Background and Curatorial Motivation

what if the audience does not merely choose a story, but generates narrative through movement itself?

Through my ongoing research into the theory of Expanded Cinema, I have increasingly realised that a truly immersive moving image experience does not lie in offering audiences more choices, but in fundamentally dissolving the boundaries between viewer and image. Inspired by Claire Bishop’s writings on participatory art (Bishop, 2012) and practices such as teamLab’s spatial installations, I posed a fundamental question: what if the audience does not merely choose a story, but generates narrative through movement itself?

This line of thought led to the development of my current curatorial project: a generative installation where audiences actively edit and activate moving images through bodily gestures in real time.

From Theory to Practice: Embodying the Logic of Expanded Cinema

In developing the curatorial framework, I intentionally rejected button-based interactivity — like that of Bandersnatch — which merely shifts control while maintaining a centralised narrative logic. Instead, I proposed a model where the audience’s body movements become the initiating force of cinematic language.

In this installation, Expanded Cinema is not simply about technological expansion but becomes a methodology:

-

Decentralised storytelling;

-

De-structured viewing processes;

-

Open-ended narrative experiences.

The space becomes an editing suite, and the audience becomes the real-time director, using their bodies as tools of cinematic language.

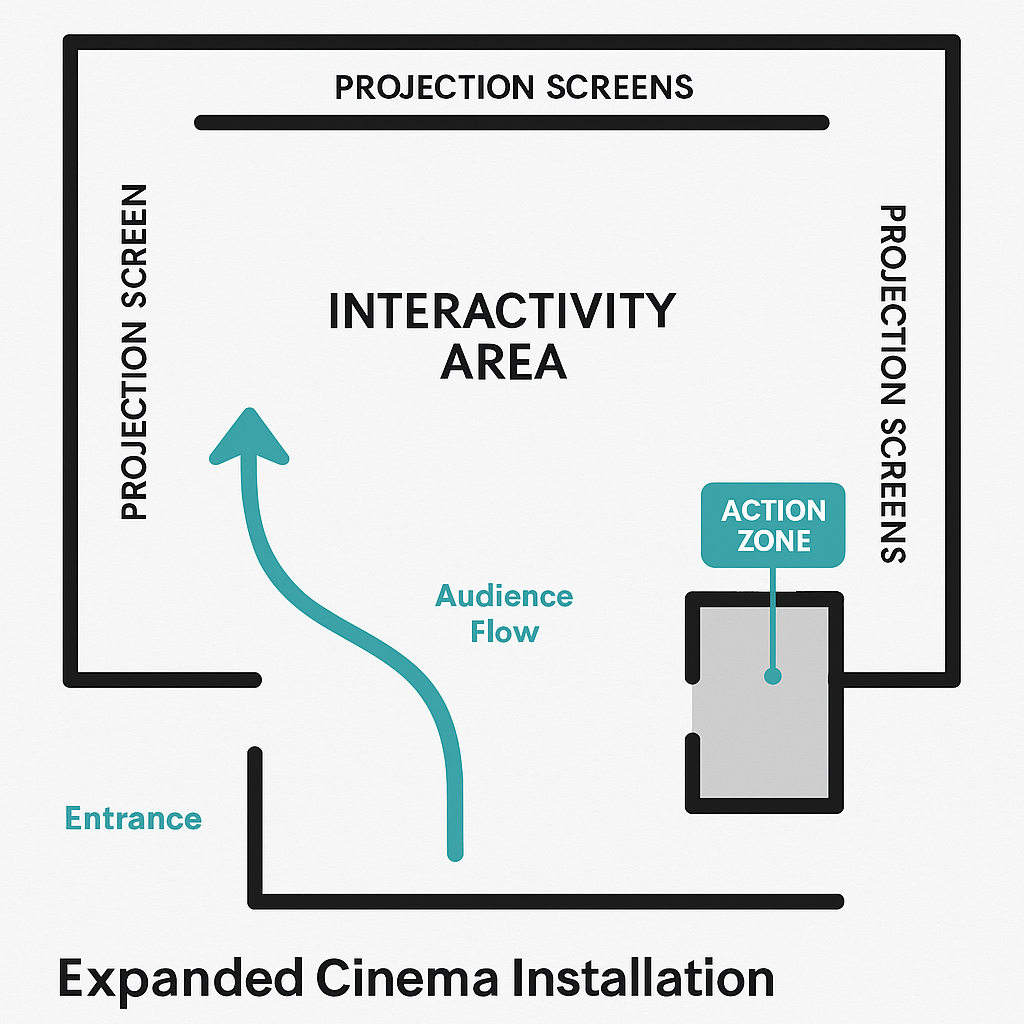

Project Concept and Installation Design

| Theoretical Dimension | Practical Realisation |

|---|---|

| Expanded Cinema | Space as cinema, body as editing suite, movement as cinematic syntax |

| Audience Agency | Audiences dynamically control and collage moving image flows |

| AI Interaction | Kinect or OpenPose captures and maps gestures into narrative triggers |

| Curator-Audience Relationship | Curator designs a language system; audience generates personal narrative versions |

| Non-verbal Interaction | Interaction based on intuitive movement, not verbal instruction |

| Decentralised Narrative | Each audience encounter generates a unique, non-linear experience |

In summary:

Here, you do not merely watch the film — you become the film.

