Introduction: Expanded Cinema as a Curatorial Inquiry

This week, my curatorial exploration of Expanded Cinema was further developed through discussions on exhibition-making, curatorial ethics, and peer review. Engaging with James Clegg’s workshop, I began considering the practical and logistical challenges of presenting an interactive, participatory film exhibition. Meanwhile, Dr. Gabrielle Barkess-Kerr’s lecture on curatorial ethics prompted me to reflect on audience agency, power structures, and the ethical considerations of participatory curation.

Rather than focusing solely on the technical aspects of Expanded Cinema, I am increasingly drawn to the ethical implications of audience participation. How much control should curators relinquish in an interactive cinematic experience? What are the limitations of participatory curation, and how do we balance artistic intent with audience agency?

A relevant example is Tate Exchange’s “Who Are We?” project, which blurred the boundaries between curator and audience. This participatory exhibition invited viewers to engage in storytelling and co-creation, effectively shifting curatorial authority towards the public. This resonates with the challenges of Expanded Cinema—when curators introduce participatory elements, to what extent should they relinquish control? How do we ensure that audience contributions enhance rather than disrupt the coherence of the exhibition?

Project Overview: Who Are We?

“Who Are We?” is a participatory curatorial project at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, exploring themes of identity, belonging, migration, and citizenship. Bringing together artists, scholars, activists, and the public, the project uses visual arts, film, photography, design, architecture, and performance to examine the intersection of curation and social issues.

Challenging traditional curatorial models, the project encourages audience co-creation, transforming curation into an open dialogue through interactive installations, workshops, and live performances.

🎥 Video Overview: https://youtu.be/a49O7zwF0Xk

This week’s discussions and readings have led me to reflect on the delicate balance between immersive curation and structured authorship, as well as how participatory Expanded Cinema can maintain curatorial integrity while providing audiences with a truly meaningful interactive experience. This may be the key issue that my project should explore in greater depth.

Balancing Curatorial Structure and Audience Agency

The exhibition-making workshop with James Clegg provided practical insights into the logistics of curating.

A relevant example is Punchdrunk’s immersive theatre, which challenges traditional audience passivity. In Sleep No More, audience members freely navigate the performance space, choosing which scenes to engage with and even interacting with performers. This model raises crucial questions for Expanded Cinema:

- Does increased audience agency redefine cinematic authorship?

- Should curators set boundaries for participation to maintain artistic coherence?

Like Punchdrunk’s approach, Expanded Cinema demands an ethical reflection on audience agency—where does participation enhance the cinematic experience, and where does it risk fragmenting it? These considerations will be central as I refine my speculative project.

Refining the Expanded Cinema Exhibition Model

From peer discussions and faculty feedback, I realized the need to refine my curatorial model. Initially, I proposed three components. However, after further reflection, I am considering streamlining the structure to focus on:

✅ Immersive Expanded Cinema – Films that evolve through interactive audience choices.

-

Theoretical Framework: Audience Agency & Participatory Curating

The concept of audience agency is central to participatory curating, which is particularly relevant in the Expanded Cinema model. Claire Bishop (2012) states that “participatory art challenges the traditional curator-artist-audience hierarchy by redistributing creative control” (Bishop, 2012). In Artificial Hells, she critiques participatory art’s utopian promise, questioning “whether audience involvement genuinely democratizes art or merely serves as a curatorial illusion of inclusivity” (Bishop, 2012). This tension is critical in Expanded Cinema, where interactivity can empower audiences but also pose ethical dilemmas regarding curatorial control.

-

Case Study: The Factory of the Sun (Hito Steyerl) – Interactive Media & Curatorial Control

🌐Reference website:

