Exploring GOMA: Curatorial Reflections and Inspirations

Visiting GOMA in Glasgow was an immersive experience that deepened my understanding of contemporary curatorial approaches. I am primarily interested in exploring the gallery 4 – ‘Domestic Bliss’ exhibition and in conjunction with the curatorial interviews, I have gained new insights into curatorial practice, spatial design and audience interaction. The exhibition not only showcases artworks, but also speaks to the deeper social issues behind family life through socio-historical objects, installations and spatial arrangements.

1. Narrative and Space: Blurring the Boundaries

One of the most striking aspects of the exhibition was the interplay between two- and three-dimensional elements. Several of the artworks below cleverly use black line drawings on the walls, extending the physical part of the artwork into the gallery space. For example, only the outline of the fireplace and sink are drawn on the wall, while the exhibits (such as photographs, sculptures, or installations) are placed in these ‘domestic’ environments. This design allows the viewer to visualise and fill in the ‘missing pieces’, thus making the domestic space open and inclusive. This approach effectively blurs the boundaries between artwork and space, and I found this technique particularly compelling in engaging the viewer in immersive storytelling.

From a curatorial perspective, this challenges traditional methods of display. Rather than treating artworks as isolated objects, this approach integrates them into the surrounding architecture, encouraging a more interactive and interpretive experience. In my own curatorial work, and particularly in my exhibition The Second Skin, I have been exploring ways of creating non-linear, immersive experiences. The way in which this exhibition expands physical and conceptual boundaries reaffirms my interest in multi-dimensional narratives, where the artwork doesn’t just ‘occupy’ the space, but ‘transforms’ it.

2. Audience Interaction: From Individual Experience to Collective Memory

In the interview, the curator mentioned that the exhibition hopes to trigger the audience’s memories of their own ‘homes’ rather than just looking at the artefacts. For example, some of the exhibits are taken directly from the daily objects of ordinary families, and the curators encourage the audience to think about ‘whether a certain object in your home also carries a certain social history?’ This kind of curatorial thinking not only focuses on individual experiences, but also makes connections to the wider social context.

When curating an exhibition, I can also invite visitors to contribute their own objects, photographs or stories to make the exhibition more open. For example, in ‘The Second Skin’, could I ask visitors to upload a photo of the most memorable piece of women’s clothing in their home and write down their memories related to this piece of clothing? These personal stories can be used as part of the exhibition to build a ‘social memory archive’ with the participation of the audience.

3. Curatorial Ethics: How to Deal with Colonial History and Family Themes

In the interviews, the curators mentioned that they had to delicately deal with Glasgow’s colonial history in the exhibition, and in particular the history of the building that houses GoMA itself. There is a certain historical irony in the fact that the building was once owned by slave traders and is now being used for an exhibition about ‘family’. Through the works and texts, the curators hope to suggest to the viewer that what we understand as ‘domestic comfort’ today may be based on the injustices of the past.

This reminds me of the need to be careful about the perspective of historical narratives when curating any exhibition that deals with social history. For example, when discussing the evolution of women’s clothing in The Second Skin, I also needed to consider how the standards of what we consider ‘feminine beauty’ today have been shaped by history, politics and power relations. In the curatorial text, I can bring in narratives from different perspectives, including historians’ research, feminist theories, and even oral histories of ordinary people, rather than just the dominant narrative.

4. Symbolism and Social Commentary

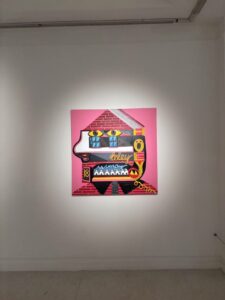

Two vibrant graphic works are shown below, set against a pink background. Filled with layered symbols—eyes, faces, geometric shapes—these paintings evoke dreamlike or subconscious narratives, emphasizing the psychological depth of the images. These works inspired me to think about how to effectively use symbolism to curate thematic exhibitions. Rather than relying solely on explanatory text, it is better to engage the audience with the symbols and visual language, opening up space for multiple interpretations.

In the Sleepwalker curatorial group, if an exhibition is to remain inclusive and dynamic, it should encourage the audience to derive personal meaning rather than passively accept predetermined messages. These paintings reminded me that visual storytelling can transcend textual narratives and trigger intuitive and emotional responses.

Summary: The core of curation is to tell ‘bigger’ stories.

Through the curatorial interviews and set-up of Domestic Bliss, I learnt a lot about how curation can go beyond traditional display and become a narrative device.

✨ Key Inspiration:

✅ Curating is not just about exhibiting artefacts, it’s about constructing narratives – richer contexts can be constructed through historical objects, archives, personal stories and so on.

✅ Space can be ‘imagined’ – moving away from the rigid gallery format through lines, installations or open scenes can transform exhibitions into more immersive environments, allowing the audience to complete their own experience.

✅ The audience is part of the curation – through interactive mechanisms, the exhibition becomes part of the collective memory.

✅ Curating has a social responsibility — when dealing with historical and social issues, consider how to present the content in a multi-faceted and responsible way.

✅ Layered Symbolism and Open Interpretation – Encouraging personal engagement through visual metaphors rather than over-interpreting the subject matter can make an exhibition more dynamic.

In my future curatorial practice, I would like to draw more on these strategies, so that the exhibition is not just a collection of works, but a constantly flowing space that can be re-written by the audience.

References:

Devine, T.M. The Scottish Clearances: A Distory of the Dispossessed, 1600 – 1900.

How Glasgow Flourished – Glasgow Museums blog

Legacies of Slavery and Empire in Glasgow Museums’ collections blog

Exploring GOMA: Curatorial Reflections and Inspirations / Hua Ding / Curating (2024-2025)[SEM2] by is licensed under a

Exploring GOMA: Curatorial Reflections and Inspirations / Hua Ding / Curating (2024-2025)[SEM2] by is licensed under a