Technical Implementation

| Technical Layer | Practical Details |

|---|---|

| Motion Capture | Kinect or OpenPose to detect gestures like walking, turning, squatting |

| Trigger Mechanism | Gestures mapped to specific cinematic fragments (e.g., turning = flashback) |

| Real-Time Editing | TouchDesigner or Unity stitches sequences dynamically with overlays and sound |

| Sound Feedback | Surround and directional speakers adapt soundscape to audience movements |

| Immersive Projection | Floor, wall, and sheer screens creating a 360-degree environment |

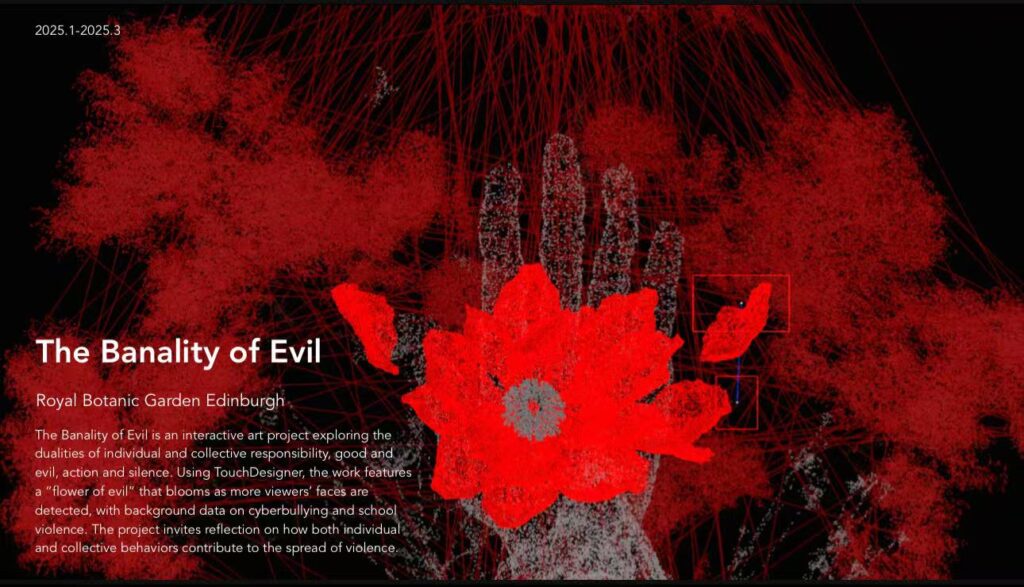

Real-World Inspiration: Encountering The Banality of Evil

During the MA CAT CURATING & MA SITES Workshop in March 2025, I encountered Xudong’s interactive installation The Banality of Evil. This piece used TouchDesigner to track facial recognition data and generated a dynamic ‘evil flower’ that opened and closed in response to the number of viewers present.

What profoundly impressed me was the realisation — through conversations with Xudong — that the project was created under a zero-budget condition.

This encounter solidified two key insights:

-

Powerful narrative experiences do not necessarily require expensive technology;

-

Curatorial success hinges more on narrative precision and experiential design than on technological sophistication.

This real-world example greatly encouraged me to pursue a lightweight, minimalist technical solution for my Expanded Cinema project while maintaining conceptual complexity.

Theoretical Connection: This Week’s Lecture and Contemporary Curatorial Thought

In Marcus Jack’s lecture Media and Time this week, we explored how Expanded Cinema differs fundamentally from traditional screen-based narratives. Expanded Cinema, as discussed, introduces spatial narrative and demands the activation of the spectator within a dynamic environment (Jack, 2025).

This directly resonates with my curatorial model:

-

Audiences do not passively sit within a cinematic black box;

-

Instead, through bodily movement, pauses, and gestures, they edit their own moving image experience in real time.

Thus, the role of the curator shifts — from being the storyteller to becoming the architect of a narrative language environment.

This Week’s Extended Theoretical Reflection: Spectacle and Simulacra

Additionally, through this week’s independent research, I engaged with Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle (Debord, 1967) and Jean Baudrillard’s writings on simulacra (Baudrillard, 1981).

Debord argues that modern society is saturated with “spectacles” where mediated images replace genuine social relations. Baudrillard extends this by proposing that reality itself becomes layered with simulations, leaving us only able to interact with hyperreal “copies” rather than any authentic real.

In reflecting upon my project:

✅ Although the installation generates new spectacles through audience movement, these spectacles are not passively consumed but actively generated.

✅ The moving images are transient, fluid, and incomplete — they form personalised simulacra created through individual bodily presence.

As I describe in the project statement:

“Facing the layered realities described by Debord and Baudrillard, this project seeks to break the traditional one-way relationship between image and viewer, allowing the ‘spectacle’ to emerge through action, and remain permanently unfinished and in flux.”

Conclusion

By combining Expanded Cinema theory, spatial narrative strategies, bodily activation, and critical reflections on spectacle and simulacra, this project aims to create a truly generative moving image environment.

Curation, here, is no longer about constructing a finished story but about building a living language system — one where audiences themselves become the authors of their moving image experiences.

References

-

Baudrillard, J. (1981) Simulacra and Simulation. Paris: Éditions Galilée.

-

Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing. London: BBC and Penguin Books.

-

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

-

Debord, G. (1967) The Society of the Spectacle. Paris: Buchet-Chastel.

-

Jack, M. (2025) Media and Time Lecture, MA Contemporary Art Theory: Curating, University of Edinburgh.