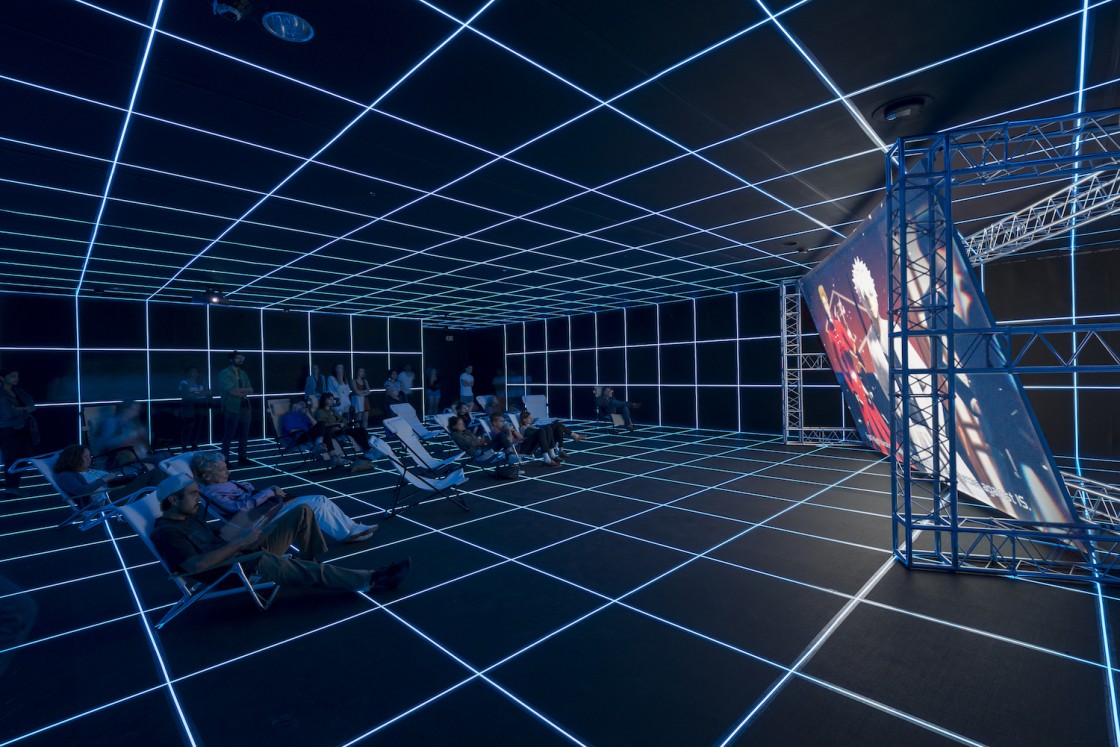

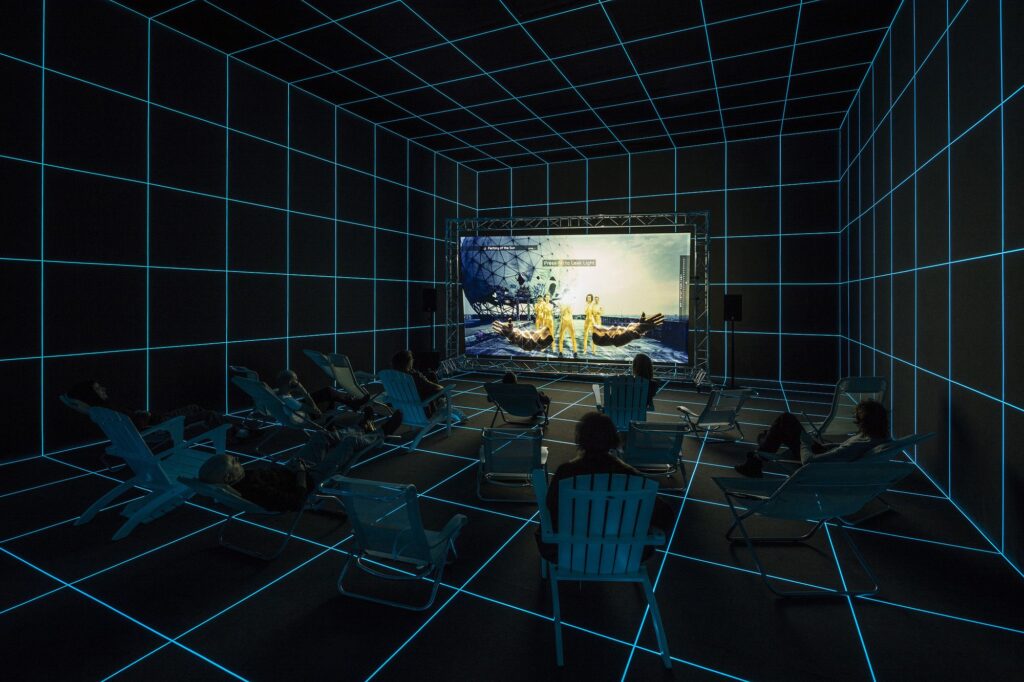

A compelling example of Expanded Cinema’s intersection with interactive media is Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun (2015), an immersive video installation that blends gaming aesthetics, political critique, and digital culture. Originally presented at the German Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, the installation places the audience in a futuristic motion-capture studio, where they navigate a hypermediated space of surveillance, resistance, and digital capitalism.Unlike traditional film screenings, Factory of the Sun blurs the boundaries between passive spectatorship and interactive participation.

Expanded Cinema dismantles the rigid structures of traditional curation by integrating audience interaction and digital technology. Similar to Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun, where participants navigate a hyperreal environment, curators of interactive film exhibitions must confront the paradox of control and openness. If audiences dictate the cinematic experience, how do curators maintain the integrity of their vision without restricting creative participation?

In reevaluating the curatorial model for Expanded Cinema, I have recognized the necessity of balancing audience participation with curatorial control. As Smith (2017) states, “Curating is not merely about displaying artworks; it is a mode of knowledge production” (Smith, 2017). However, excessive audience participation may blur curatorial intent and weaken the coherence of the exhibition. Therefore, curators must carefully design interactive elements to ensure that audience engagement enhances the exhibition experience without diverting from its core curatorial vision.

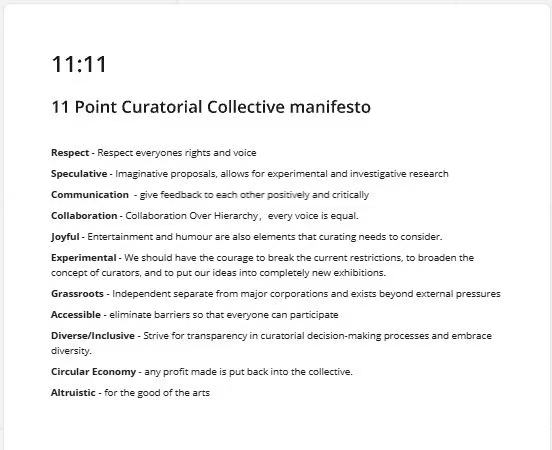

Integrating the Curatorial Collective Manifesto into Expanded Cinema

The 11-Point Curatorial Collective Manifesto provides a framework for ethical, inclusive, and experimental curatorial practices. It emphasizes non-hierarchical collaboration, accessibility, and speculation, which directly inform my Expanded Cinema project. By aligning my curatorial approach with these principles, I aim to develop a participatory exhibition model that rethinks audience agency and curatorial control.

Balancing Curatorial Control & Audience Agency

A key challenge in Expanded Cinema is determining how much control curators should relinquish to audiences. The manifesto’s emphasis on collaboration over hierarchy suggests that audiences should play an active role in shaping the cinematic experience. However, as Bishop (2012) argues, participatory practices often present a curatorial paradox—while they claim to empower audiences, they may still reinforce existing power structures (Bishop, 2012). This tension requires careful navigation in my project, ensuring that interaction remains meaningful without compromising the curatorial vision.

Experimentation & Ethical Curation

The manifesto’s commitment to experimental curation aligns with my project’s goal of rethinking traditional exhibition formats. Expanded Cinema challenges passive spectatorship, allowing viewers to actively shape the narrative. However, Steyerl (2015) warns that digital interactivity can also serve as a tool of control, as media environments often dictate user behavior under the guise of participation (Steyerl, 2015). This raises ethical questions—how much agency is truly given to the audience, and how much is predetermined by the curatorial structure?

Sustainability & Community Engagement

The circular economy principle of the manifesto inspires me to consider sustainable exhibition models. Instead of one-time installations, my Expanded Cinema project could explore modular, adaptable formats that allow for ongoing community engagement. As Finkelpearl (2013) suggests, participatory art should not only engage audiences but also foster long-term cultural production beyond the confines of a single exhibition (Finkelpearl, 2013). This perspective encourages me to design an exhibition that extends its impact beyond the initial experience, perhaps through open-source digital archives or interactive community screenings.

The 11-Point Manifesto serves as a guiding philosophy for my Expanded Cinema project, ensuring that it remains both innovative in form and ethically sound in execution. By critically reflecting on audience participation, ethical interactivity, and sustainable exhibition design, I am developing a curatorial model that challenges traditional cinematic experiences while remaining socially responsible and inclusive.

Conclusion: Moving Towards an Ethical and Feasible Model

Expanded Cinema challenges conventional curatorial hierarchies, raising questions about audience agency, artistic intent, and curatorial ethics. As I refine this project, I aim to find a balance between immersive participation and structured curation, ensuring an experience that is both engaging and ethically responsible.

references:

1. Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial hells : participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. London: Verso.

2. Smith, T. (Terry E. ) & Independent Curators International. (2012) Thinking contemporary curating. New York: Independent Curators International.

3. Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

4. Steyerl, H. (2015) Duty-Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War. London: Verso.

5. Finkelpearl, T. (2013) What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation. Durham: Duke University Press.